Alireza Abiz is an Iranian poet, literary critic and translator who has written extensively on contemporary Persian literature and culture. He studied English Literature at Mashhad and Tehran universities and received his PhD in Creative Writing from Newcastle University. Abiz has rendered leading English-language poets such as Basil Bunting, Derek Walcott, Allen Ginsberg, and C.K. Williams into Persian, and has won awards for his translations. He is also the author of six collections of poetry in Persian. Abiz is currently an independent researcher based in London, and his book ‘Censorship of Literature in Post-Revolutionary Iran: Politics and Culture since 1979′ is forthcoming from I. B. Tauris.

While Iran is usually portrayed as a hostile, self-isolating country refusing to accept the need for international cooperation, ironically the state-sponsored ‘World Award’ category for the ‘Book of the Year’ prize actually reflects a more multilingual vision than many major Western prizes such as the Nobel Prize or the Man Booker. Additionally, this award has been presented to scholars from countries with which Iran has strained diplomatic relations, including the United States. As The Book of the Year just posted its call for entries for the 2018 awards, it is worth examining what this prizes considers ‘the world’.

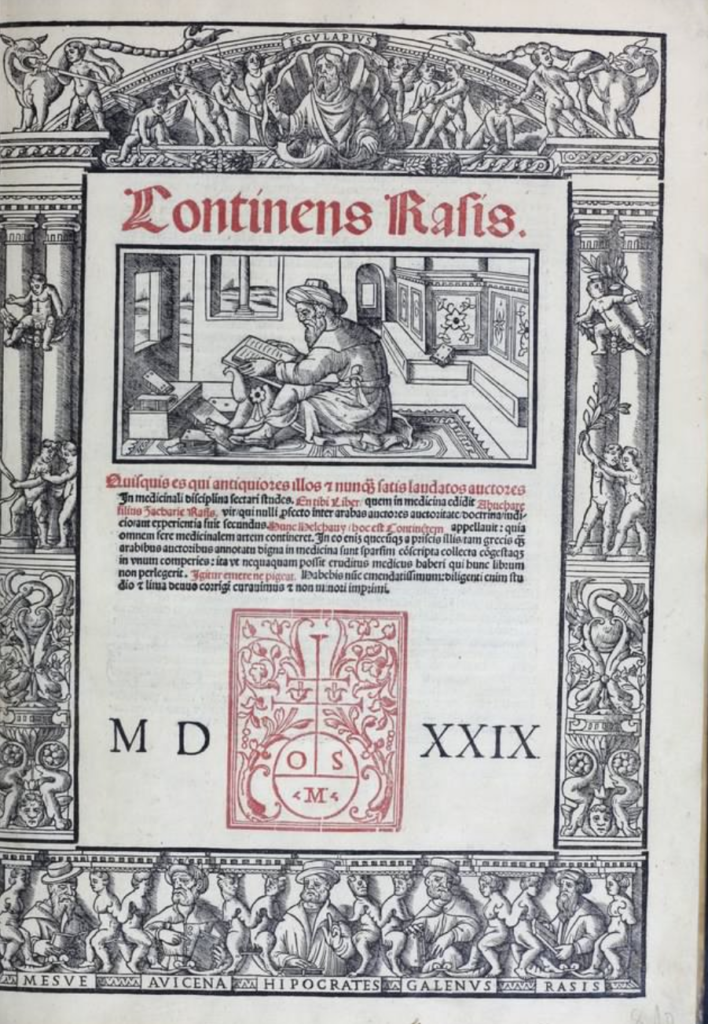

In its last round, the World Award considered more than 2,500 books authored from languages as diverse as English, French, German, Chinese, Arabic, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Georgian, Armenian, Turkish, Azeri, Bengali, Finnish and Serbian. Awards were then granted to scholars from Turkey, Romania, Finland, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, Spain, France, The United States, and Germany. Books for the two prize categories, Islamic Studies and Iranian Studies, were judged by a panel of more than 70 international experts who evaluated a longlist of 179 titles and chose a shortlist of 24 books. Compare this to the six judges of the Nobel Prize Committee, who apparently speak a total of 11 languages. In the final stage, 10 awardees were chosen and the award also recognized Timothy Wright and Mohammad Ali Shomali for their work on interfaith dialogue. Winning titles which spoke to the centuries-long legacy of Persian literary exchange with other cultures and languages include The Sanskrit, Syriac and Persian Sources in the Comprehensive Book of Rhazes by Oliver Kahl and The Love of Strangers: What Six Muslim Students Learned in Jane Austen’s London by Nile Green. There is also another prize category called the ‘Regional Book Award,’ which considers books on Iranian Studies from the Indian subcontinent, where Persian has long been a language of high literature.

Acknowledging this fairly expansive list is not to say, by any means, that the award reflects an unproblematic construction of the world, or of an ‘Islamic World’. A look at the winning titles indicates a strong tendency to award books which conform to the cultural policies of the government. In regards to Islamic Studies, the award is fairly inclusive of different sects, but has started shifting toward Shiite studies in recent years. However, controversial ideas on Islam, e.g. works by Islamic reformist thinkers, have no place in this award. Books which challenge the official state discourse on Islam are usually ignored, and the works of classic philosophers seem to be a safer bet.

In the case of Iranian Studies, the committee’s standards make it difficult to present an expansive version of the field. For example, no work of contemporary literature has ever been nominated for a prize, and only translations of Persian classical texts can be found among the winning titles. However, despite the state’s heavy promotion of Shiite Islam as the main feature of Iranian identity, a book on Zoroastrian studies won this prize last year (Zoroastrianism was the primary religion of Iran prior to the Islamic conquest in the 7th century). For the national ‘Book of the Year’ award, which considers Iranian authors, the committee often has difficulty making nominations as the majority of fiction and poetry of high literary value do not conform to the authorities’ strict cultural standards. In the World Award, a similar problem can be observed. Many of the books written by scholars on contemporary Iran do not conform to the cultural principles set by the system. Some Iranian scholars in overseas academic centers are outright boycotted by the Iranian cultural authorities, and thus their writing has no chance of being nominated.

Another gap in the award is made by the fact that not everyone is willing to submit their books for consideration due to the highly-politicised domain of Iranian Studies and even Islamic Studies. A considerable number of Iranian scholars and authors who write in non-Persian languages do not look favourably at the cultural policies of Iran, or at its Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Among some circles, even sending a book for consideration might bring disrepute. Every year, tens of important books on contemporary history, sociology and politics of Iran are published in different languages, but they don’t find their way into this award because of their critical stance. This is unfortunate, as the award could be a chance for readers and scholars who care about Iranian Studies to discover the most important new books in the field- regardless of their stance towards Iran’s government.

Despite its limitations and biases, The World Book Award deserves further examination and acknowledgement outside of Iran. At the very least, shouldn’t the Book of the Year’s construction of a ‘world’ be an interesting point of comparison to that of other awards, one that could help Westerners see the limitations and biases in their construction of a ‘world’ as well? Doesn’t seeing the limitations of this prize also make one wonder what is left out of other, more internationally-known prizes?

Leave A Comment