In the second installment of our series on concrete poetry, MULOSIGE’s Jack Clift speaks to Danish poet and artist Morten Søndergaard about his latest work, Wall of Dreams, which was on display at London’s Southbank Centre from 19 October to 1 November 2017. A selection of images of this and others of Søndergaard’s works is included at the bottom of this article. Read July Blalack’s introduction to concrete poetry for MULOSIGE.

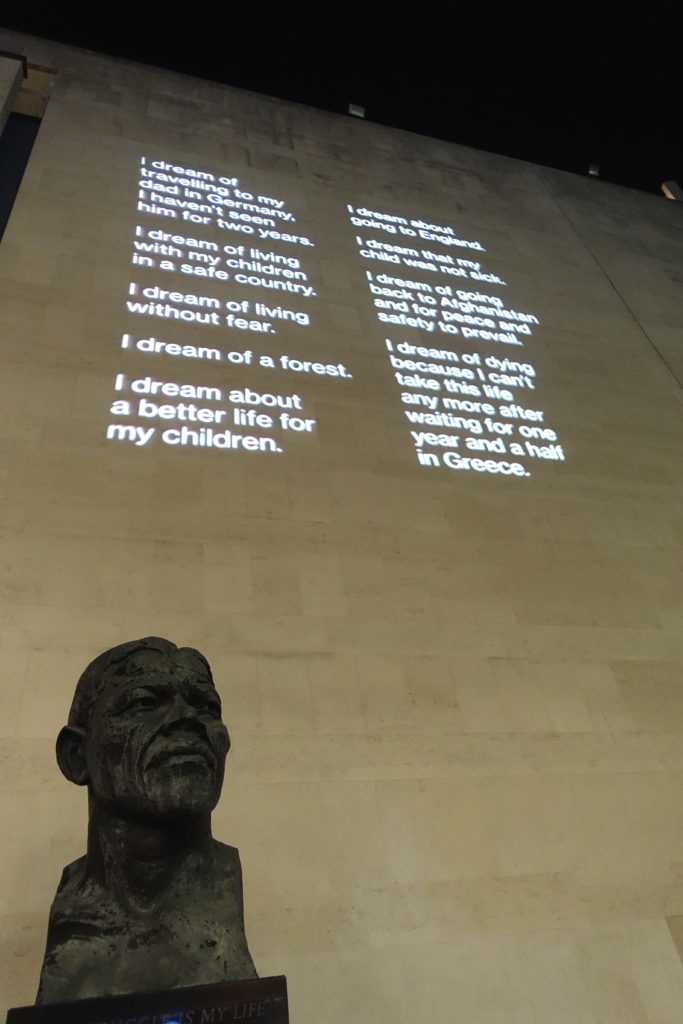

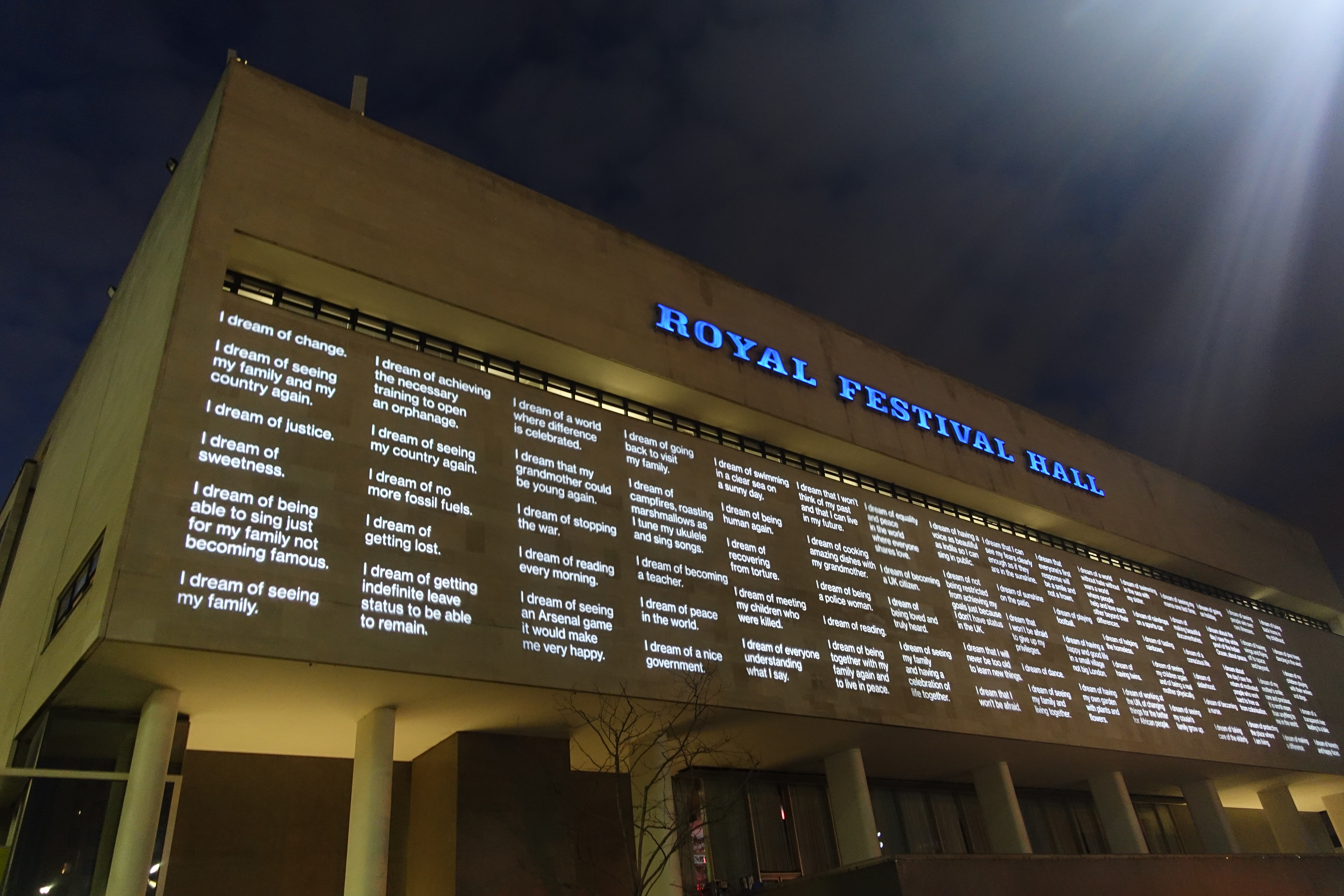

Part of Morten Søndergaard’s Wall of Dreams (2017) above a bronze bust of Nelson Mandela

It is a brisk October evening when I meet Danish poet and artist Morten Søndergaard outside London’s Royal Festival Hall. Above our heads – and that of a bust of Nelson Mandela – is Søndergaard’s latest work. Projected in crisp white light onto the building’s concrete façade are a number of simple sentences. All of them start with the words, ‘I dream.’ And all of them were spoken by one of over 600 refugees with whom Søndergaard worked to create his Wall of Dreams installation.

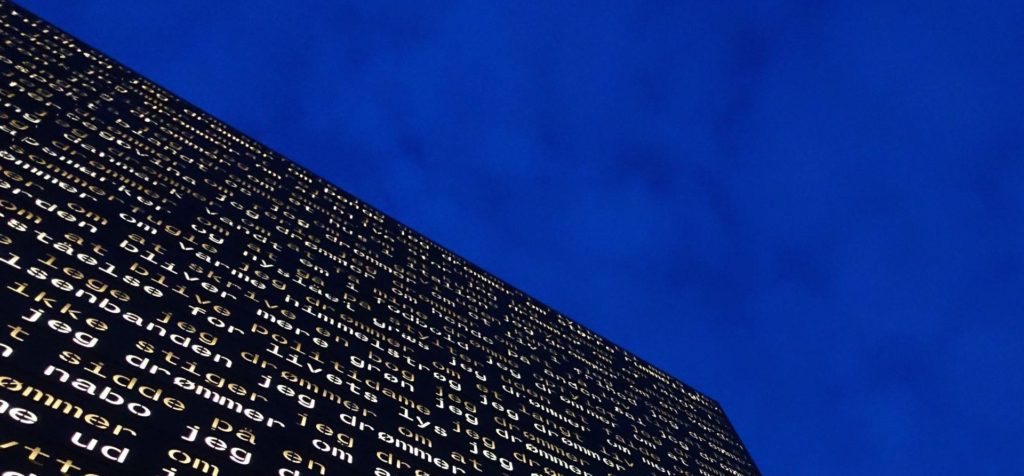

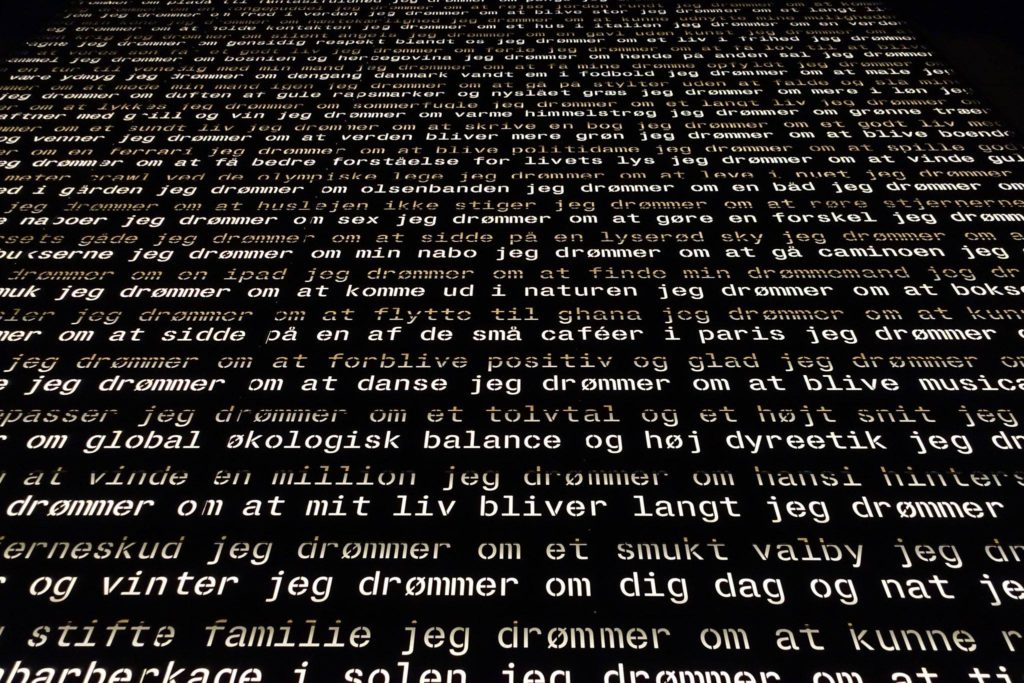

Wall of Dreams is part of the annual London Literature Festival and the Southbank Centre’s year-long Nordic Matters series, events focussing on the art and culture of the UK’s Nordic neighbours. The installation has a longer history for Søndergaard, though. The poet first experimented with public art on this scale in his work Drømmegavlen (‘The Dream Gable,’ 2015), which brought together the dreams of 117 residents of the Copenhagen suburb of Valby. With the help of a 600m2 sheet of LED lights, the inhabitants’ dreams now shine out from the end of their housing block in Gadekærvej, the focal point of the neighbourhood’s small public square. The inspiration for Drømmegavlen came, in part, from the intricacies of art that has for thousands of years made use of the Perso-Arabic script. The words here take on a similarly ornate and ethereal form, even if the content contained within them is oftentimes more personal. But for Søndergaard there was also something of an ethical question at the centre of the work. Commissioned as part of the redevelopment of the building and the surrounding area to better serve the occupants’ needs, Søndergaard felt that imposing his own words on public art meant for the enjoyment of others would deprive the residents a voice in their own community.

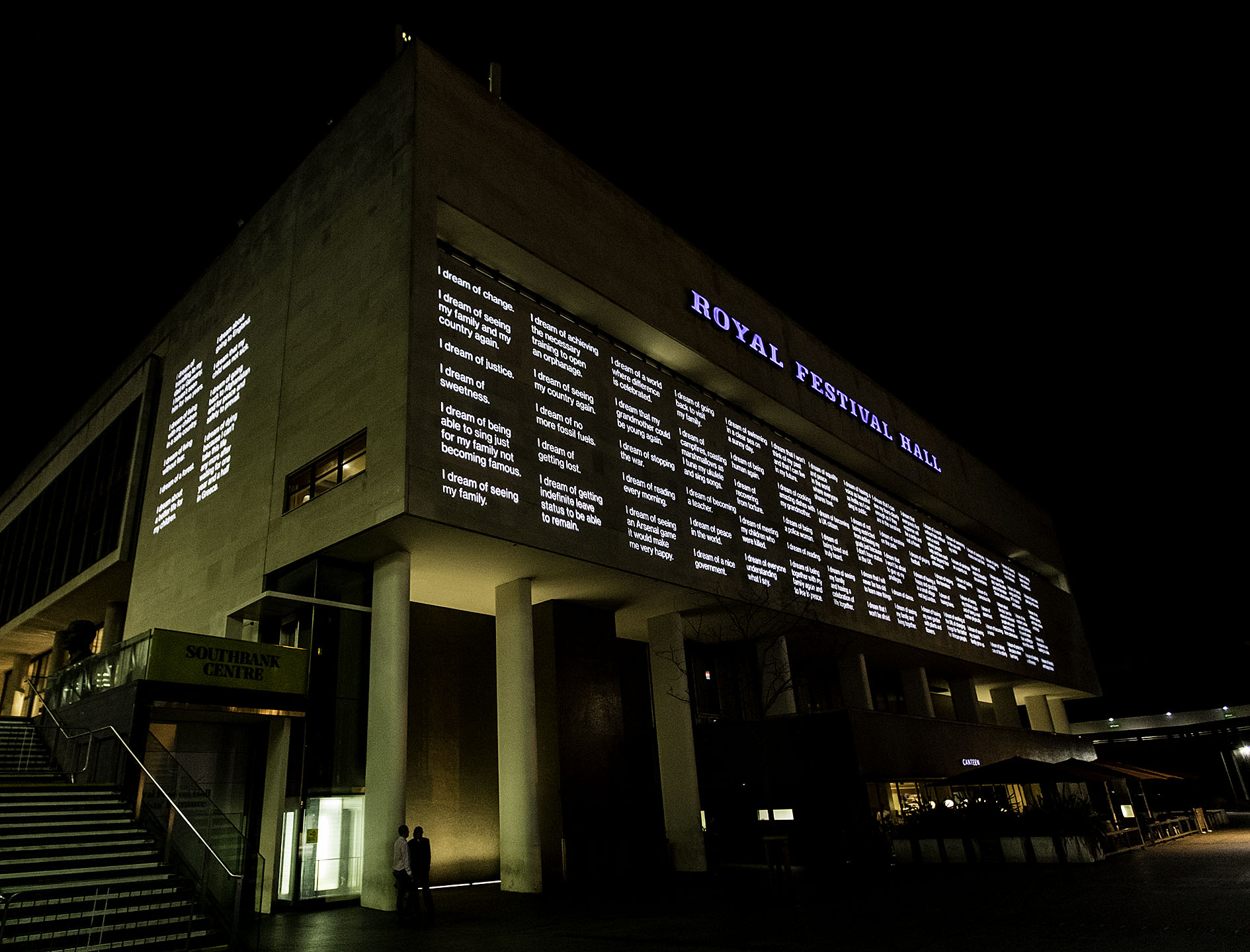

This sentiment has carried over to the Wall of Dreams, which Søndergaard describes as a ‘mirror project’ to Drømmegavlen. The dreams that are projected every night onto the walls of the Royal Festival Hall are not those of Søndergaard, nor of the poets Jasmine Ann Cooray and Kayo Chingonyi with whom he collaborated in the project. They are the dreams, aspirations and hopes of hundreds of refugees in Italy, France and the United Kingdom, as well as 250 dreams collected in Greece with the help of the Danish volunteer worker Naja Ashley Misfeldt. They range from the heart-rending (‘I dream of dying because I can’t take this life anymore’), to the humbling (‘I dream of happiness in your life’), with a fair dose of humour in between (‘I dream of meeting the rest of One Direction’). And, as Søndergaard tells me in a bar that overlooks the projections, they were collected both from interactions with those confined to refugee camps and from meetings of social groups in the refugees’ destination countries. Encounters with refugees in Paris had already pushed Søndergaard to consider expanding his Drømmegavlen project, and a commission from the Southbank – timed to coincide with events at the centre for Poetry International – allowed him to extend the work. In doing so, the voices of those who are so often silenced gain recognition from a broader audience.

Morten Søndergaard’s Drømmegavlen (2015) installation in the Copenhagen suburb of Valby

None of this is lost on Søndergaard. Although still unsure about the exact ramifications of the work, it is clear that there is a statement of political intent bound up in his dream projections. For instance, the printed notes available at the installation, which feature each of the dreams written out in full, come in the shape of a broadsheet newspaper, complete with thin newsprint-esque paper, ink that rubs off slightly on your hands and pinholes along the bottom margin. There is a biting irony to displaying the dreams of refugees in a way that mimics the print media that have, by and large, been instrumental in the vilification of ‘migrants’ and the fostering of xenophobia in the European public sphere, particularly in the UK. Yet this link between the textual and the material is a recurrent theme in Søndergaard’s work, and one which Wall of Dreams takes in exciting new directions. Just as the French term for ‘illegal’ immigrants – les sans-papiers, those ‘without papers’ – forges a connection between holding material paper and possessing figurative or actual rights, so Søndergaard’s piece strives to connect the physical representation of the dreams with their immaterial or conceptual content. This is achieved primarily through the light itself. The light, Søndergaard says, is ‘beautiful yet undestructive,’ a medium of constructive potential that does not deface or scar the surrounding materials. The light allows these dreams – these intangible thoughts that so often evaporate in our first waking moments – to become ‘concreted,’ solidified in a way that makes them visible, if not always understandable, to those who stroll past the Royal Festival Hall. Yet it is precisely in this concreted-ness that we note the dreams’ distinct lack of concreteness. Simultaneously concreted yet not concrete, the dreams are temporary and a fleeting insight into the hopes of those whose voices are so frequently sidelined in public discussions of migration. That the dreams projected rotate every night, and that bottom row of dreams in each set seems to dissolve into the surrounding walls, is a testament to the liminal space they occupy.

Søndergaard’s Wall of Dreams viewed from the southern side of Royal Festival Hall

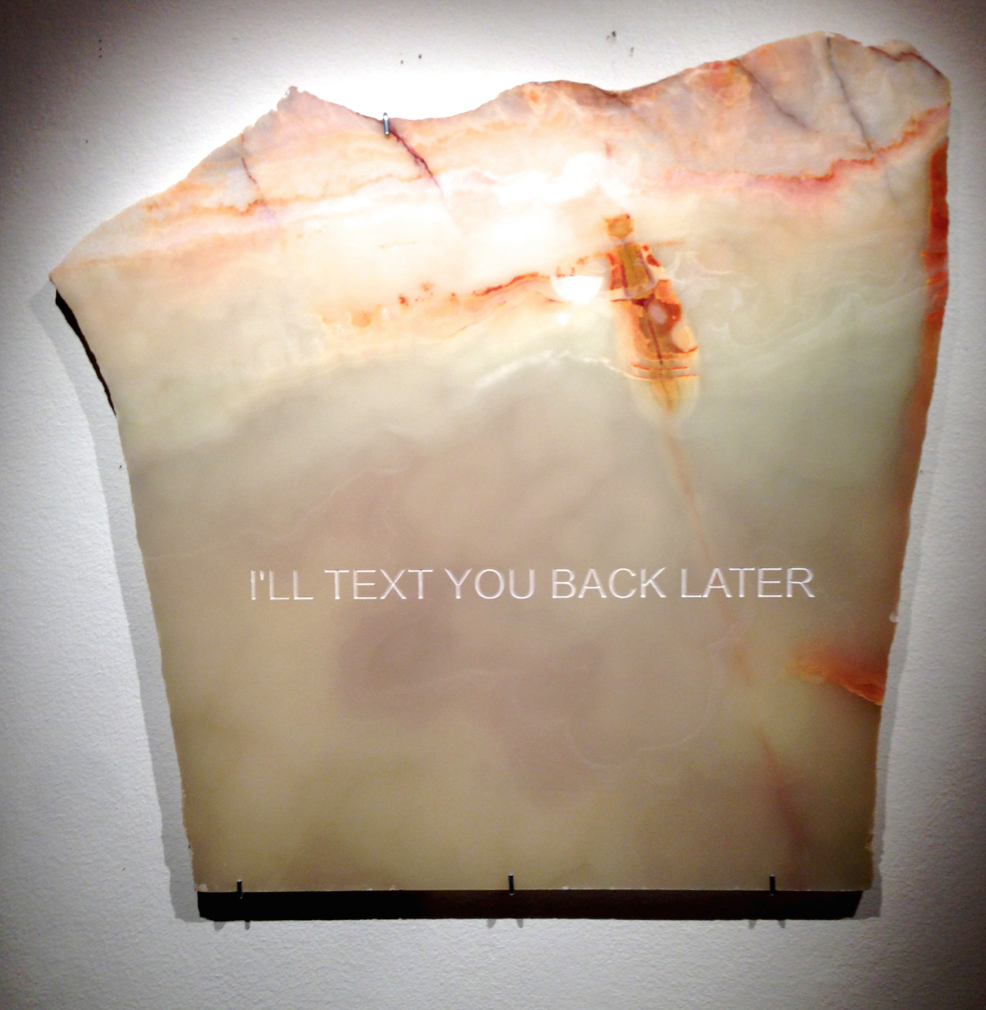

Wall of Dreams is, Søndergaard freely admits, a piece of concrete poetry. The movement has influenced his work for a long time, as his website testifies, and it is within the constraints of such ‘concrete’ visual art forms that the poet finds a hugely productive artistic space. This is notable in a number of Søndergaard’s other works, including the collection of mysterious, sometime broken, objects that made up Bestiarium (2014) and, more recently, in his work in and on marble. As well as carving isolated pieces, marble formed the basis of Ukend dig selv (‘Unknow thyself,’ 2017) at the Brandts 13 museum in the Danish city of Odense. The work – a collaboration in part with his son Sophus Helle, who has written a wonderful reflective piece on Søndergaard’s work – features Danish translations of lines from the Shumma alu, a collection of truncated Babylonian omens that are made up of ‘ifs’ but not ‘thens.’ These have been carved into marble on the floor of the museum’s main hall, prompting visitors to engage in a new form of reading: ‘on my floor,’ Søndergaard writes on his website, ‘you will read with your body and you will read by moving physically into a reading dance. And the reading will leave traces of reading on the floor.’[1] Through the conduit of poetry, the materiality of the art comes face-to-face with the body of the reader.

Notable too in these works is Søndergaard’s interest in language, in both poetic and visual terms. In Ukend dig selv, translations of the Babylonian text made by Helle for Søndergaard provide the core of the work. The Babylonian original is mirrored in the structure of the Danish translation, but the gap between the two languages remains rather large. In Søndergaard’s ongoing project Ordapotek (‘Word Pharmacy,’ 2010), by contrast, the poet dives deep into the different structures of languages themselves, focussing on linguistic building blocks and their categorisations. The work ‘playfully equates the structure of language with pharmaceutical products’ and, in its Danish original, ‘consists of ten medicine boxes, each representing one of the ten different word groups, and each containing a “User Information Leaflet” that typographically resembles the kind of leaflets normally found in medicine boxes,’ in much the same way that the printed notes in Wall of Dreams physically and typographically call to mind real-life newspapers. This focus on the vital minutiae of the language has been successfully exported to a number of different languages, most remarkably Welsh.[2] But, I ask Søndergaard, what about the language of the Wall of Dreams? What role does language – English, in this case – play in structuring the work? The language of the dreams as they are presented is English, but this is not necessarily the languages in which the dreams were had.

I’ll text you back later: Søndergaard’s work on marble

Søndergaard concedes that it is a shame to bring the dreams of the refugees out of their own languages, although many of the dreams collected in refugee camps were originally gathered in the refugees’ first languages and subsequently translated. At the same time, he notes that their rendering in English not only enforces constraint but also introduces ambiguity. Both are, in a sense, productive for the poet. The constraints of language, just like the constraints of materiality in concrete poetry, force the poet to think laterally and present meanings in ways that might otherwise be lost. Simultaneously, the ambiguity inherent in translation allows for a wide array of interpretations to stream forth from these simple phrases. It is this tension between the concreteness and the instability, already introduced by the lights, that makes Wall of Dreams such a fascinating work.

Søndergaard’s interest in language shows no signs of abating. Having developed his Word Pharmacy into an interactive touring piece where visitors can be prescribed remedies to their linguistic ailments from the pharmacy cabinet, Søndergaard is keen to elaborate the idea and bring together a Word or Language Hospital which can examine the connection between language and the body in even more detail. Wall of Dreams, too, has potential for expansion and relocation. Søndergaard admits that he would be particularly gratified to have the projections displayed on Trump Tower in New York – but would perhaps settle for the United Nations building as a statement location

In the meantime, Søndergaard seems happy enough contemplating his work from the nearby bar. The installation’s visibility from this short walkway connecting the Southbank and London Waterloo is no accident. Accustomed to the intense level of visual noise from commercial advertisements in London, many of those hurrying past the installation barely give it a second glance. Others, though, slow down to take it in. Confused, sometimes vexed, expressions soften as the simple gravity of the words hits them. Photographs are taken, and presumably shared. This is the point of this piece, Søndergaard tells me: to challenge people’s assumptions, not only about the refugees whose words are projected on the walls, but about the presence of art in our increasingly privatised public spaces. It seems to be working. As we talk, a passerby, pointing upwards, asks our waiter what the words on the side of the building are there for. ‘It’s about refugees,’ the waiter promptly replies. Søndergaard smiles broadly.

Notes

[1] The Danish here is: ‘Men på mit gulv vil man læse med kroppen og man vil læse ved at bevæge sig fysisk i en læsende dans. Og læsningen vil afsætte læsespor på gulvet.’ The interplay between the process of reading and its physicality is present in the Danish in a way that cannot be rendered precisely in the English: Søndergaard uses the word ‘læsespor,’ a compound of læse (‘reading’) and spor (‘[foot]print,’ ‘track,’ ‘trace’) to mean something like a ‘reading-print.’

[2] Søndergaard comments that when he introduced Word Pharmacy to a Welsh-speaking audience, many of them were taken aback – not by the focus on Welsh, but by seeing an object resembling a medicine box written in the language. Medicine boxes in Wales remain monolingual in English, although recent recommendations from medical and linguistic professionals have called for bilingual English and Welsh labels to be introduced.

To find out more about Søndergaard’s work, visit his website in English or in Danish. You can follow Søndergaard on Twitter (@MoSondergaard) or on Instagram (morten_sondergaard).

Press coverage of Wall of Dreams in the UK has included articles in the Guardian (13 October 2017) and Newsweek (15 October 2017).

This article is the second in a MULOSIGE series on concrete poetry. Read July Blalack’s introduction to the series in full here.

All images courtesy of Morten Søndergaard

Fantastic piece Jack, thank you for exploring so many aspects of Sondergaard’s work so thoroughly. This reminded me of Annie Webster’s post on Blasim, and how he plays with the demand that refugees cultivate a ‘true’ but also ‘correct’ story of their trauma, and how distorting it is to deny them their capacity to imagine while also making their lives depend on telling the right story. In ‘stories as shelter’, Marina Warner responded to the relentless demand that refugees share their ‘true’ stories and their personal traumas over and over in order to ‘prove’ their deservedness, and how this reduces their humanity. For the most part, even very powerful and worthwhile projects to humanize refugees- like Comma Press’ Refugee Tales series- do not focus on refugees’ inner lives or capacity for imagination. The ability to talk about one’s dreams instead of one’s sad reality or past trauma, to still have the space for imagination and dreaming, could be a powerful antidote to this narrative restriction.