Ayele Kebede Roba is an MPhil/PhD researcher. He works on Ethiopian literatures with particular emphasis on the comparative study of Afaan Oromoo [Oromo] and Amarinya [Amharic] contemporary novels.

The Ethiopian Writers’ Association; Between Multilingual Openings and Monolingual Practice

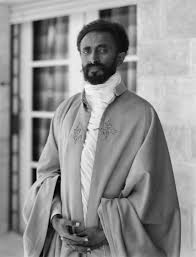

Emperor Haile Selassie introduced monolingual language policies

The Ethiopian Writers’ Association (EWA) was founded in 1960 by a group of writers and patrons of Amharic literary writing. The founders expressed their ardent passion for such an association in a firm statement: “We, Ethiopians, who the love of literature dwelt upon us, founded this writing association in order to improve and promote literary writing” (cited in Dereje 2011: 10). The main reason why the association was needed, as stated in a book published a year after the establishment of the association, was to help “the authors who are rich in knowledge, but have no finances” (p.11). This financial hurdle has continued to haunt the association to date. In the 2011 magazine celebrating the 50th anniversary of the association, Dereje Gebre claims that the association has not received a sufficient support from the Ethiopian government since the time of its inception. From 1960- 1975, the association used to be occasionally supported by the “good will” of Emperor Haile Sellassie and by the one-off donations of the publishing houses in Ethiopia. Nevertheless, from the very beginning of its establishment, the main source of finance has been the contribution made by the members of the association and the patrons of Amharic literary development. The first work published with such contributions back in the 1960s was a book by Mengistu Lemma which introduces the techniques of theatrical writings.

Though the founders and the administrators claimed that the association was an independent body, the EWA did not escape the influence of the state’s assimilationist language policy. This policy was Ethiopia’s first official language policy, promulgated through a decree by Emperor Haile Selassie in 1944. The decree prohibited the public use of any language other than Amharic including in schools, courts, and official state institutions. It was also prohibited to publish in other languages. Amharic became “the sole national language of the empire and all other languages were suppressed” (Mekuria 1994: 99). It was, at the time just like nowadays, the mother tongue of a considerable part of the Ethiopian population, but not a majority. This monolingual language policy was later incorporated into the revised constitution of the Haile Sellassie government in 1955. The Emperor undertook a series of additional measures to promote Amharic language. He introduced the Haile Sellassie I prize for Amharic literature in the 1960s to encourage Amharic writers (Degineh 2015), and established a national academy devoted to the study of Amharic literature in 1972 (Mekuria 1994, 1997; Mohammed 2008).

The founding charter of the EWA reflected Emperor Haile Sellassie language policy. This is openly stated in the EWA’s founding charter, which lists the association’s main objectives as:

(a) “በኢትዮጵያ ለድርሰት መስፋፋት አይነተኛ መሳሪያ ለሆነው ለአማርኛ መሞዋላት የቻለዉን ማድረግ።” “To work tirelessly in order to develop the necessary facilities for Amharic, which has been a typical vehicle for the expansion of Ethiopian literature”.

(b) “በአማርኛ የሚደረሱ ወይም የሚዘጋጁ መፅሃፍት በሚታተሙበት ጊዜ በተቻለ ረገድ ሁሉ መርዳት።” “To selflessly assist in all possible ways the publication of the books authored or prepared in Amharic” (quoted in Dereje 2011:10).

According to Dereje (2011), during the government of the Dergue and Mengistu Hailemariam (1974-1991), the association used to receive a financial support from the government and was able to open branch offices in some regional towns. Some other organizations also helped the authors with publication works during this time though the names of those organisations are not mentioned in Dereje’s essay.

After the 1991 restructuring of the Ethiopian state along ethno-federal lines, all languages in the country received constitutional recognition. The government allowed the speakers of different languages to use and write in their languages within their local and regional contexts, but Amharic continued to serve as the only federal working language. According to information I collected from the association’s manager during my 2018 fieldwork, following the fall of the Mengistu’s government in 1991, all the benefits that the association used to get from the government stopped. The new government of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) has so far ignored the association. To mention the best example, it is in a very recent time that the association has been able to get a plot of land where to build its head office in the capital after a long period of repeated request. Regardless of all these funding and logistical challenges, the association continues to function thanks to the assistance it has been receiving from its members and donations from individuals and publishing houses. The effort to promote the literary works of the young writers also continued, though not on a regular base. For example, on its 50th anniversary, the association published eight new books through a big funding grant it received from the Artistic Printing Enterprise (Tadele Gedle, 2011).

During the Haile Selassie’s government, the EWA only operated in Amharic because it could not afford to publicly violate the monolingual government policy. But it did continue to embrace the assimilationist policy to date, even after the EPRDF lifted the restrictions against publishing in other Ethiopian languages. Following the post-1991 language policy reform, the EWA came up with a new charter and revised objectives. Two of these objectives worth mentioning:

(1) “ማህበሩ ከማንኛዉም የፖሎቲካ፣ ሃይማኖት፣ የዘር፣ የቋንቋ፣ የፆታ ተፅዕኖ ነፃ ሆኖ ለሙያተኞች መብት እና ጥቅም ማዋል።” “To protect and benefit the rights of professionals without the influence of politics, religion, ethnicity, language and gender”.

(2) “የሃገሪቱ ስነ ጽሁፍ እንዲስፋፋ፣ እንዲዳብርና እንዲበለፅግ፣ የህብረተሰቡም ስነ ጥበባዊ ፍላጎት እንዲረካ አመቺ ሁኔታን ይፈጥራል።” “To create a situation conducive to the expansion, development and prosperity of literature in the country in order to satisfy the society’s need for literature” (quoted in Dereje 2011:11).

The principles listed here are important in their own right and this multilingual approach should be encouraged. However, the practice of the EWA seems to go against its stated objectives.

An example of this is reflected in the literary magazine, Bilen, run and administered by the association. Regardless of its claim to be open for non-Amharic speakers, Bilen, in practice, is found to be a platform where only Amharic writers and readers publish their works and exchange their views and experiences about issues in Amharic literature. This is also evidenced in its editorial policy, which is inhibiting the literatures in Ethiopian languages other than Amharic:

(1) “የመፅሔቱ መደበኛ የፅሁፍ ቋንቋ አማርኛ ነው። ሆኖም አስፈላጊ ሲሆን በእንግሊዚኛ የተዘጋጁ ፅሁፎች ልያትም ይችላል።” (“The regular writing language of the magazine is Amharic. Whenever it is deemed necessary, writings in English can be published”.

(2) “ጥራታቸው የተጠበቁ ፅሁፎች ከተገኙ እንደሁኔታዉ በለሎች የእትዮጵያ ቋንቋዎች በልዩ እትም መልክ በተጋባዥ አዘጋጆች (ገስት ኤዲተርስ) አማካይነት ሊታተም ይችላል።” “If the works of good quality are found in other Ethiopian languages, they can be published in a special issue through the assistance of the guest editors and this is subjected to a condition” (Bilen, 2017: 92).

On the one hand, the editorial policy de facto imposes writing in Amharic, as it does not encourage the publication of writings in languages other than Amharic. On the other hand, it stresses the “quality” of the works in other Ethiopian languages as a requirement for publishing, although it does not specify according to which criteria the “quality” of a submission is assessed. The policy does not explicitly state quality requirements for the writers who publish in Amharic or English. The bureaucracy also seems complicated, as publishing in non-Amharic languages is contemplated only in the form of a special issue with guest editors. There is an ambiguous phrase that states “አንደሁኔታው” means “subjected to a condition” but no condition is explicitly stated at all in this policy. Such an ambivalent statement made me sceptical of the practicality of the editorial policy as far as non-Amharic writings are concerned. Moreover, during my survey of most of the published volumes of Bilen, I found out that all works in the volumes are presented entirely in Amharic and therefore intended for Amharic readers. And if we look at the general track record of the association itself, the theoretical commitment to multilingualism did not translate in any concrete result. The EWA has published only one non-Amharic novel in more than half a century of its existence.

All in all, I do not believe that it is a problem for Amharic literature to have a literary magazine of its own. Amharic writers have the right to target the speakers of their language through dedicated organisations and publications. Nevertheless, when the association that claims to be “Ethiopian” restricts its policy and publications to the tradition of one language and presents that language as a representative of the country, the legitimacy of such a claim should be called into question. It is paradoxical and self-contradictory for the EWA to aspire to be “Ethiopian” while its main publication is devoted exclusively to Amharic literary tradition and Amharic readers. It also is reductive and limiting to reduce Ethiopian literature only to the Amharic literary experience. In conclusion, the EWA seems to recognise multilingualism in theory, but not in practice. Therefore, it is my strong assertion that the association should reconsider its practice and adopt the policies of other literary journals such as Lotus and African Literature Today, where the publication in more than one language is encouraged both in theory and practice.

Leave A Comment