Wanga Gambushe is a Doctoral Candidate in the African Languages Department at SOAS, University of London. The focus of his PhD study is the development and use of African languages in higher education in South Africa. His research interests include language policy and planning, lexicography and translation studies

This post is part of a MULOSIGE series in response to the recent publication of a special issue of the Journal of African Cultural Studies entitled ‘Contemporary Conversations: Is English an African Language?’ In particular, this series responds to a pair of articles – one by the Kenyan scholar and author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the other by the Nigerian academic Biodun Jeyifo – that take opposing stances on the position of English in African literatures, reigniting the debates between Ngũgĩ and authors such as Chinua Achebe in the 1970s and 1980s. This series is timed to reflect on the SOAS African Literature Conference, which takes place on 28 October 2017. Check out Mohamed Bouya Bamba’s post that also responds to the articles by Ngũgĩ and Jeyifo.

Decolonization and transformation

On 9 March 2015, a bucket of faeces was emptied on the statue of Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town. With this began the #RhodesMustFall (RMF) movement. RMF gained headlines across South Africa and abroad for months as UCT students protested that the statue of Rhodes must be taken down. Rhodes was one of the white men who came, conquered and lived like kings, just like the “friends” that Donald Trump recently declared had come to Africa to get rich; the same day, he created the country “Nambia,” that exports covfefe. During and after the fall of Rhodes, students spoke loudly about the need to decolonize the curriculum and transform higher education. Interestingly, in the process of talking about the need for decolonization and transformation, very little was said about language, about the question of the hegemony of the English and the role of African languages in decolonization.

The removal of the statue of Cecil Rhodes from the University of Cape Town, 9 April 2015 (photo by Desmond Bowles, via Wikimedia Commons)

The only language reference in RMF was the anger directed at Afrikaans as the language has been used as a means to exclude black students at the former Afrikaans universities. It was easy to target Afrikaans, because after all it “is/was the language of the oppressor.” The reason why little was said is a simple case of English hegemony in the intellectual space, that it is absorbed and reproduced as something only natural; how else does one show their intellectual dexterity, if not through English? There is an acceptance and internalization of the highly problematic idea of English competence – with the “correct” accent – and intelligence. Speaking to my brother a few weeks ago, I asked if he had read an isiXhosa novel that was one of the books he took from my collection. His answer was, no, he had not read it an isiXhosa book would make him “dom” (“stupid” in Afrikaans). Even though I know this was a joke (because he is the one who sent me into this African languages scholarship path), such talk is believed by many, that African languages are not worth anything, that they are “dom,” that they will make you “dom.” Giving the keynote address at the SOAS Africa Conference 2017, the Emir of Kano, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, asked why it is that the less Nigerian he sounds, that somehow makes him seem more accepted as being intelligent, more than would have been the case if he sounded “more” Nigerian.

Portrait of Credo Mutwa (1921-) by Phabellis (via Deviant Art)

The historical privileged status that the English language continues to enjoy in the continent was achieved through the suppression of African people, their languages and cultures. It is no secret that many of the freedom fighters and liberation activist that later become the leadership of post-independence African states were products of missionary education, and it is no secret that missionary schools had a clear agenda of spreading Christianity and British culture. For the missionaries, to be Christian meant to be British, even though Christianity as a religion emerged out of Middle East cultures. By the time Christianity was brought to Africa, it was loaded with British cultural supremacy over Africans. In the critically acclaimed book, Indaba My Children (1964), Credo Mutwa bemoans the imposition of white culture and religion upon the peoples of Africa. Mutwa argues that through Western education and religion, Africans were bent to the will of the colonizers – but today the very same Westerners are inclined to doubting the very same religion and are turning around and calling those “who cling to the teachings detribalised fools.” During the time I have spent in the UK it has been interesting how so many people define themselves as agnostic, not religious or atheist, when in Africa a lot of people still do cling to Christianity. With all this, what I am saying is that colonialism shaped a lot of the ways we view the world, therefore we must never lose sight of how English and Christianity came to be part of our African experience.

Theorizing our Experiences

The power of language, and the power of theorizing and defining your experience has been demonstrated clearly by the Afrikaner in South Africa, who developed their language aggressively as a way to elucidate their own existence and counter British dominance over them. Afrikaans as a language was standardized only in the early 1920s, over a century after isiXhosa (the first South African language to be written down) was standardized. Within 30 years of its standardization, it was used across the curriculum, from the 1st Grade to PhD level, with universities like Stellenbosch University designated as Afrikaans universities. The introduction of apartheid came with an aggressive English/Afrikaans bilingualism policy. This policy is still alive and well at a structural level within the public sector as some documents still are still written in both languages.

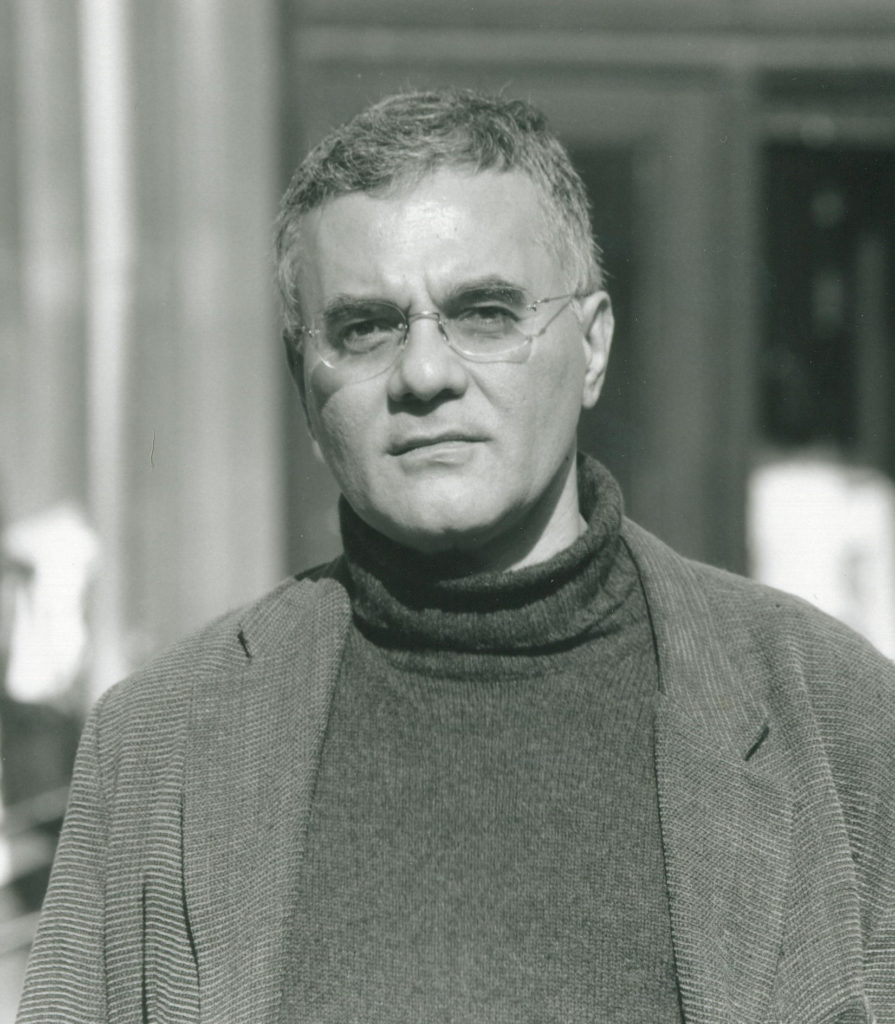

Mahmood Mamdani (1946-) (via Wikimedia Commons)

Mahmood Mamdani, speaking at the Annual Thabo Mbeki Lecture 2017, argued that the RMF and #FeesMustFall (FMF) students must widen the scope of their demands. They must agitate for the creation of institutional structures/spaces where the experiences of African language speakers can be theorized, because Afrikaans became a “language of high culture, higher education and government” through the creation of such spaces by the apartheid system; the same cannot be said about the languages of black South Africans. Africans need to be given the space to theorize their own experiences using their own languages and cultural perspectives. As Herman Batibo argued, no developed country in the world over has achieved its development through the strength of a foreign language.

Before we start talking about English being an African language we should get our house in order first, by empowering ourselves through the empowerment of our languages, which in turn can empower Africans at a psychological level. You have not experienced pain and humiliation if you have not been educated through the medium of English in a rural school – I have seen a great many of my peers who were pushed out of the system, simply because they could not cope. Some do make it against all the odds, but are still looked down upon by English monolinguals who have never had to learn anything in a language that is not their mother tongue. Oh, I am well aware of the fact that language is not the only reason why students are failed or pushed out of the system, but language is one of those problems.

At the moment, English does not represent my experiences; it does not represent the experiences of many in the African continent. It is also true that there has been a shift in identities. Many in Africa have embraced English, but I argue that the majority of those who have happen to be a privileged minority, while rest need it to gain access to opportunities.

Rhodes Must Fall activists on 9 April 2015, the day the statue of Cecil Rhodes was removed from the University of Cape Town campus (photo by Desmond Bowles, via Wikimedia Commons)

English Unassailable but Unattainable

Thanks to colonialism, capitalism and neoliberalism, English is here to stay. English is the most dominant language in Africa and plays a big role in the world financial markets; which makes it impossible to ignore. This is why Neville Alexander argued that the power of the above mentioned factors make English unassailable in the continent, but at the same time English is unattainable for the majority, which is why he pushed for what he called a mother tongue based bilingual education for the South African education system in order to balance things out.

English also has to go through a contextual transformation from region to region all over the world. This is something that is already slowly happening, with English absorbing ways of speaking and terms from the contexts in which it is spoken. In South Africa, what is called South African English has had to adopt into its vocabulary words/concepts like “lobola” (a “gift” of cattle, nowadays cash to a bride’s family from the groom) because there is no equivalent English term (a “dowry” is the reverse of “lobola”). At the moment, very little about English is African, for as long as the British and Americans consider what they speak and only what they speak to be English, then English is still a long way from being an African language. For as long as I have to take a test to demonstrate my English competency to get into a British university, English is not and cannot be an African language. As Chinese investment makes inroads into the African continent, in South Africa the government – which does little for African languages – is pushing for Mandarin to be taught in public schools, when African languages are actually treated badly. Does this now mean in 50-100 years from now both English and Mandarin will be “African languages Ka Dupe”?

This post responds to recent articles in the Journal of African Cultural Studies:

- Mugane, J.: ‘Contemporary Conversations: is English an African language?‘ (2017).

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: ‘The politics of translation: notes towards an African language policy‘ (2017).

- Jeyifo, B.: ‘English is an African language – Ka Dupe! [for and against Ngũgĩ]‘ (2017)

The debate surrounding the use of English by writers of African literatures goes back to at least the 1960s. Prominent contributions to this debate include:

- Achebe, C.: ‘English and the African Writer‘ in Transition 18 (1965): 27-30.

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: Decolonising the mind: the politics of language in African literature (Heinemann Educational, 1986).

Alexander, N. 1999. English Unassailable but Unattainable; The Dilema of Language Policy in South African Education. PRAESA Occasional Paper. No 3. Cape Town.

Batibo, H. 2010. ‘The use of African languages for effective education at tertiary level.’ In Maseko, P. Terminology Development for the Intellectualisation of African Languages. PRAESA Occasional Paper. No 38. Cape Town.

Leave A Comment