Amul Gyawali is originally from Kathmandu, Nepal, and recently completed an MA in South Asian Area Studies from SOAS, University of London. Amul is now applying to PhD programmes for further ecocritical study of Indian and Nepali literatures

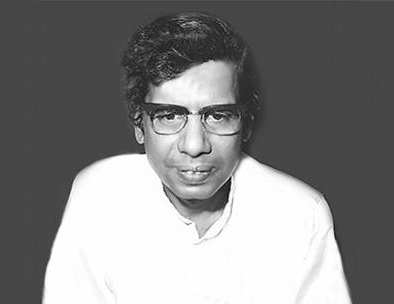

Phaniswarnath Renu (1921-1977), one of the pioneers of the ‘regional novel’ (āncalik upanyās)

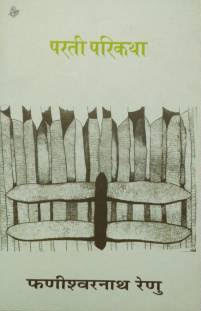

Partī parikathā (Tale of a barren land, 1957) was the second novel of Phaniswarnath Renu (1921-1977) and exemplifies his pioneering work in Hindi “Regionalist” writing, depicting life in rural Bihar with vivid clarity and through a myriad of characters and idiolects. Less famous and read than his first novel, Mailā ānchal (The Soiled Border, 1954), it was recently translated by Murari Madhusudan Thakur as Tale of a Wasteland (New Delhi: Global Vision Press, 2012, available on Amazon.in or Abe.books).

Located temporally in newly-independent India amidst Nehruvian development, and geographically by the volatile Kosi river close to the India-Nepal border, the novel tackles the entangled paradigms of post-colonial state-society and centre-periphery. Often overlooked, yet equally important, is the paradigm of man-nature, highlighting the significance of ecology alongside the social, political, and economic realities of Paranpur village.

The importance Renu placed on the natural environment is evident from the title itself. Partī parikathā—or Tale of a barren land—suggests that location functions as more than the geographic site of the novel, it is in fact a central actor. The vast tracts of barren (parti) land that surround Paranpur are the product of perennial flooding of the Kosi river every monsoon, creating a sandy, unvegetated landscape. Significantly, the barren parti is inextricably linked to the livelihoods of Paranpur’s agrarian community, as limited fertile lands in the village are distributed unevenly among wealthy landlords (zamindars) like Jittan, the novel’s protagonist.

When Jittan undertakes mysterious efforts to afforest the parti to increase agricultural land, Paranpur’s residents are suspicious and dismissive¸ having already suffered the bureaucratic state’s empty promises of land reform, through the Zamindari Abolition Act of 1950 (which plays such a major role in Vikram Seth’s novel A Suitable Boy) and a new Land Survey. It is only at the end of the novel, when Jittan engages in open dialogue with the villagers to discuss the communal and ecological benefits of his plans, that he can successfully execute his vision.

Silt deposits on the Kosi river in Bihar, similar to those described in Renu’s Partī parikathā (via Manoj Nav, Wikimedia Commons)

The novel’s non-linear narrative structure enables Renu to introduce a multitude of myths, performances, and traditions, which not only emphasize the region’s rich cultural heritage but place the events of the 1950s within the historical context of the region. Most poignant is the myth of Mother Kosi, the goddess who floods the land while escaping her evil in-laws, thereby creating the barren parti. In portraying the Kosi river in the form of a human goddess, the myth recognises nature as an active agent in shaping the history of the region.

Similarly, the myth of Sunnari Naika, a traditional ballad, presents a folk history of Paranpur’s five water pools, dug up during a famine to bring water to the village. Fittingly, these same pools are instrumental in solving the ecological issues of the 1950s, when utilized by the developmental state to provide irrigation for Jittan’s efforts to farm the parti. Renu concludes the novel by revisiting the local myths and traditions in the performance of the community theatre, which once again displays and celebrates the variegated voices and textures of the village’s cultural heritage.

Alongside local myths and cultural traditions, Paranpur’s colonial history features in the novel through the diaries of an Englishwoman, Mrs. Rosewood. Presenting this period through a colonial voice, the novel not only juxtaposes local and foreign perspectives of Paranpur, but also provides a first-hand account of the colonial encounter in Bihar. Beyond Mrs. Rosewood’s bizarre ambition to become a gopi and satiate her infatuation with Lord Krishna (Jittan’s father), the diaries bring to light the colonial practices of inclusion and exclusion, resulting in uneven land distribution and social disunity amongst the villagers. The village finally confronts this colonial legacy through a community theatre, which reintroduces a cultural space for community cohesion.

Parti parikatha (1957) by Panishwarnath Renu

In Partī parikathā, environmentalism and developmentalism are not antithetical; rather, Renu’s concerns lie in the ways in which both are carried out. In fact, it is an amalgamation of the two that is proposed as an alternative to the inadequacies of the postcolonial bureaucratic state at the end of the novel, whereby the developmental state aids Jittan’s efforts to farm the parti, and in doing so, increase fertile land for agriculture. Having established the inseparable links between the local community and ecology throughout the novel, Renu demonstrates that any eco-developmental project is only feasible when it actively involves and benefits the local villagers.

Kathryn Hansen writes that Renu’s regional writing challenged an urban, cosmopolitan trend in Hindi literature, drawing “the reader into the village, into awareness of its customs and traditions, its patterns of thoughts” (Hansen 1982: 1). It is here that we can identify the value of reading Partī parikathā, as Renu showcases a vibrant cultural tradition away from the cosmopolitan sphere, aided by the multiple voices, traditions, and histories that shape the region. At the same time, these voices provide any reader of Partī parikathā a glimpse into the different patterns of thought even within the village, challenging any perception of the village as a homogenous entity. Further, an ecocritical reading of Partī parikathā introduces yet another voice and layer of nuance to Renu’s wonderfully balanced regional writing.

Hansen, K., 1982. ‘Introduction: The Writings of Phanishwarnath Renu.’ Journal of South Asian Literature, 17(2), pp.1-4.

Renu, Phanishwar Nath. 2017 [1957]. Partī parikathā. New Delhi: Rajkamal Paperbacks.

—, 2012. Tales of a Wasteland, tr. Murari Madhusudan Thakur. New Delhi: Global Vision Press.

Leave A Comment