.

In the medieval period, the Christian and Muslim parts of the Horn of Africa were well connected with centres of religious learning in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, with a vast network of exchanges and translations between Geez, Arabic, Greek, Coptic, and Syriac. Mission stations set up by various European denominations in the 19th century coincided with a rapid increase in the volume of Tigrinya- and Oromo-language production, while in the imperial court Amharic gradually replaced Geez as the official language of the state.

From the beginning of the twentieth century Amharic saw a boom in fictional and non-fictional production, mostly linked to new state schools, newspapers, and publishing houses. The short-lived Italian colonial presence (1936-1941) did not significantly impact Amharic literary forms, styles and aesthetic values. Starting from the 1941 liberation, policies of cultural assimilationism reinforced the marginalisation of Ethiopian languages other than Amharic, such as Tigrinya and Oromo. International scholars have tended to reinforce the power relation between Amharic as the cultural centre of the region and “peripheral” literatures—thus allying themselves with the dominant language.

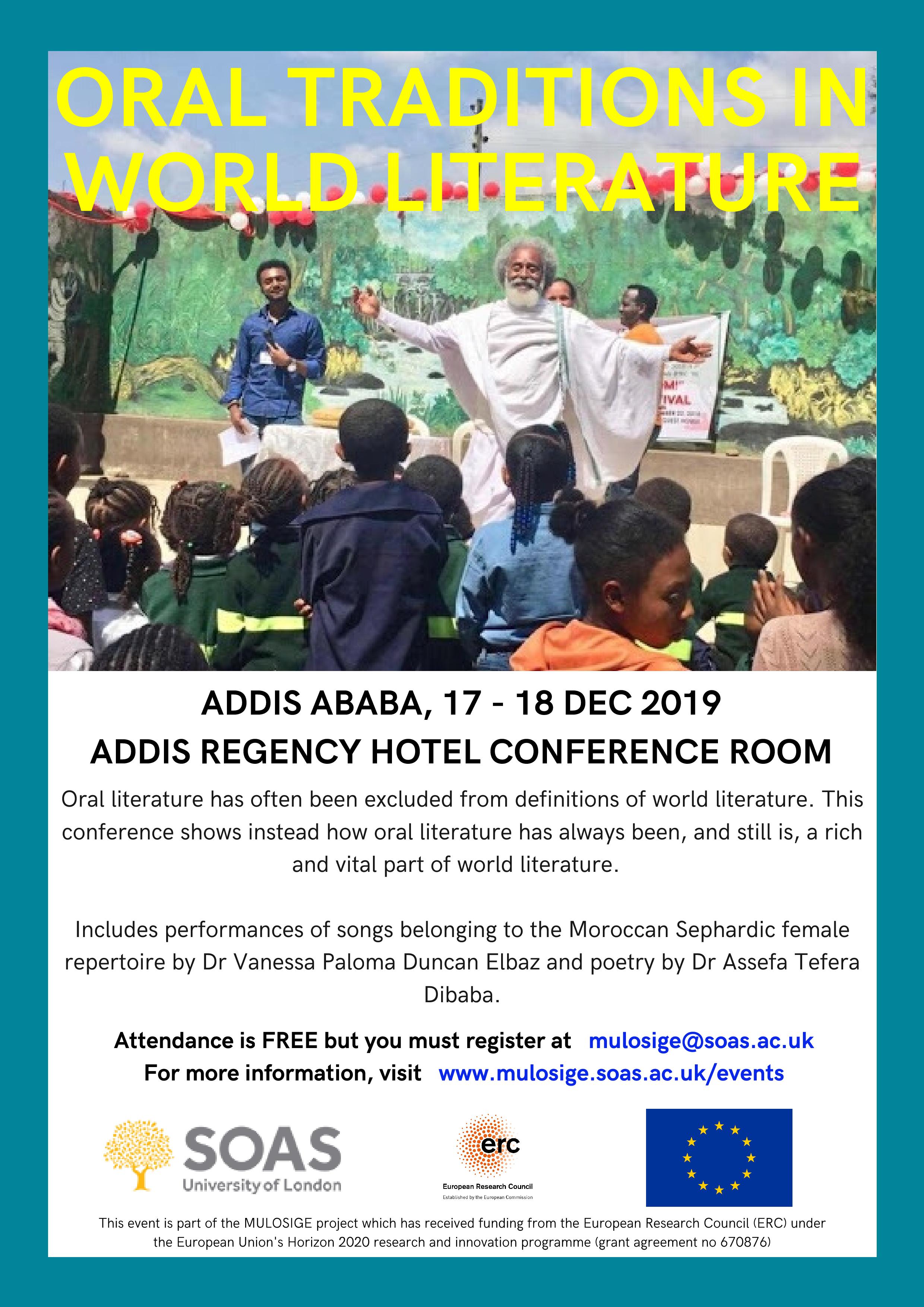

Although the issue of orality is perceived to be central to the literary and cultural heritage of the Horn of Africa, there is a general lack of comparative studies between the oral and the written and their interactions. MULOSIGE’s comparative focus on orature and written genres will show how the “local” in the Horn of Africa is layered and structured along networks of linguistic, cultural and political power relations.

Farewell has colors: Adam Reta’s “Colors of Adios”

In his latest Amharic novel, the Ethiopian writer Adam Reta uses the metaphor of light prisms and colours to describe how couples, histories and nations part, mix and combine

Why do we read so few translations?

Statistics show that only between 3 - 5% of literary books published in the UK are translations. Ann Morgan in A Year of Reading the World writes about the difficulty in finding out about and getting hold of translations, even in the age of global publishing.