Akeder Ahmedin Issa is an Eritrean writer, critic and journalist. He graduated from the University of Asmara in 2002 with a BSc degree in Electrical Engineering . In 2012-2013 he attended an advanced course on “creative-cum-critical response to literature” in the College of Arts and Social Sciences in Adi Keih. He is currently the chairperson of the Eritrean Film Rating Committee (EFRC) and senior editor at Hdri Media, where he edited and published more than 20 books of different genres. His literary works include short stories, poems, plays, film scripts, magazine and newspaper columns, and research articles on Tigrinya literature. He has published two books in Tigrinya and produced an award winning feature film in 2014. Ten of his plays have been performed over the years at renowned theatres across Eritrea.

The Tigrinya Short story in Eritrea emerged in the 1980s as a result of different socio-political developments in two locations: in Sahl – the center of the armed struggle for the independence of Eritrea – and in the capital Asmara. In both places, translations, training workshops, and literary competitionsplayed a significant role in developing the Tigrinya short story.

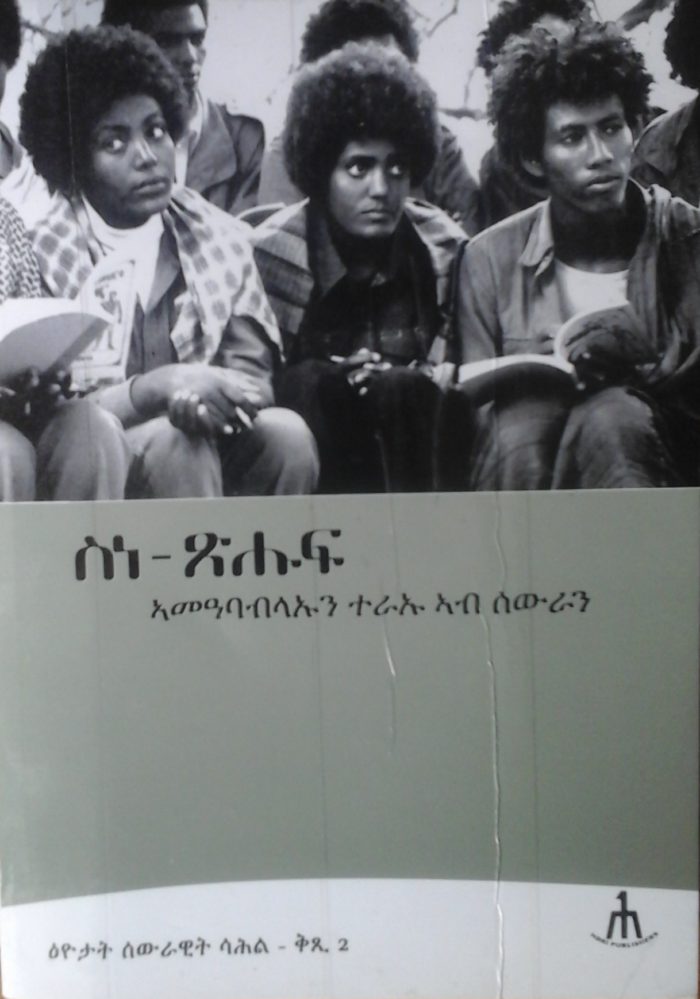

In Sahl, from 1981 to 1984, short stories from Russia, China, Vietnam, and other states of the socialist bloc were translated into Tigrinya by the Department of Political Agitation of the Eritrean Peoples’ Liberation Front, the leading national liberation movement. Fighters read them at the front and were inspired by them to create stories of their own, using characters and plot arrangements related to the Eritrean situation. Such translated literary works stimulated the fighters to think consciously about the role of literature in society, which resulted in the publication, on the part of the Department of Political Agitation, of a critical work of seminal importance: “Literature: Its Development and (its) Role in Revolution” (“ስነ–ጽሑፍ፡ ኣመዓባብላኡን ተራኡን ኣብ ሰውራ”, 1982). Its preface decries that though the need for producing quality revolutionary literature had been felt for many years, not much had actually been written. The document’s primary objective was, therefore, to encourage writers to produce literature of their own. In addition, the document was aimed at fostering discussion on the kind of literature that would suit the nature of the liberation struggle. Thus, the text was pivotal in promoting the growth of literature and shaping the attitude of the fighter-writers towards it.

Short story competitions produced significant results during the armed struggle for independence. As discussed below, even after Eritrea’s Independence literary competitions continued to play a key role in promoting short story writing. The three competitions held in Sahl between 1985 and 1987 led to the emergence of many new writers. The last of these, held during the cultural week in September 1987, proved the richest and most successful. A total of 194 participants took part in the competition, which also included Eritrean writers in exile. While most of the short stories were in Tigrinya, stories were also submitted in other Eritrean languages: Arabic, Tigre, Bilen, and Saho. In addition, an extensive critique of the stories was published in 1988. Titled “Critical review of the third literary competition” (“ነቐፌታዊ ገምጋም 3ይ ውድድር ስነ- ጽሑፍ”), the document was the result of in-depth discussions among members of the jury, and was edited by Solomon

Tsehaye and Issayas Tsegai, two prominent Sahl writers and members of the judging committee. In the following years, the document served as a critical blueprint for other writers, as they entered the literary scene.

Parallel to developments in Sahl, literary activities flourished in Asmara as well. During the Ethiopian rule, writers were heavily influenced by Amharic literature, mainly because Amharic was the language used in Eritrean institutions of learning. Several short stories, like O Henry’s “The Last Leaf” were translated into Amharic. Kuraz Publishers, one of Ethiopia’s leading publishing houses, motivated writers to publish their work in Amharic by subsidizing the publication of their translated works. Kuraz had bookshops in many cities of Ethiopia, including Asmara. The Asmara bookshop sold books at cheap prices, making available to Eritrean readers and aspiring writers novels and other literary texts from which they could learn new literary techniques.

Another aspect of literary activity in Asmara was the training sessions organised from time to time for aspiring writers. In 1988, the Ministry of Youth and Culture of Ethiopia organised an eight-month literature training programme. Though the medium of instruction was Amharic and the examples used for the course were from Amharic literature, the programme’s literary outputs were in Tigrinya. The training gave Eritrean Writers a basic understanding of the short story genre and its techniques. This inspired the production of a large number of Tigrinya short stories, which remain for the most part unpublished. The writers read them aloud at various social and community gatherings. The implicit aim of the course was actually to create pro-Ethiopia Tigrinya writers and to use their writings as a propaganda weapon against the struggle for independence waged by Eritreans. Pro-Ethiopian literary works were strongly promoted and writers were encouraged to read them aloud on different public occasions.

In the summer of 1994, one year after Eritrea’s independence, the National Union of Youth and Students of Eritrea started a three-month literature course. The course proved to be a turning point in the history of Tigrinya literature. Almost all the prominent Tigrinya short story writers are graduated from that course. Literary competitions were organised in all the annual Eritrean national festivals after independence. The competitions held between 2005 and 2008 deserve special mention. The 2005 competition was organised by the Department of Culture. Apart from offering prize money, it announced the publication of the highest-scoring short stories in the form of an anthology. The resulting anthology, titled “12 stories” (“12 ዛንታታት”), was duly published in 2006. The state-sponsored publication of the best short stories was a significant development, as it offered to hitherto unpublished writers an institutional avenue to publish their short stories – a much needed motivation to young writers. Similar short story competitions and publications continued in 2006, 2007, and 2008.

There is certainly the potential for further in-depth studies of the formal and technical aspects of Tigrinya short stories, as well as further comparative analysis with short stories in other regional languages, especially Amharic and Arabic.

Thank you Akeder, very informative and suggestive. I wonder whether any of these stories have been translated (into English? French? Italian? Amharic?) and what you would recommend for translation. Also, do you know which Russian, Chinese, and Vietnamese pieces were translated? Anyone that became particularly a favourite? Best, Francesca