Ghazala Raees is a visual communication designer, currently pursuing her MA in Critical Media and Culture Studies at SOAS University of London. Her current research revolves around the dynamics of class hierarchies and the conflict between traditions and modernity as portrayed in Pakistani Media. Her other interests include anything related to food and an involuntary Bollywood addiction.

With the rise of the information society in the recent years, the impact on cultural production has been prominent and drastic (Frank Webster 2006). A move towards participatory media platforms and the introduction of mediums such as ‘memes’ and ‘vines’ have evolved the practices of visual culture by bringing a level of freedom of expression that was otherwise unknown. Such freedom which, in one way allows for the producer of content to reach the maximum number of audience with minimum censorship, also results in the explicit usage of multicultural tropes, which may or may not be interpreted in the intended way by the audience. Webster (2006:20) explains the appropriation of such tropes by saying, “…in the postmodern era we are enmeshed in such a bewildering web of signs that they lose their salience. Signs come from so many directions and are so diverse, fast-changing and contradictory, that their power to signify is dimmed. Instead, they are chaotic and confusing.”

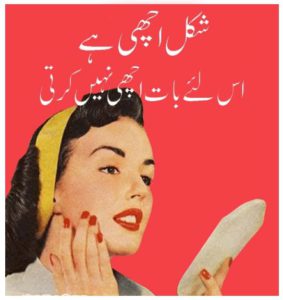

Fig: 1 – Translation: I look good that is why talk good. A comment on the popular saying, if you don’t look good at least say something that’s good

Taking advantage of these liberties and opportunities provided by modern day media, amidst this “chaos and confusion”, a fictional character is born in Pakistan who takes social media by storm. She portrays the opposite of what an average Pakistani woman is expected to be, in return becoming the representation of the inner voice of a large majority of local women. The character refers to herself as “Khabees Orat.” Where “orat” can literally be translated into “woman”, “Khabees” is a combination of “notorious,” “wicked, “dishonorable,” “devilish” and “corrupt” qualities.

She is blunt and offensive. She does not care for the ways of the society. She is independent, bold and unapologetic. The character, through social media posts, places herself in everyday situations and shapeshifts into various roles a woman is supposed to undertake such as a wife, or a mother. By using humor and sarcasm as her weapons, she challenges the unquestioned norms, the suppression and exploitation of women in the Pakistani society. She fills the role of a superhero for the average middle-class women in Pakistan. As she herself comments in an interview “I get hundreds of messages…most of them are by girls with one thing in common that they love me because I say what they want to say but they can’t”

Her posts are catchy, colorful and easy on the eyes, along with her quotes which seem so fun and harmless that it’s rare that one notices a detail so obvious; despite having the most in-depth understanding of a Pakistani woman, how she thinks and what she wants, ‘khabees orat’ herself is not a traditional, local woman. She does not look Pakistani or South Asian. She is white! White in the color of her skin. White in the way she dresses up. White in the way she carries herself. The absurdity of the juxtaposition of a white woman’s vintage illustration with Urdu text becomes visible once you see it that way. However if one puts in the effort to analyze it further, they can see how a comparison so vast, refers to so many different layers of interpretations, each completely sensible and plausible.

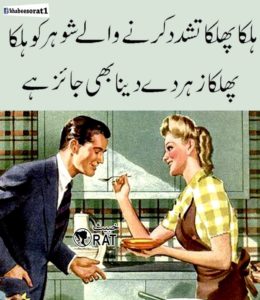

Fig: 2 – Translation: To the husband who believes lightly beating his wife is acceptable, giving him some poison is also acceptable. Retaliation toward a ruling passed by religious clerics, claiming that ‘lite beating’ of disobedient wife is acceptable.

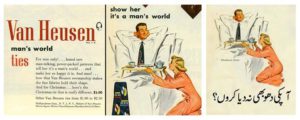

The character in these posts, is also not any white woman, she is the symbol of the ‘perfect, obedient, housewife’ used in the awfully sexist American advertisements of 1950’s and 1960’s. The imagery being used in the adverts and this blog, however refers to a stereotypical understanding of a woman and her role in the society, their context and meanings in both cases are completely opposite. Where one artwork (Fig 3) celebrates the ideas of patriarchy and misogyny, with captions like “It’s a man’s world,” on the other hand, the same artwork challenges its claim with a caption (rough translation) “Do I also need to go to the bathroom with you too?” Calling out on the incompetent and dependent nature of the male species so proudly highlighted in the original poster. Nicholas Mirzoeff (1999) explains such inconsistency in the meaning of an image by pointing out that, “…visual image is not stable but changes its relationship to exterior reality at particular moments of modernity.” Hence through the use of very specific visual elements, including the choice of font for the Urdu text and its composition, that can directly be compared to locally produced Urdu magazines also known as ‘Urdu Risalay’ or ‘Urdu Digest’ whose primary audience is the average Pakistani woman Khabees Orat portrays, in today’s day, she questions the ideas of modernity in relation to the contemporary life of Pakistani Women. Through this ‘in your face’ approach and the belatedness of these illustrations Khabees Orat makes an effort to point out how times have changed and that her depiction in a 50’s poster is not what her kind can be reduced to anymore. It’s this odd combination of a clash and synergy between the two cultures that make these posts so successful.

Fig: 3 – Translation/context: (Roughly) since I’m doing everything for you, shouldn’t I accompany you in the bathroom too?

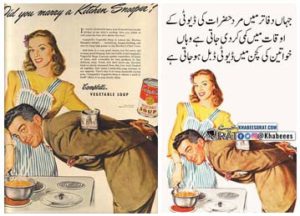

The white woman in some cases acts as a role model for the Pakistani women, someone who knows how to stand up for herself, someone they can look up to. Other times she may become someone who the Pakistani women can point fingers at. Either way, beneath the humorous, sarcastic comments, khabees orat, through this bi-cultural attack, sheds light on some very deep realities surrounding the life of Pakistani women. The designer’s one minor choice, whether deliberate or accidental, has taken the image from being an ‘innocent meme’ to the debates of; a) modernity and the role of women in the society and b) two conflicting identities – the white woman and the brown.

Fig: 4 – Translation: As soon as office hours for men are reduced, kitchen hours for women are doubled.

Khabees Orat is one example, every day we are exposed to such information, where symbols, icons, and attributes are borrowed in the name of popular culture and humor. We derive pleasure from them without realizing what they portray on subliminal levels. Webster quotes Jean Baudrillard to have said, “there is more and more information, and less and less meaning” (1983a, p. 95). There is more and complex information all around. However, there is less meaning because, in this rapidly changing environment of today, there is no time or liberty to realize deeper meanings. We have lost the patience to truly ‘see’ and understand something.

References:

- Frank Webster. 2006. “What is an information society,” in Theories of the Information Society

- Nicholas Mirzoeff. 1999. “What is Visual Culture?”

- An Interview with Khabees Orat Fictional Character by Creative Khadija. 2016 –

Leave A Comment