Jenny Carla Moran is a Postcolonial studies MA student at SOAS University of London. She is the co-founder and a previous co-head editor of Trinity College Dublin’s feminist journal, nemesis. Her current research interests include post-structuralism, gender theory, and embodiment in the digital age. Her perpetual interests include circles of femme friendships and cats.”

Defining “world literature” means drawing boundaries. These boundaries dictate what is seen as legitimate, valuable, and worth analysing. Foucault describes this partitioning as defining “compact hierarchical networks” (220). [1] In other words, the formations of networks which we call “disciplines” are inextricably bound to power relations. What we study, and how we study it, therefore, plays a fundamental role in the production of discourses of knowledge and power. The Mulosige project recognises this, and has therefore sought to challenge the forms, periods, and locations considered when we talk about world literature. I propose we take this problem of form forward by taking our original question backward: What do we define as “Literature” in the first place? [2]

It is important, firstly, to contextualise this question. As a postcolonial scholar, I consider Literature from a particular position, which it may do well to briefly explain. With regard to power hierarchies, the discipline of postcolonial studies addresses forms of communication and documentation both from the bottom up (Subaltern Studies scholars, such as Gayatri Spivak, have sought to extract the voices lost in the imperial process of history-making) [3] and the top down (one of the founding theorists of postcolonial studies, Edward Said, analyses Western Literary texts to examine the creation of the racialised Other). [4] Fundamental to both reading from the bottom up and the top down is the problematic of representation: those who cannot speak are written over; those who can speak cannot interpret, strategically misrepresent, or indeed dehumanise the subjects about whom they write. It follows, therefore, that theorists such as Said would focus on historical documents, Literature afforded power through legitimation, popular artists, news reporting and framing, etc., when carrying out their analyses. Forms of communication, however, have been fundamentally revolutionised in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, introducing new materials to our studies. We are, therefore, in a very unique position as scholars, because the founding theories of our relatively-new school already require stretching to adapt to a new age of representation, in which questions of communication and access are being constantly renegotiated: the digital age.

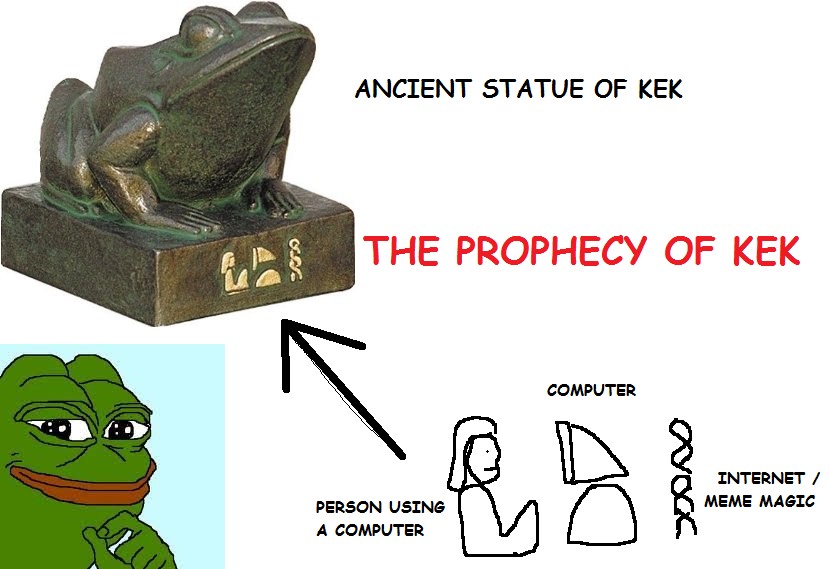

An example of the use of a Pepe the Frog meme made by a self-proclaimed members of the internet nation of “Kekistan,” a country invented by users on 4chan’s /pol/ board as the tongue-in-cheek ethnic origin of alt-right “shitposters,” known as “Kekistanis.” (via Wikimedia Commons)

This brings me to my titular rhetorical question: “What’s in a Meme?” It may, at first, seem laughable to propose something like studying white supremacy through Pepe the Frog within a discipline which has historically taken on works afforded such acclaim as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. [5] We cannot, however, allow the fixity of boundaries drawn between disciplines to skew our research. While it is undeniable that texts such as Conrad’s speak to and have shaped the white racial imaginary in relation to the Other, it is also true that digital media affect most people’s knowledge of and interaction with one another. Global internet penetration rates, for example, show that 51% of the world’s population use the internet in 2017. To ignore the influence of online communication, language, images, videos, resources, blog posts, forums, etc., which are immediately accessible to this digitally-literate population, would be to discount some of their primary daily engagements with representation. If scholars are to understand contemporary constructions of identity, in other words, we must engage in interdisciplinary research.

“Samantha,” a sex bot designed by Dr Sergi Santos as an objectified embodiment of femininity which submits to its user’s sexual desires (Ars Electronica via Flickr).

Without interdisciplinarity, limitations to the work we can produce become clear. If postcolonial scholars study Literature (taken here as novels, maybe some poetry), media scholars study digital communications, feminist theorists study gender, computer scientists learn code, etc., in what academic space might the possibility of analysing something as unfounded and as pressing as the creation of racialised rape bots exist? How might new modes of Digital Blackface be understood? What kinds of collaborations would be required to investigate online imagined Black English? Are these not clear examples of constructions and representations of the Other that will fundamentally affect the founding theories of postcolonial studies forever? And how, too, might we theorise spaces of resistance online? [6] Who would be able to analyse collaborative Twitter novels? [7] Does digital agency not give some silenced people the platform to write back in ways which may affect subalternity? [8] And what does this mean, then, for the digitally illiterate? Taking these questions that arise from my particular academic perspective as an example, I argue that we simply cannot hope to keep up with renegotiations of identity and representation in the digital age without similarly renegotiating our own approaches.

It is for this reason that we must reconsider what we mean by “Literature”. By destabilising the fixity of this category, for example to include online language and communications – as well as forms of writing not as popularly recognised in academia, periods not as frequently studied, and authors eclipsed by eurocentrism – we might understand representation and embodiment in entirely new ways. Destabilising our definition of Literature in turn destabilises the category of world literature. Recognising online language and communications in cyberspace would shift our focus to how people communicate with one another as digital agents frequently able to contact and access one another, as opposed to focusing on Literary communications as mediated by publicists, economics, and global power relations. This shift could therefore reflect the new ways in which members of the world come to know, define, and write each other.

Notes:

[1] Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish. Trans. Alan Sheridan. 3rd Ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1991.

[2] I use “Literature” here as opposed to “literature” to denote forms of writing more typically recognised in academic departments.

[3] See, for example: Spivak, Gayatri. Can the Subaltern Speak? Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988.

[4] See, for example: Said, Edward. “Introduction.” Orientalism. New York: Random House, 1979.

[5] See, for example: Achebe, Chinua. “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.” Hopes and Impediments. Oxford: Heinemann, 1988.

[6] See, for example, Cunningham’s theory on media sphericules as subaltern counterpublics: Cunningham, Stuart. “Popular media as public ‘sphericules’ for diasporic communities.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 2001, pp. 131-147.

[7] See, for example, this collaborative twitter novel by Teju Cole.

[8] See, for example: Gajjala, Radhika. “Introduction.” Cyberculture and the Subaltern. Maryland: Lexington Books, 2013.

Abreu, Manuel Arturo. “Online Imagined Black English”. Arachne, Fall 2015. arachne.cc/issues/01/online-imagined_manuel-arturo-abreu.html Accessed 14 Dec. 2017.

Achebe, Chinua. “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.” Hopes and Impediments. Oxford: Heinemann, 1988.

Archer, Angel. “Botline Bling.” Real Life, 14 Sep. 2016. http://reallifemag.com/botline-bling/. Accessed 15 Dec 2017.

Clift, Jack. “‘What isn’t World Literature?’ David Damrosch and the IWL.” MULOSIGE, 7 Aug. 2017. http://mulosige.soas.ac.uk/damrosch-institute-world-literature/. Accessed 15 Dec 2017.

Cole, Teju. “Hafiz.” Twitter, 8 Jan. 2014. https://twitter.com/tejucole/timelines/437242785591078912. Accessed 15 Dec. 2017.

Conrad, Joseph. “Heart of Darkness”. Blackwood’s Magazine, vol. 165, no. 2-4, 1899, pp. pp.193-220, 479-502, 634-57.

Cunningham, Stuart. “Popular media as public ‘sphericules’ for diasporic communities.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 2001, pp. 131-147.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish. Trans. Alan Sheridan. 3rd Ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1991.

Gajjala, Radhika. “Introduction.” Cyberculture and the Subaltern. Maryland: Lexington Books, 2013.

Jackson, Lauren Michele. “We Need to Talk about Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs.” Teen Vogue, 2 Aug. 2017. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/digital-blackface-reaction-gifs. Accessed 15 Dec. 2017.

Said, Edward. “Introduction.” Orientalism. New York: Random House, 1979.

Spivak, Gayatri. Can the Subaltern Speak? Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988.

Leave A Comment