This is the part one of MULOSIGE’s series exploring concrete poetry and its implications for our project. The next installment will feature an interview with Danish artist Morten Søndergaard whose concrete poetry piece ‘Word Pharmacy’ inspired similar pieces in other languages, and whose ‘Wall of Dreams’ installation be on display at The Southbank Centre in London from 19 October to 1 November 2017

The saying “don’t judge a book by its cover” succinctly sums up a common view towards the aesthetics of texts – while the appearance is undeniably part of its appeal and can even influence our decision to read it or not read it, it is also inconsequential to its meaning. After all, Hamlet is Hamlet is Hamlet, regardless of whether it is printed in Arial or Times New Roman, and regardless of whether it is packaged as a cheap paperback or in a fine leather-bound edition. However, what if the shape of a text could communicate part of the story, making the words both signifiers of meaning and works of graphic art?

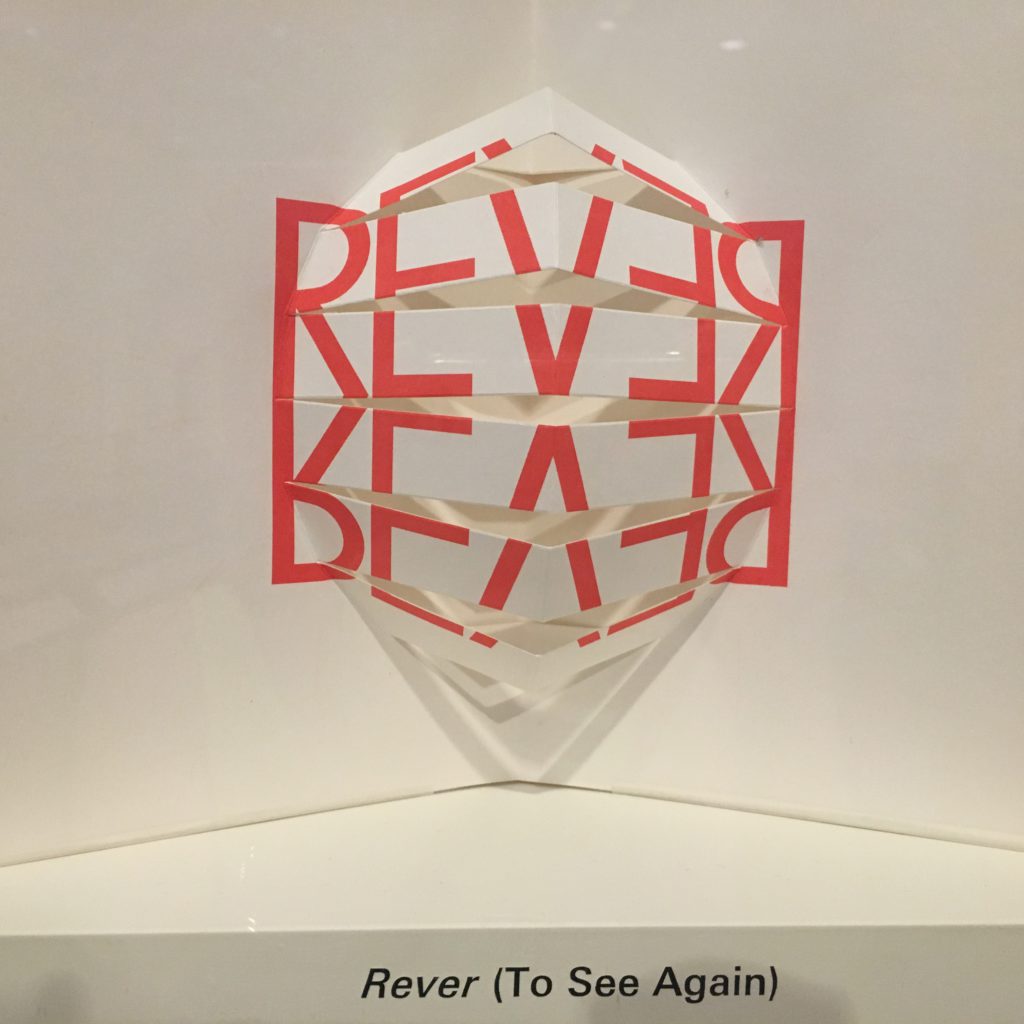

The poemobile ‘Rever’ by Augusto de Campos on display at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Photo by July Blalack.

In the 1950s and 1960s, an art movement with bases in several disparate countries sought to collapse the boundaries between the visual and verbal arts by experimenting with communicating meaning through words’ aesthetics. Almost simultaneously, and apparently without prior coordination, there appeared in Brazil, Sweden, and Switzerland several camps of the Concrete Poetry movement,[1] which then spread to art circles in Germany and Japan as well.[2] Calling their works ‘concrete poems’ alluded to the way the genre makes words’ concrete existence as visual objects matter as much, if not more, than their abstract meanings. There is in fact a wide continuum among concrete poems for how much meaning is derived from the words themselves versus their appearance. There are also concrete poems which use cacophonous layers of voice to draw attention to the sonic element of words independently of their meaning.[3] In all poetry the sound of words and their sounds in relation to each other are an aspect of the art, and so audio concrete poetry could be seen as merely taking this a step further and overemphasizing the audio aspect over the signifying aspect.

Concrete poetry has interesting implications for multilingualism, as it opens up the possibility for speakers of different languages to engage with the same text or poem and, depending on how much of the meaning is derived from the aesthetic qualities of the poem rather than what the words signify, to have semi-overlapping understandings of the piece. Although I do not speak Portuguese, seeing the Poemobile ‘Rever’ by Augusto de Campos (pictured above) gave me the visual experience of seeing something again. As Hilder observes in his study of the movement, the concrete poem “becomes meaningful – though differently meaningful – to readers independent of their national languages.”[4] Haroldo de Campos, one of the founders of the Brazilian Concrete Poetry movement, was also known for his “transcreations”, or translations based on creative misreadings of works in other languages.[5] In this manner, Campos acknowledged that our inner lives may be enriched by texts and poems in languages other than our own, even if we do not comprehend them the way a native speaker would – the words can still be a point of engagement.

“It is certain that words are symbols, but there is no reason why poetry couldn’t be experienced and created on the basis of language as concrete material.”

-Öyvind Fahlström, Manifesto for Concrete Poetry

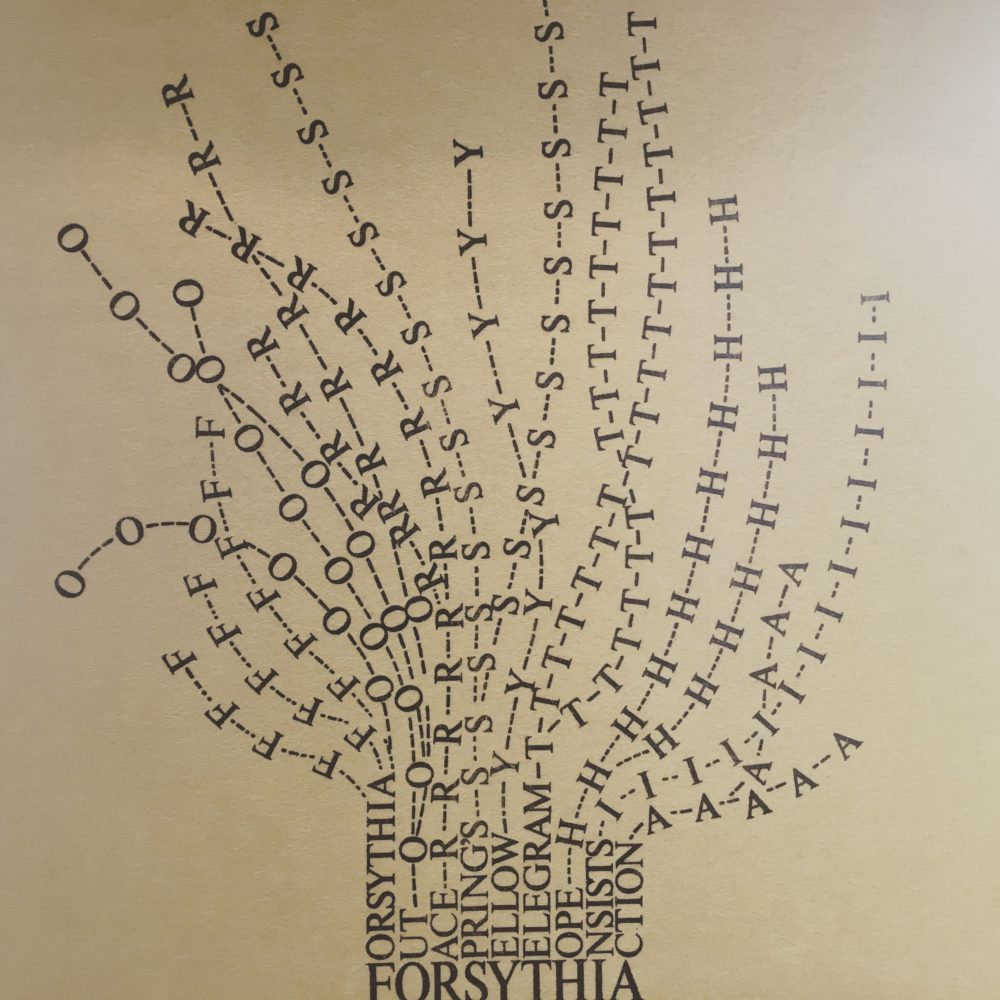

American concrete poet Mary Ellen Solt’s piece ‘Forsythia’ on display at the Getty Museum. Photo by July Blalack.

The Concrete Poetry movement can be seen as one recent manifestation of this engagement with the aesthetics of spoken and written words. Historically, many cultures have revered books as objects of power and magic, and written words have been (and continue to be) used in spells and charms. In the context of rituals, chants transform words from carriers of meaning to to ‘sonic provokers of altered states’.[6] In Sanskrit literature, there is a type of poetry called citrakavya (“figure poetry”) which arranges the words into attractive shapes, and Arabic calligraphy has a long and continuing tradition of bending words into beautiful, flowing shapes, often to ‘draw’ the meaning of the word. Stéphane Mallarmé’s famous poem ‘Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard’ (“A throw of the dice will never abolish chance”, 1897) manipulated white space, font size, and tabulation to emphasize certain words and phrases, and Joyce is famous for inventing words and for playing with their onomatopoeic properties.[7] Even the current trend of English-speakers getting Chinese or Arabic tattoos they would not be able to read or pronounce speaks to the aesthetic pull of words, and how this pull exists independent of their meaning.

Or, perhaps it would be more accurate to say that this aesthetic pull of language is tied into our desire to create meaning, and that this desire does not begin and end with the languages whose abstract meanings we can easily access.

Notes

[1] Small, Irene. “Verbivocovisual: Brazilian Concrete Poetry.” Yale University, publication date unknown. Accessed 10.10.17 at: http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/ciberletras/v17/introjacksonsmall.htm

[2] For more information on the ‘global’ aspect of Concrete Poetry, see Bachner’s article ‘Concretely Global‘ in Globalizing Literary Genres: Literature, History, Modernity.

[3] The Getty Museum of Los Angeles has a digital exhibit with examples of both visual and audio concrete poems

[4] Hilder, Jamie. Designed Words for a Designed World: The International Concrete Poetry Movement, 1955-1971, 2016. Internet resource. (quote from p.4)

[5] Small, ibid.

[6] Green, Nile. Sufism: A Global History. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. Print. (quote from p. 28)

[7] These two examples are also referenced by Small, ibid.

Leave A Comment