Annie Webster is a PhD student at SOAS, University of London. Her doctoral research explores corporeal motifs in post-2003 Iraqi fiction and is funded by the Wolfson Foundation.

You can follow her on Academia.edu, or on Twitter.

‘The Reality and the Record’ is the first tale in The Madman of Freedom Square (2009), a collection of short stories by Iraqi author Hassan Blasim. In this opening short story, an unnamed Iraqi asylum seeker recounts his traumatic experiences of war, kidnapping and torture to an immigration officer at a refugee reception centre in Sweden. As its title implies, the story explores the boundaries between fact and fiction, exposing the ways in which refugees necessarily move between the two in an asylum-seeking process that requires them to curate a compelling and convincing tale of political persecution in order to be granted asylum.

The story relays the refugee’s narrative in his own words. Yet it opens with a peritextual statement, distinguished from the main body of the text by italics, stating:

Everyone staying at the refugee reception centre has two stories – the real one and the one for the record. The stories for the record are the ones the new refugees tell to obtain the right to humanitarian asylum, written down in the immigration department and preserved in their private files. The real stories remain locked in the hearts of the refugees, for them to mull over in complete secrecy. That’s not to say it’s easy to tell the two stories apart. They merge and it becomes impossible to distinguish them.

Traditional Arabic stories begin with the phrase ‘kan ya makan…’, which is often equated to the English ‘once upon a time’, but can also be translated as ‘there was, and there was not.’ ‘The Reality and the Record’ confronts readers with a provocative reinvention of this traditional narrative opening: before readers are exposed to the asylum seeker’s story, they are warned that it might not be wholly true. Blasim brings the ancient narratological tension between fact and fiction into the contemporary world by critically reflecting on the truthfulness of tales told by asylum seekers in the twenty-first century. For refugees and asylum seekers confronting the legal system, the telling of tales ceases to be a recreational act, and becomes instead a performative utterance that can have real humanitarian consequences.

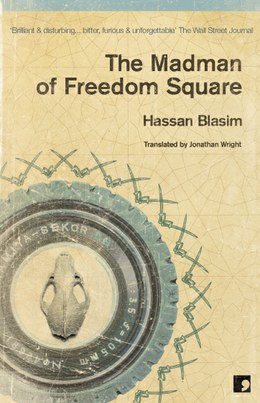

Cover of Hassan Blasim’s ‘The Madman of Freedom Square’

In the case of ‘The Reality and the Record’, the nameless refugee describes how he was kidnapped while working as an ambulance driver during the Iraq War and how he was kept in captivity for a year and a half, during which he was forced to film a variety of political videos playing the role of an Iraqi army officer, a member of the Mehdi army, a Kurdish fighter, a Christian, a Saudi terrorist, a Spanish soldier and an Afghan fighter before he was released and fled Iraq. His narrative is filled with violent episodes, descriptions of mutilated bodies and morbid reflections on the shifting kaleidoscopic politics of post-2003 Baghdad. Some of these elements, for example six decapitated heads that the narrator encounters at the beginning of his story and again at the end, are so grotesque that it is difficult to determine whether they are the products of nightmarish realities in post-2003 Iraq, or a disturbed mind.

As the man tells his tale, he reflects on how precarious his act of storytelling is, with comments such as: ‘I don’t know exactly what details of my story matter to you, for me to get the right of asylum in your country’ or, ‘If I go on like this, I think my story will never end, and I’m worried you’ll say what others have said about my story. So I think it would be best if I summarise the story for you, rather than have you accuse me of making it up.’ The narrator is acutely aware that his story seems impossible, begging his audience to suspend their disbelief. The use of the second person in these comments directs his narrative not only to an immigration officer – who we have been told is the implied audience for the story – but also to readers who are aligned with the role of immigration officer in their attempt to decipher what components of the story are true. Readers continue to occupy this role throughout The Madman of Freedom Square as they encounter a spectrum of stories describing the experiences of other refugees.

The story ends with another italicised peritextual statement, informing readers that:

Three days after this story was filed away in the records of the immigration department, they took the man who told it to the psychiatric hospital. Before the doctor could start asking him about his childhood memories, the ambulance driver summed up his real story in four words: ‘I want to sleep.’

The refugee’s story is dismissed as madness – the liminal territory between fact and fiction – and its narrator incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital.

Blasim’s narratives offer important, timely reflections on the movement of people and their stories in the contemporary world. They also indicate the commodification of migrants’ stories, standing as evidence of the ways in which refugee narratives have become a critical currency not only in migration politics but also in the market of world literature. As a migrant himself, Blasim has not only told a narrative sufficiently convincing to gain refuge in Finland, he has written a stream of compelling stories that have been published, widely translated and won literary acclaim. His writing contributes towards a growing body of migrant literature that traces the journeys, experiences, hopes and traumas of displaced people. As ‘The Reality and the Record’ suggests, Blasim’s stories – like those of many other migrants – are not derived wholly from reality, nor are they produced solely for the record. His writing occupies a precarious position between history and imagination, autobiography and projection.

As ‘kan ya makan’ implies, Blasim’s stories are and they are not: they impress upon readers the porous boundaries between fact and fiction, particularly at a juncture when tales of migration are gaining political and literary attention. Blasim and his characters have had to tell a story and hope that this is the ‘right story’ as judged by an asylum officer, readers of ‘world literature’, or both. While Blasim’s stories have received international praise, and have been translated into 23 languages (see: around the world in Blasim covers), the original Arabic stories have been banned in several countries in the Arab World, proving that the ‘right story’ might enable a migrant to travel across boundaries but the story itself might not necessarily be able to travel unhindered.

More recently, Blasim edited and contributed towards Iraq+100 (2016), a collection of short stories by ten authors of Iraqi origin imagining their homeland one hundred years after the 2003 invasion. Hailed as the first example of Iraqi science fiction, the collection offers a spectrum of dystopian, optimistic and fantastic depictions of Iraq in the future. Blasim’s own contribution, ‘The Gardens of Babylon’, imagines a future writer in Iraq plundering the country’s rich literary heritage to create ‘story-games’, a new mode of storytelling whereby narratives based in a virtual reality would have the potential to blur the boundaries between reality and the record even further.

Both ‘The Madman of Freedom Square‘ and ‘Iraq+100‘ are available in English from Comma Press, along with other works by Hassan Blasim.

Leave A Comment