Laura Casielles (Spain, 1986) is a PhD student at the Department of Arabic Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Her research focuses on Moroccan authors writing in French and Spanish as well as on writers of the Moroccan diaspora in Spain and France. She has a degree in Journalism, another one in Philosphy and a master in Contemporary Arab and Islamic Studies. She has worked as a journalist in Rabat, and at the moment she is working in the field of political communication and cultural management in Madrid. She is also a poet, and her book «Los idiomas comunes» was awarded with the National Prize for Young Poetry by the Spanish Ministry of Culture in 2011.Laura blogs at trespiesdelgato.com

This article was originally written in Spanish and translated into English by the author. We are thrilled to published bilingual content because, as our project underpins, we live in a multilingual world and we want to celebrate such linguistic and cultural diversity!

En un momento de cierres indentitarios y de fronteras resucitadas, hay autores apostando por decir NO. NO es precisamente el título de la última novela de Said El Kadaoui El Moussaui, escritor de origen marroquí que escribe en catalán sobre la experiencia de quienes, como él, se entienden como “personas múltiplemente arraigadas”. Su vida, ciertamente, es una amalgama de cruces: nacido amazigh en un Marruecos del que sus padres se fueron cuando era niño, creció en España, sí, pero precisamente en un rincón que, ahora en su madurez, vive un proceso independentista. Antes de este NO (publicado en 2017, un año protagonizado por el Brexit, Le Pen o el muro de Trump), El Kadaoui ya había rondado esta aproximación en Cartas a mi hijo (2011), una obra con el elocuente subtítulo de Un catalán de los pies a la cabeza, casi; y en Límites y fronteras (2008), en la que se valía de la analogía de la enfermedad mental para situarse en un lugar capaz de vociferar un sentido común que los discursos únicos hacen parecer insensato, como aquellos “locos sabios” que cantaban verdades en la literatura tradicional.

Said El Kadaoui El Moussaui. No (2017).

The sentence in the lower part of the cover, written in Catalan, says: “Beginning to dream when you’re forty is ridiculous”.

At a moment when identities and borders are increasingly contested, there are writers who choose to say NO. NO is indeed the title of the last novel by Said El Kadaoui El Moussaui, an author of Moroccan origin writing in Catalan about the experience of those who understand themselves as “multiply rooted people”. His life is certainly a melting pot of crossings: born Amazigh in a Morocco that his parents left when he was a child, he was raised in Spain, more precisely in a spot that he now, as an adult, witnesses going through an independence process. Before this NO (published in 2017, the year of Brexit, Le Pen and Trump’s wall), El Kadaoui had already addressed this issue in Letters to my son (2011), a work with the eloquent subtitle A Catalan from head to toe, almost. He did so in Limits and borders (2008), too, where by recurring to the analogy of mental illness, he denounced the common sense that official voices make sound senseless, just like the “crazy wise men” who are the ones who speak the truth in traditional literatures.

Esta escritura centrada en las dificultades de de la vida a caballo entre culturas sitúa a El Kadaoui como parte de un pequeño fenómeno en el que, sin embargo, es al mismo tiempo una rara avis. En el panorama literario catalán han ido consolidándose en la última década voces (fundamentalmente la de Najat El Hachmi, y en algo menor medida la de Laila Karrouch) que responden a un perfil similar: son obras que reflejan, entre el testimonio y la autoficción, el recorrido paradigmático de las miles de personas cuyas familias llegaron a España como inmigrantes en la década de 1980. En su escritura, estos autores (que, a diferencia de beurs o chicanos aún no han encontrado una denominación bajo la que arroparse) recorren el laberinto de la identidad con obras que remiten una y otra vez a la misma pregunta: qué lugares de vida es posible articular entre la aculturación y la crisis identitaria permanente.

En esa búsqueda, la cuestión generacional aparece como tragedia: “yo ya no pertenezco al mundo que puebla la cabeza de mis padres”, escribe El Kadaoui. “Me miran como a un extraño, como a alguien que ha cambiado de bando. Sienten que tienen un hijo extranjero”. La hija extranjera es también el título de la última novela de El Hachmi. Pero a ese desconcierto, sus respuestas son muy diferentes. La exploración de Najat es cuánto se tarda en hacerse de un lugar, su posición es la de reivindicarse como catalana de pleno derecho. Su estrategia pasa por buscar un modo de esquivar la crisis identitarias, de cerrarlas. Escribe, en la misma línea, Leila Karrouch, la más entusiasta de los tres en lo que respecta a las posibilidades de la convivencia: “Emigrar es ganar una cultura (…) Me gusta hacer un buen cuscús para comer y una tortilla de patatas para cenar. ¿Por qué no?”

Frente a estas posturas en cierto modo benevolentes, Said El Kadaoui aborda el problema desde otro lugar: “La identidad que nos han inculcado es un embuste ideológico. Somos una mentira, una ficción o una media verdad velada con una ideología que, pobrecitos, nos empeñamos en defender”. Los frescos de personajes de sus novelas (estampas con un realismo irónico que mete el dedo en la llaga de la complejidad y la contradicción de las vidas) revelan una convicción: “O se es miembro de una tribu o se es ciudadano o se es inmigrante”. Entre esas categorías, vagando por situarse o desclasificarse, encontramos una coralidad que regresa al problema generacional: “Aquellos que soñaron alguna vez y partieron en busca de un mejor futuro, hoy someten a sus tribus a las leyes incomprensibles de las tradiciones”.

Writing about the difficulties of living in between cultures situates El Kadaoui within a relatively underexplored field in which, nevertheless, he is a rara avis. Voices such as Najat El Hachmi‘s and –to a lesser extent– that of Laila Karrouch, who have in the last decade become well-established within the Catalan literary scene, respond to similar concerns. Their works oscillate between testimony and self-fiction, and mirror the paradigmatic path undertaken by the thousands of people whose families arrived in Spain as immigrants in the 1980’s. These writers (who, unlike the beurs or the chicanos, have still not coined a name for themselves) walk through the labyrinth of identity and return, time and again, to the question: when we find ourselves between acculturation and permanent identity crises, what are the life spaces that we can embody?

In this quest, generational issues emerge as a tragedy: “I no longer belong to the world that inhabits my parents’ minds”, writes El Kadaoui. “They regard me as a stranger, as someone who has changed sides. They feel they have a foreign son”. The foreign daughter is also the title of Najat El Hachmi’s last novel. Yet they develop very different responses to the same kind of estrangement. Najat’s exploration is about how long it takes to become indigenous; her approach is to assert herself as a fully-fledged Catalan. Her strategy implies dodging identity crises, trying to foreclose them. Similarly, Leila Karrouch –the most enthusiastic of them all concerning the possibilities of coexistence– writes: “Emigrating is acquiring a culture (…) I like to cook a good couscous for lunch and a Spanish omelet for dinner. Why not?”

Unlike these somehow benevolent positions, Said El Kadaoui deals with the problem from a different angle: “The identity that has been hammered into us is an ideological hoax. We are a lie, a fiction or a half-truth veiled by an ideology that –poor us– we insist on defending”. The frescoes of the characters in his novels are depicted with an ironic realism that puts a finger on the sore spot of the complexity and contradiction of life, and they reveal a conviction: “Either you are a member of a tribe, or a citizen, or an immigrant”. Wandering for a place amongst these categories or trying to leave them behind, we note a multitude of voices that reaffirm the perennial gap between generations: “Those who once dreamed and left in search of a better future, are now submitting their children to the incomprehensible laws of traditions”.

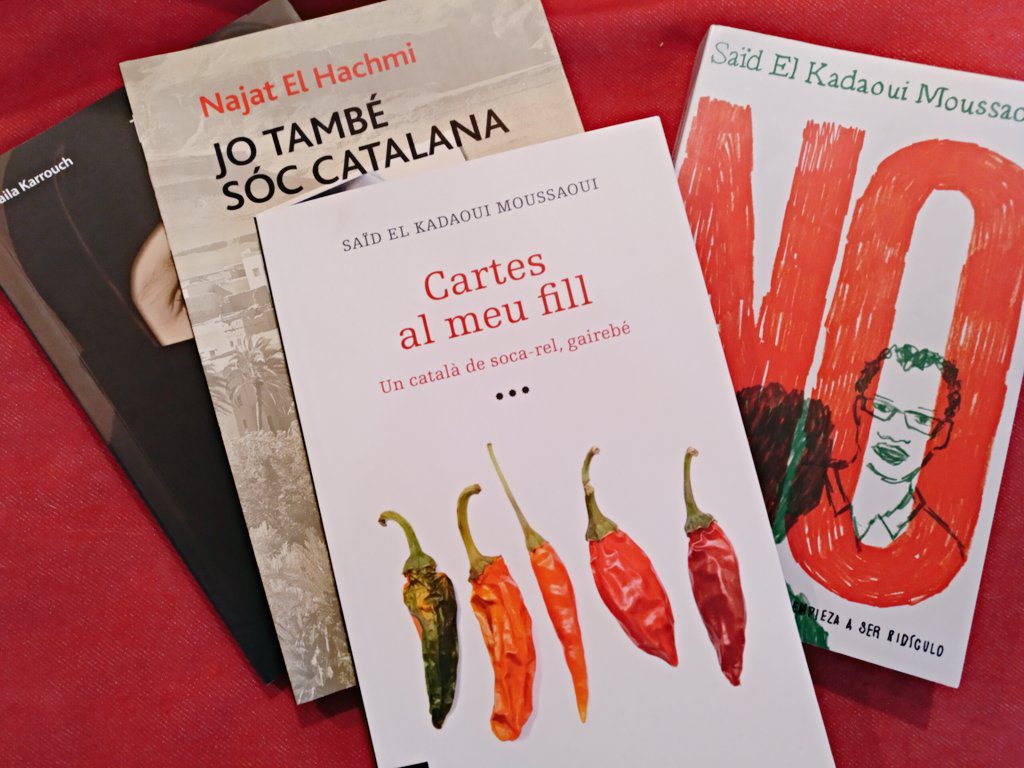

Covers of some of the books by El Kadaoui, El Hachmi, and Karrouch.

Al alter ego que El Kadaoui construye como narrador en NO, esas leyes de las tradiciones le resultan claustrofóbicas. Por eso, erige como referentes a autores como Hanif Kureishi y Mohammed Arkoun. Autores que, a su entender, “traicionan las exigencias de fidelidad enfermiza de un sector importante de sus comunidades de referencia” y se empeñan en “matar las lealtades de grupo y hacerlo mediante la escritura”. En un ejercicio metaliterario, ese narrador (un personaje obsesionado por el sexo y atormentado por sus neurosis) es un profesor universitario encargado de impartir un seminario titulado “ Narrar al otro siendo el otro”. “Me estoy convirtiendo en un especialista en esto de las identidades periféricas”, leemos, en lo que parece una reivindicación, dentro de la novela, del propio sitio que El Kadaoui considera que se le debe a una obra como la suya en un país en el que un curso de esas características ha dejado de ser ficción solo muy recientemente.

Y es que este tipo de aproximaciones, manidas ya en las literaturas anglófonas o francófonas, aparecen en el panorama literario español como una novedad casi extemporánea. Con una crítica que no se ha hecho cargo de las obras escritas en castellano en los países colonizados por España en el pasado, y un mercado editorial en el que no han proliferado tampoco las de los hijos de las diásporas, el canon literario español no se ha abierto particularmente a la world literature, ni a las teorías poscoloniales, ni mucho menos a los border studies. Es en ese vacío en el que la escritura de El Kadaoui aparece en cierto modo como inaugural, por más que en otras tradiciones se puedan encontrar muchos parentescos para su modo de indagar en la ficción como territorio en el que moldear esa identidad compleja: “Mi Marruecos es una ficción (…) Es un país que hay que descubrir, y en eso ando”.

Pero, ¿acaso andamos en otra cosa todos los demás? Mientras Said se busca, en su tierra de adopción proliferan las banderas, y, tras el triunfo de un referéndum nacionalista, se intenta decidir de qué modo construir (o no) un nuevo país. La lengua, la hegemonía cultural, la identidad, ya no son temas de minorías: España se encuentra en un momento de revisión de sus consensos, y las preguntas que no se ha hecho en términos de memoria irrumpen en términos de presente. “Lo que más miedo da de la persona diferente no es la diferencia, sino que se parezca a nosotros. Reconocer esto querría decir que hoy tú eres el forastero, pero mañana podría serlo yo”, escribe El Kadaoui. El aire que deja pasar su ventana abierta en la frontera no solo le ayuda a respirar a él.

For El Kadaoui’s alter ego narrator in NO, the laws of these traditions are claustrophobic. Hence his model writers Hanif Kureishi and Mohammed Arkoun, who “betray the sick loyalty that an important sector of their communities demands” and insist on “killing loyalties, and doing so by means of writing”. In a metaliterary exercise, this narrator (a character obsessed by sex who is tortured by his neuroses) is a professor teaching a seminar called “Narrating the Other while being the Other”. “I am becoming an expert on this issue of peripheric identities”, we read, in what might be a vindication, within the novel, of the place El Kadaoui considers that a work such as his own should have in a country where such seminars have only recently stopped being a fiction.

This kind of approach, already established in Anglophone or Francophone contexts, emerges as a belated novelty in the Spanish scene. For one thing, critics have not taken into account works written in Spanish in the former colonies, and the publishing market has also not given room to the children of the diasporas, so the Spanish canon has not particularly opened its eyes to world literature, nor to postcolonial theories, even less to border studies. In the context of this vacuum, El Kadaoui’s writing is somewhat pioneering, despite the similarities that might be found in other traditions for his way of inquiring into fiction as a territory in which that complex identity might be shaped: “My Morocco is a fiction (…) It is a country that one must discover, and that’s where I’m at”.

Still, is this any different from the concerns which the rest of us are dealing with? While Said is looking for himself, in his land of adoption flags are proliferating, and, after the triumph of a separatist referendum, people are trying to decide upon how a new country should (or should not) be built. Language, cultural hegemony, identity, are no longer minority issues: Spain is revising its consensuses, and questions linked to memory now present themselves in terms of current issues. “What is most frightening about a person who is different is not his or her difference, but the fact that he or she resembles us. Acknowledging this could mean that I am the foreigner today, but tomorrow it might be you”, writes El Kadaoui. He is not the only one who can freely breath the air that flows through his window at the border.

El Kadaoui El Moussaui, Said. Límites y Fronteras. Lleida: Editorial Milenio, 2008.

-. Cartes al meu fill. Un català de soca-rel, gairebé. Badalona: Ara Llibres, 2011.

-. NO. Barcelona: Cátedra, 2017.

El Hachmi, Najat. La filla estrangera. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 2015.

Karrouch, Leila. De Nador a Vic. Barcelona: Columnia Edicions, 2006.

Parrilla, G. & Casielles, L. “Spain”, in Hassan, W.S., The Oxford Handbook of Arab Novelistic Traditions. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 665-677.

Pomar-Amer, M. “Voices emerging from the border. A reading of the autobiographies by Najat El Hachmi and Saïd El Kadaoui as political interventions”. Planeta Literatur. Journal of Global Literary Studies. 2014, no. 1: Europe – Maghreb: exchanged glances / L’Europe et le Maghreb: les regards croisés; pp. 33-52.

Codina, N. “The Work of Najat El Hachmi in the Context of Spanish-Moroccan Literature”, in Research in African Literatures (Zeitschriftenheft), vol. 48, no. 3, Special Issue: Migratory Movements and Diasporic Positionings in Contemporary Hispano- and Catalano-African Literatures, pp. 116-130.

Ricci, C. ¡Hay moros en la costa! Literatura marroquí fronteriza en castellano y catalán. Madrid-Frankfurt am Main: Iberoamericana-Vervuert, 2014.

Leave a Reply