Professor Francesca Orsini is the Principal Investigator of the MULOSIGE project, and leader of the North India case study. She is Professor of Hindi and South Asian Literature, as well as Chair of the CCLPS. Her research interests range from modern and contemporary Hindi literature to the multiligual history of literature in early modern North India

Mysteries of the Indian Jungle – Emilio Salgari’s Orientalist adventures

[The full text of this essay is published in: L’Inde et l’Italie: Rencontres intellectuelles, politiques et artistiques, eds. Marie Fourcade, Claude Markovitz, and Tiziana Leucci, Paris: Editions EHESS (Collection Purushartha, 35), 2018.]

“Soy antiimperialista por Sandokán y no por Lenin, soy feminista por el Capitán Tormenta, y simpatizo con los zapatistas por Flor de Perlas, la guerrillera filipina” -Paco Ignacio Taibo II. [1]

No Italian writer has left a deeper and more lasting imprint over Italian readers of a certain exotic image of India than Emilio Salgari (1862-1922). His adventure books spanning four continents rank among the classics of adventure/children’s literature. Indeed, were popularity alone determined membership to world literature, Salgari would count as the foremost Italian writer in the world.[2] Translated into French, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Polish, Russian, Czech, Hungarian, Dutch, and so on already at the turn of the twentieth century, he was read avidly as far as Latin America by readers such as Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, Che Guevara, Alejo Carpentier and Carlos Fuentes (though not in India as far as I know). His particular combination of detailed information and breathless adventure created great ignorance as well as a feeling of great familiarity, even intimacy for his heroes and locales.

Photographic portrait of Emilio Salgari. Courtesy Wikimedia commons.

Salgari belongs to the great season of adventure/juvenile literature that accompanied the age of imperial expansion and exploration aided by technological advances like steamboats and railways, as well as the proliferation of illustrated travel magazines and travel accounts for mass readership. (One of his main sources was the Giornale illustrato dei viaggi e delle avventure per terra e per mare, Milano: Sonzogno, 1878-). He set his over 80 adventure novels in places as far flung as nineteenth-century India and Malaysia, eighteenth-century pirates in the Caribbean, contemporary North and East Africa, the North American “Far West”, the crusaders in the Holy Land, among arctic and even interplanetary explorers — without ever travelling outside his native Italy, only as far as his local library. In fact, he’s probably the only novelist to have written about all the three regions of our project!

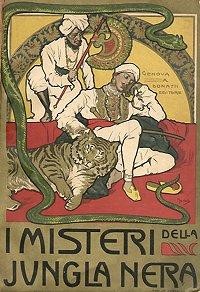

Original cover for The Mystery of the Black Jungle published by Antonio Donath, Genoa, in 1895. Courtesy Wikimedia commons.

Salgari’s most popular cycle fused together two separate narratives – the struggles and adventures of former Borneo prince and fearsome Malaysian pirate Sandokan, also known as the “Tiger of Malaysia” (and his followers called tigrotti, tiger cubs) and his friend, Portuguese adventurer Yanez de Gomera, and those of the Bengali snake-catcher Tremal Naik, loyal Maratha servant Kammamuri, and tame tiger Darma (Dharma?).

Critical writing on Salgari oscillates between ironic deconstruction (e.g. Umberto Eco’s Apocalittici e integrati, 1964) and more or less passionate apology by former fan readers, who point out that his heroes are usually pirates, outlaws, rebels, “brigands” fighting to right wrongs and defend their own and other people’s freedom against greater powers. Unlike Kipling or Rider Haggard, then, Salgari was no apologist of the British empire and its civilizing mission. In fact, anti-British sentiments and critiques are voiced by a number of characters in the Indo-Malaysian novels. “You are horrified of Thugs?”, Suyodhana asks Tremal Naik in I misteri della giungla nera (The Mysteries of the Black Jungle), “Because they strangle people? Europeans crushed us with the iron of the cannons, and we crush them with our snare, the weapon of our powerful goddess” (315).[3] Thrown out of Mompracem, Sandokan does not hesitate to formally declare war on Britain itself so as to teach “that bully, John Bull” a lesson (Il re del mare, 81).

We Sandokan, nicknamed the Malaysian Tiger, former prince of Kini Ballon, and Yanez de Gomera, legitimate owners of the island of Mompracem, notify the governor of Labuan that from today we declare war on England, the rajah of Sarawack, and their protégé.

From the ship Il re del mare, 24 May 1868

Sandokan and Yanez de Gomera (Il re del mare, 81).

Freedom and revenge are here combined: with the one single war steamship he has bought, Sandokan aims to disrupt British commercial interests and transatlantic routes, well aware that it is an unequal struggle and he will probably be defeated—defeated but in fact not destroyed. Defeat, like victory, is always temporary so as to pave the way for further adventures.

Salgari’s descriptions of his Asian heroes—Sandokan, Tremal Naik, and their allies—are engraved in the minds of generations of readers. Friendship and loyalty cut through ethnic and racial divisions: the Maratha Kammamuri is devoted to the Bengali Tremal Naik, Yanez and Sandokan are “like gods” for their tigrotti. The same is true of Salgari’s romances, all successful and happy (if mostly short-lived) inter-racial loves: between the British Ada Corishant and the Bengali Tremal Naik; between their mixed-race daughter Darma and the mixed-race son of Suyodhana; between the Malaysian Sandokan and the Anglo-Italian Marianna Guillonk; and between the Assamese princess Surama and the Portuguese Yanez.

Yet ethnic clichés abound. The same Dayaks who are praised for their beauty and prowess become “savages” (6, 8, etc.), “damned savages” (17) who “deserve no pity” (15), “bloodthirsty barbarians” (12), “idiotic fanatics” (27) who have been brainwashed and radicalized (“fanatizzati”) when they turn against Tremal Naik’s “civilizing” farms in Borneo. The first novel of the Indo-Malaysian the cycle features thugs as fanatic devotees of the goddess Kali who kill victims with their famous snare and offer them to her as human sacrifices in their opulent underground temple in the Sundarbans! Religious ascetics and thugs merge in a single and pervasive network of criminal, bloodthirsty and immensely rich fanatics who reappear in the various novels.

Can Orientalist fantasies really be anticolonial? Salgari was definitely a libertarian in the Italian tradition of the Risorgimento. Yet he was not outside the episteme of his times, which viewed Europe as more advanced than Asia and did not question the dominance of European empires. His pervasive reliance on orientalist and racial stereotypes reinforced feelings of cultural difference, superiority, and non-coevalness (Fabian).

At the same time, if we acknowledge that melodramatic narratives like Salgari’s are typically segmented and based on the mobilization of strong affects and stark moral oppositions that can however be mapped onto different, even contradictory stances, and that melodramatic characters also work on the basis of this segmented logic,[4] then anti-colonial utterances and postures are utterly compatible with orientalist and racist views. Salgari’s Latin American readers chose to read his novels as subversive of colonialism. The Spanish-Mexican writer and activist Paco Ignacio Taibo II, who claims Salgari as an inspiration, has even written new Sandokan adventures. His recent novel El Retorno de los Tigres de Malasia (2010) adds explicit anti-colonial consciousness to what he perceived to be Salgari’s implicit libertarian drive.[5]

Other readers, though, may be more riled by the pervasive traces of orientalist clichés.

Notes

[1]Paco Ignacio Taibo II : Soy antiimperialista por Sandokán”, El Comercio, 27 de October de 2010; http://www.elcomercio.com/tendencias/cultura/paco-ignacio-taibo-ii-antiimperialista.html. Accessed on 5 January 2018.

[2] In the 1980s, his Sandokan series underwent a new wave of popularity thanks to the TV serial starring the Indian actor Kabir Bedi. Informal enquiries with friends in India suggest that it is only through the refracted popularity of Kabir Bedi that Indians are faintly aware of Sandokan, and even then only as a TV series rather than an adventure novel; see e.g. “Birthday Special: 10 Things You May Not Know About Kabir Bedi”, Mid-day, 16 January 2016.

https://www.mid-day.com/articles/birthday-special-10-things-you-may-not-know-about-kabir-bedi/15918161. Accessed on 5 January 2018.

[3] In the novel Bloodslaughters of the Philipines (1897), Salgari dramatizes the very recent 1896 rebellion against Spain and condemns Spanish repression, whereas in The captain of Yucatan, he takes the side of Spain against the US. Ann Lawson Lucas’s research has also unearthed the critical history of his appropriation during Fascism when, decades after his death, he was championed as a writer of action, a “pre-Fascist” writer, and a fierce critic of Britain (Lawson Lucas 160).

[4] Typically, in the case of adventure and love, a hero will be desperately and crazily in love with a heroine only to forget all about her for hundreds of pages—the “adventure hero” and “lover” being two aspects of a segmented character; see Kapur.

[5] Matteo Giancotti, “Le tigri (antimperialiste) di Salgari e i libri di Paco Ignacio Taibo II”, Corriere del Veneto, 25 January 2010, reviewing the Italian translation of the novel which, like the French one, carries the subtitle: More anti-imperialist than ever. http://corrieredelveneto.corriere.it/veneto/notizie/cultura_e_tempolibero/2011/25-gennaio-2011/tigri-antimperialiste-salgari-libri-paco-ignacio-taibo-ii-181324859682.shtml Accessed 5 January 2018/

References

I miei volumi corrono trionfanti: atti del 1. Convegno internazionale sulla fortuna di Salgari all’estero. Torino, Palazzo Barolo, 11 novembre 2003, ed. by Eliana Pollone, Simona Re Fiorentin, Pompeo Vagliani. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, 2005.

Lawson Lucas, Ann. 2012. ‘La fortuna di Salgari: tra propaganda fascista e popolarità postbellica’, in La geografia immaginaria di Emilio Salgari, ed. by Arnaldo Di Benedetto. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 153-168.

Marazzini, Claudio. 2012. ‘Progettazione, invenzione narrativa, esotismi’, in La geografia immaginaria di Emilio Salgari, ed. by Arnaldo Di Benedetto. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 53-76.

Marchi, Paolo. 2012. ‘L’universo geografico di Salgari’, in La geografia immaginaria di Emilio Salgari, ed. by Arnaldo Di Benedetto. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 33-52.

Pozzo, Felice. 2012. ‘Il ciclo indo-malese’, in La geografia immaginaria di Emilio Salgari, ed. by Arnaldo Di Benedetto. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 77-102.

Salgari, Emilio. 1973 [1907]. Alla conquista di un impero. Milano: Garzanti.

Salgari, Emilio. 1969 [1895]. I misteri della giugnla nera. Milano: Mursia.

Salgari, Emilio. 1968 [1906]. Il re del mare. Milano: Fratelli Fabbri editori.

Spagnol, Mario. 1969. Il primo ciclo della giungla. Milano: Mondadori.

Torri, Michelguglielmo. 2012. ‘L’India e gli indiani nell’opera di Emilio Salgari’, in Riletture salgariane, ed. by Paola I. Galli Mastronardi and M.G. Dionisi. Pesaro: Metauro Edizioni, pp. 31-66.

Tropea, Marco. 2012. ‘Dalla parte dei ribelli” L’ideologia anticoloniale di Salgari’, in La geografia immaginaria di Emilio Salgari, ed. by Arnaldo Di Benedetto. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 137-152.

Leave A Comment