Overcoming the limitation of an approach that is confined to strict national boundaries and open our horizons to the multifacetedness and complexity of cultural production, exchange and reception on the Asian continent in case studies from Japan and South Korea, China and India.

In recent years, a growing number of scholars in the field of literary studies and beyond have emphasised the need to regard Asia as a historically grown cultural sphere with overlaps and commonalities. The two presentations of this event stood in line with Karen Laura Thornber’s studies on the literary contact nebulae (in Empire of Text in Motion, 2009), Chen Kuan-Hsing’s Asia as Method (2010) or Margaret Hillenbrand’s East Asian Comparative Literature (2007), to name but a few, in that they outline literary flows within Asia beyond the “East-West paradigm” in which “the West” often becomes the ultimate tertium comparationis. Focusing on Asia as a dynamic site of cultural exchange, Nadeschda Bachem (SOAS) and Yan Jia (SOAS) presented case studies from Japan and South Korea, China and India, respectively, to overcome the limitation of an approach that is confined to strict national boundaries and open our horizons to the multifacetedness and complexity of cultural production, exchange and reception on the Asian continent.

Nadeschda Bachem’s paper, Re-articulating the Colonial Experience: Language and Power in Postcolonial Japanese and South Korean Short Fiction, compared two pieces of short fiction that deal with the history and effects of Japanese imperialism on the Korean peninsula (1910-1945): the South Korean writer Son Ch’angsŏp’s To Live (Saenghwalchŏk, 1954) and Japanese author Kobayashi Masaru’s Ford 1927 (Fōdo 1927-nen, 1956). In detail, she traced how the writers use issues surrounding language to reveal the contradictions and frictions within the colonial and postcolonial power relation between former metropole and colony.

In her discussion of To Live, she dwelled on the ideology of Korean monolingualism that became fundamental to the South Korean state after the liberation and the Korean War (1950-1953). The pressure to write in Korean impacted on authors who had been educated in Japanese during the colonial period and only learned to express themselves literarily in Korean after 1945. To Live challenges the doctrine of monolingualism in an ironic way and mocks its internal contradictions.

Ford 1927, meanwhile, points to the profound trauma the colonial period left on the Japanese side as well and highlights Japan’s ambivalent position within the newly-forming Cold War world order under American hegemony. The text takes on dichotomising discourses on the colonial period.

In her conclusion Nadeschda emphasised that the deep-seated impotence left on both sides of the national divide by imperialism, war and defeat is often expressed as linguistic impotence or the need to adapt to the respective hegemonic language. Furthermore, she pointed out that literature often challenges the simplistic coloniser-colonised or perpetrator-victim binary that is frequently found in political discourse and thus helps us to a more nuanced understanding of the memory of the imperial experience in East Asia.

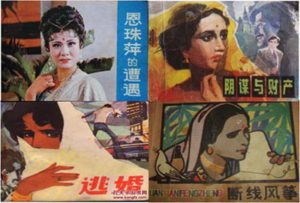

Chinese lianhuanhua (illustrated storybook) adaptations of Kati Patang

Shifting the geographical focus westwards, Yan Jia’s paper examines the phenomenal reception of Gulshan Nanda’s (1929-1985) romance novels in China. From 1978 onward, seven titles by Gulshan Nanda were translated into Chinese, amongst which Duanxian fengzheng (“Kati Patang”) was adapted into various kinds of regional theatrical forms and illustrated storybooks. While Gulshan Nanda was largely regarded as a “pulp fiction writer” and had no place in the mainstream literary circles in India, his works have always been included in China’s academic discourse about Indian literature and occasionally enjoyed the status of “canon”. This stark contrast propels us to ask: how did the processes of decoding and recoding play out through the transfers of Gulshan Nanda’s texts from India to China?

Yan started his analysis at the level of general readers. In the post-Cultural Revolution China whose readers craved for transgressing conventional ways and subject matters of reading, Gulshan Nanda’s romances stood out not only for their “exotic” Indian setting, but also for the author’s skilful deployment of melodramatic narrative devices to elicit the readers’ emotional responses. He then moved on to look at the level of agents, especially translators and critics. He argued that Gulshan Nanda’s romance fiction was chosen by the emergent Chinese translators of Hindi literature, mainly because its blending of the “romantic” and the “social” fit squarely into the translators’ expectation to introduce a “modern” India characterised with its budding middle-class’s sensibility and sociability while not breaking away from the conventional norms of China’s literary criticism which tended to foreground the social-critical functions of literary works.

Lastly, Yan laid out the three ways in which Chinese translators and critics used Gulshan Nanda’s romance novels to address their own concerns: (a) to elevate public morality; (b) to evoke an awareness of social problems by linking the Indian text to the Chinese context; and, (c) to combat the bigotry about popular literature that prevailed in China’s literary field by highlighting the refined elements in Gulshan Nanda’s works. In these ways, Yan concluded, Gulshan Nanda was attached with a lot new significance, both social and literary, which helped elevate his status in China’s perception of Indian literature.

The SOAS Centre for Cultural, Literary and Postcolonial Studies (CCLPS) runs a regular Critical Forum in which PhD students are invited to present their research in conversation with one another. Sign up to the MULOSIGE newsletter to receive more information about future meetings of the Critical Forum.

Leave A Comment