Edna Mohamed is an MA Postcolonial Studies student at SOAS, University of London. Her current research examines de-linking practises and liberation movements within the cultural form from a Black feminist lens. Her other interests are in race studies, the Muslim diaspora, postcolonial environmentalism and gender studies.

Contextualising the politics of the South African Land Fear through the Plaasroman genre and J. M. Coetzee’s ‘Disgrace’

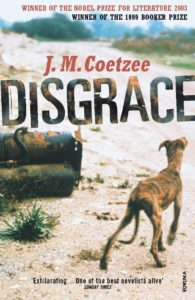

J.M.Coetzee Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2003

Under European colonialism, South Africa’s native land act of 1913 saw Black individuals stripped of their right to own land. The land act, further reinforced through apartheid, was a means of restricting the amount of power Black South Africans had over their country. Through controlling access to the formerly owned property, the system placed Black South Africans into a state of subjugation and inferiority by isolating the link between the individual and the land.

As it currently stands, white people in South Africa occupy 23.6 percent of farmland, which increases to 73 percent once accounting for land that was privately acquired, compared to the 1.2 percent owned by Black South Africans. But, even in the South African post-apartheid environment, land politics are still at the heart of South African society. However, with the development of land reforms in South Africa, the re-appropriation of land to Black South Africans is seen as an attempt to reverse the effects of the colonial land ruling and return what had once been violently stripped away.

But, the importance of land and its relation to the people who live in that space has created its own genre within the South African literary canon. The plaasroman genre, as its called and coined by the writer J. M. Coetzee, or the farm novel, sets out to respond to the developing culture of urbanisation and its relation to the rural setting. With, Coetzee referring to the genre and the farmer as being “the manifestation of the lineage in historical time is the farm, an area of nature inscribed with signs of the lineage: with evidences of labor and with bones in the earth” For Coetzee, the farmland is crucial in constructing a genealogy of South African existence. Through emphasising this notion of ‘historical time’ the farmland exists in a space that is constantly questioning the changing power dynamics of land and ownership. Theorist Harry Harootunian also refers to this temporal difference through noting the difference between ‘historical time’ and ‘everyday time’, in which one version is dependent on national histories that reflect global systems, and the other is focused on a difference.

Yet, the plaasroman, as Jennifer Wenzel notes, “establishes very specific criteria for land ownership, however. At a time when many farmers were being forced to sell their farms, the plaasroman characterized the land market as an illegitimate means of negotiating land ownership, for it dismissed the rights established by generations of family labor” By characterising the genre as focusing on the illegitimacy of the land market, the farmland becomes a space that alienates white farm owners and instead emphasises the disregard for the history of the land, itself. Thereby platforming generational land ownership over colonial theft.

Cover image of Disgrace, by J.M.Coetzee

In Coetzee’s seminal novel, ‘Disgrace’, the plaasroman device is utilised as an alienating and transitory force that explores the ways the characters in the novel navigate a post-apartheid environment. The novel follows the protagonist, David Lurie, a white South African professor that has left Cape Town in lieu of rape charges, and moves to his daughter’s farm in East Cape. Within the novel and alongside the plaasroman device, the theme of white male privilege runs concurrently with the politics of the farmland. Not only is Lurie able to move into both spheres, the Metropole and the pastoral, but, it is the assumption that he would be able to maintain the status he had in both spaces, that is indicative of Lurie’s own sense of entitlement. However, when arriving in East Cape Lurie realises that it’s unrealistic to assume that both settings reflect the same perception to his being; exposing his own naivety that the farm, or the pastoral setting, is outside of the politics of the metropolis. That in attempting to belong to the wider South African environment, David Lurie instead displaces those native to the land.

Lurie encompasses this tension between the conceptions of old and new South Africa and navigating a space of where white and Black South African power dynamics are constantly changing. Depicted most explicitly through Lurie’s relationship with Petrus, a Black South African working on the farm, Lurie is only able to understand Petrus by reducing his needs to only accounting towards the acquisition of land. Lurie states, ‘Petrus will not be content to plough forever his hectare and a half […] to Petrus lucy is still chickenfeed: an amateur, an enthusiast of the farming life rather than a farmer. Petrus would like to take over Lucy’s land.” Lurie utilises land fear and the racialised notion of the ‘scary’ black man against the ‘innocent’ white women to make this distinction that one is more humane than the other; constructing a binary that forces the non-human other in this relationship to only think and speak on a superficial level. Moreover, Lurie leaves out the ways the land he is so afraid of losing was originally stolen through, sustained, colonial politics of oppression and the subjugation of Black people. Ultimately, the narratives surrounding Black South Africans and their connection to the pastoral setting are, primarily, reduced into one-dimensional figures that maintain different modalities of control across spheres.

By contextualising the politics of South African land ownership through the literary plaasroman genre, the importance of the land and the individual is, crucially, constructed. The connection between fiction and colonial politics, albeit a common relation, allows us to understand how specific colonial politics are sustained in an imagined environment. To, as a result, step out of our own direct realities to perceive the importance of South African land ownership and the revolutionary potential of re-appropriation.

J.M.Coetzee., White Writing: On the Culture of Letters in South Africa. (New Haven: Yale UP, 1988)

Coetzee, J. M. “Farm Novel and ‘Plaasroman’ in South Africa.” English in Africa, vol. 13, no. 2, 1986, pp. 1–19. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40238587.

Nicole Devarenne (2009) Nationalism and the Farm Novel in South Africa, 1883–2004, Journal of Southern African Studies, 35:3, 627 642, DOI: 10.1080/03057070903101854

Bibliography

Coetzee, J.M.. Disgrace. [London: Vintage 2000, 1999]

Coetzee, J. M., White Writing: On the Culture of Letters in South Africa. (New Haven: Yale UP, 1988)

Harootunian, H. “Remembering the Historical Present.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 33, no. 3, 2007, pp. 471–494. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/513523.

Wenzel, J. “The Pastoral Promise and the Political Imperative: The Plaasroman Tradition in an Era of Land Reform.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 46 no. 1, 2000, pp. 90-113. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/mfs.2000.0014

Leave A Comment