Simon Leese translates Lamaḥāt min al-adab al-Hindī al-ḥadīth by Muhammad Fikri (al-Thaqāfah 43, 12th May 1964: 25-27). The original essay can be found at the Alsharekh.org archive.

Glimpses into Modern Indian Literature

Written by Muhammad Fikri, translated by Simon Leese.

Image from Unsplash.

The first thing that comes to mind when one hears the word “India” is that beguiling eastern land awash with metaphysical truths and spirituality. At least this is what people are familiar with from reading the poetry and tales of ancient Indian literature they have access to. They also get this impression from watching Americans movies, which are above all concerned with depicting the people of India as naïve and backwards, distracted from the demands of contemporary life by naïve spiritual and metaphysical matters.

It is an indisputable fact is that Indian civilisation and culture are built on these spiritual and metaphysical systems of thought. Indeed, most of India’s philosophical and religious traditions, including Buddhism, Hinduism, and Brahmanism, celebrate them. According to these traditions, a truly content person is one who is able to escape the vicissitudes of the body to reach the world of pure spirit.

But colonialism has attempted to efface and even wage a tireless war against another fact: that India – like the whole eastern world – has witnessed a great awakening and begun to come to terms with its own ancient literary heritage. It has cast aside all the metaphysical ideas and naïve spiritualities that have proved to be stumbling blocks on the path towards progress. By taking what it needs from these ideas, and responding to the realities and demands of modern Indian life, it has ensured that the wheels of progress continue to move forwards.

This is what has come to pass in recent years. Developing countries have all risen up to shake off the dust of the middle ages, which has weighed them down for generations. The people have come to know their truth and the truth of their existence in this world. With all the power and fortitude they possess, they have begun to rise up against colonialism, exploitation, and the terrorist apparatus. And to do so they have employed all the intellectual, artistic, and revolutionary means available to them.

Literature is a mirror that reflects civilisations of people around the world and how those civilisations develop. Literature is also what propels people along the path of progress and liberation. We can glimpse the stages of this development in Indian literature.

However, it was only in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that India came to know literature in its modern sense as represented by the play, the short story and the novel. This occurred through contact with European and in particularly English culture during the colonisation of India. It is true that India had epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata, both of which began to emerge during the lifetime of Jesus. They tell stories that closely resemble the novel form. The stories of the Panchatantra and tales of the Hitopadesha contain within them the essence of the novel. The love tales of Govinda [Krishna] [1] and the literary heritage of the middle ages are also almost novelistic. However, they are rather different from the conventions and forms of the novel and short story in the modern period, which developed in Western Europe as a result of the industrial revolution and which brought about a shift in modes of thought from religious metaphysics and doctrinal ethics to social and psychological analysis.

Through its contact with Western culture, India inevitably felt the influence of new forms of modern art. The novelist and critic Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, considered one of the greatest authors of modern Indian literature in Bengal alongside Tagore, made the first attempt to represent Indian life in the modern artistic form, influenced by the novels of Sir Walter Scott. His artistic vision drew from aspects of Indian life at a time when it fell under the influence of British political and economic control.

This can be seen in his depiction of the revolt of Muslim peasants against feudalism during Lord William Bentinck’s governorship of Bengal. His motivation in doing so was to depict the metaphysical truth of Indian society. Nevertheless, his artistic capabilities remained limited due to his inability to understand the modern novel as it was in the West.

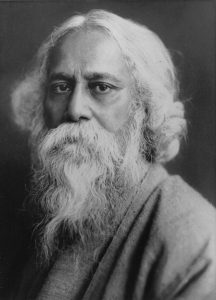

Rabindranath Tagore, Wikimedia Commons.

The second attempt was made by Rabindranath Tagore, a distinguished young man belonging to the aristocracy and the son and heir of a large family of landowners. He travelled to England to study law, but legal studies could not satisfy his sensitive art-loving soul. He soon travelled back to his country to write in its journals and raise the level of intellectual and social life there, establishing a school of art concerned with spiritual, human and social values. With great creativity and skill, this young man wrote in all artforms, including poetry, plays, novels. He fully deserved the worldwide recognition he achieved for his genius, and in 1913 he won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Tagore believed that the need for blending Indian values with European post-enlightenment values was as pressing as the need to properly understand the new short story form. He had read Turgenev and Tolstoy as well as French writers who came after and were influenced by Flaubert. Like Tolstoy, Tagore considered the short story to be a dramatic representation of internal transformations experienced by the self across time and place.

Interestingly, despite being influenced by ancient Sanskrit poetic forms, Tagore adopted the modern novel to best suit [the needs of] the new society around in. Bankim had merely been a narrator and moraliser who would begin by saying, “I am telling you this story, dear reader, so that you may avoid the sorry error of Krishnakanta.” Tagore, on the other hand, developed characters who were independent of the writer and who seemed to live real lives, even if some aspects of those lives represented some moral truth. Because of this, they left an impression in the minds of readers and entered their unconscious.

Cover of “The Wreck”, a novel by Rabindranath Tagore. Wikimedia Commons.

“Shipwreck” is a novel that tells the story of a young, well-educated man called Ramesh Babu. After he graduates as a lawyer, his father wishes to marry him off to a young woman he has never seen before. Ramesh is in love with another young woman named Hemnalini and she loves him back. All the same, Ramesh submits to his father’s will and marries the other woman in her remote village without even seeing her first. While the marriage procession is returning by boat along the river, a fierce storm breaks out destroying everything. Ramesh wakes up to find himself on a sandy shore next to a beautiful young woman called Suryamani [Sarimani?] Kamala. He assumes her to be his wife at first, but he later realises that she is the wife of another man that she had also never seen before. Kamala therefore assumes that Ramesh is her husband.

Although Ramesh Babu allows Kamala to keep believing this, he treats her like a sister rather than entering into a relationship with her. He travels widely with her and together they come up against a series of strange coincidences. The fates toy with them until Ramesh final finds Kamala’s husband for her. Ramesh, meanwhile, returns to his own beloved Hemnalini.

During their journey, Tagore show us many different aspects of Indian life as well as the country’s customs and philosophies.

Tagore’s “Shipwreck” is considered an expression of the contradictions between old and new values that had arisen in Indian society, the most obvious of which existed between older ideas of marriage and marriage that was built upon spiritual partnership. He presented all of this in a new artistic form that Indian literature had never seen before, even if he remained faithful to the traditional structure of beginning, middle and end at a time when the classical short story was becoming more poetic in form.

Tagore paid this trend no attention in his later novel “The Home and the World” and he was unable to make further progress before his death in 1941.

A rift in artistic form had opened up in Indian Literature that those after Tagore were unable to close. Sarat Chatterjee took the novelistic technique back to the narrative style of Bankim. In their novels, the trio of Chatterjees [2] that came after–Tarasankar, Bibhuti and Manik – turned their attention to peasants and poor communities living in large cities, but were unable to reach the level of Tagore in terms of artistic form.

Some writers in India write in English alongside the numerous national languages to be found across India’s vast expanses. This has led some historians of Indian literature to write separate histories for each language. This division is not sustainable in Indian culture since, despite its many languages, it derives from a single civilisation.

Indian society has identified 14 [major] languages and categorised them into four major groups according to origin: Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Austric and Sino-Tibetan.

Hindi–a form of Indo-Aryan–is considered the most important of all these languages since 44% of the population speak it, and speakers of other Indo-Aryan languages such a Bengali, Assamese, Urdu and Marathi easily understand it.

Hindi therefore became the most suitable language to represent modern India and was proclaimed the state’s official language, although English has continued to be used for official business for the last fifteen years.

Those writing in English include Mulk Raj Anand, Raja Rao, R. K. Narayan, Bhabani Bhattacharya and other writers who are considered bridges between India and the West. The publication of their novels in the West has led them to pursue the most innovative modernist artistic techniques and to devise in their novels as many different characters and settings that the modern artistic form [of the novel] can sustain.

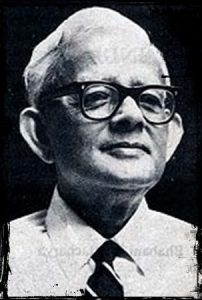

Bhabani Bhattacharya, Wikimedia Commons.

Bhabani Bhattacharya is considered one of India’s greatest contemporary writers. He wrote “So Many Hungers!” in 1947, the same year that India was liberated. The novel depicts the famine and national catastrophe that devastated Bengal, and the multitudes of anxious people slowly making their way to Calcutta by foot and, starved to death, falling at the side of the road. He masterfully depicts an Indian woman in her final moments when a jackal buries its fangs into her still-living body. Some think that Bhattacharya’s writing harks back to the kind of naturalism that describes merely for description’s sake but Bhattacharya had nothing to do with that movement. Bhattacharya was someone shaken by the suffering of his people and who raised up their voices to draw attention to the miseries caused by colonialism: a history that cannot be erased from the memories of any nation that has suffered the catastrophe of colonialism [3]. However atrocious these images are, they are not just powerful witnesses to the sufferings of the Indian people, but a frank accusation against colonialism everywhere today.

In his more recent novel “He Who Rides a Tiger”, Bhattacharya returns once again to the war years, although with a different style and characterisation. The story centres on an ordinary man among the people, a blacksmith named Kalo, who, in order to escape poverty, is forced by the exploitative colonial society in which he lives to adopt the same means of cheating and deception that society uses against him. Although he convinces himself that he has won his freedom and independence, he has in fact only adapted to the laws set down by an exploitative society and acquiesced to it. In order to become human again, he has to return to the people.

During the famine, Kalo is imprisoned for stealing two bananas. In prison, he learns his first political lessons from a young prisoner incarcerated by the exploiter class: “They only strike us because they fear us. All we have to do is pay them back twofold.”

Kalo represents the awakening of Bengal, which, during these years of terrible trial, brought forth a thousand years’ worth of resentment in raging waves that crashed against the colonisers, their regimes and henchmen, and against the lives of luxury and pomp that they drained dry from the strength of the Indian people.

By way of a daring deception involving the appearance of the diety Shiva, Kalo is able to make himself out to be a Brahmin priest and build a temple with the great wealth that had come his way. This in turn brings him even more money. Kalo’s daughter, however, suffers greatly from this life built on deceit and hypocrisy. After she threatens to leave him, he finally comes to his senses. The story reaches its dramatic climax in the final scenes during one of the temple festivals when Kalo tells the throngs of people the truth of his fake miracle. He accuses society of having compelled him to do what he did and then leaves the temple with his daughter.

The author was extremely successful in creating stark dramatic images of a man of the people. Kalo the blacksmith represents not only an archetypal Indian man under the yoke of colonialism; at the same time, he represents a living archetype of Indian literature.

Modern Indian poetry is, like the story, developing in two main trends. The first is the nationalist movement that stirs up love for liberation. The second trend is that of backwards looking people who are still chasing the closed-off world of philosophy and ancient beliefs, ignoring problems of the contemporary age.

Poets representing the first trend include Bharatendu Harishchandra, Maithili Sharan Gupt and Suryakant Tripathi Nirala.

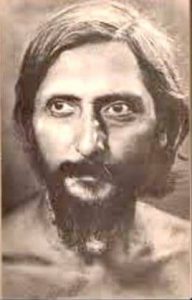

Suryakant Tripathi Nirala, Wikimedia Commons.

Nirala, born in 1866, is considered India’s greatest poet of the modern age. He began writing in the third decade of the twentieth century as a romantic poet influenced by the beauty of nature and believing that it holds a supreme power to lead subjugated peoples along the way to freedom and prosperity. He participated in a romantic movement deeply informed by humanistic principles. The poets of this school dealt with religious and philosophical subjects, and they contemplated ethics and humanistic beauty founded upon spiritual values.

They drew on symbols from to express these ideas; we can find such symbols in Nirala’s early writings. For this poet, dawn is a symbol for a new history of India; in the sound of thunder, he hears the sounds of the battle for freedom. The storm signifies the world’s renewal, and the flowing water in his poem “Gushing torrents” are the victory of newly awakened forces against colonialism and exploitation:

Clear the path ahead of obstacles;

This violent, gushing torrent

Is in the prime of youth.

Nobody can rein it in.

Today all obstacles have been cleared away

And the spirit is free once more.

Despair and tears have ceased;

Washed far away by the rushing currents.

Nirala’s powers of perception grew and he rose up to resist colonial and social oppression as well as defend women’s rights. He became deeply involved with the national liberation movement, which appears in his poetry as if reflected in a mirror; in Nirala’s poetry, natural forms don’t appear as mere images, but living manifestations of nature. While Nirala’s early poetry was full of hopes and dreams of a prosperous future for India, he also depicted India’s past greatness, as can be seen in his poems “Delhi” and “Ruins” and his series of poems about Jovind Singh who led the revolt by Punjabi peasants against the Mughal empire. Despite the often emotive and tear-inducing melancholy tone in Nirala’s poetry about the tortured soul’s unending and inconsolable suffering, we find that he does believe that life will triumph:

No, I don’t want to die now

So prematurely;

Now that the verdant spring

Has arrived in my garden.

I have only read the first line of my life

And an entire life awaits me.

What meaning can death hold, then?

There is only life, and life alone.

We even see Nirala retaining this deep faith when his only daughter died an invalid and poverty prevented him summoning a doctor or buying medicine for her. Grief cannot crush his resolve; in his poetic lament to mourn her death, “Remembering Saroj”, he says:

We must face the future with all our determination,

Destroying fate’s decrees.

Even in the darkest days of his life, he never tired of fighting colonialism and calling for the human right to a free and dignified life. It was this that led the writer Krishnadas to name him as the greatest modern poet of India in his book “Twelve Great Indian Poets”. “We have seen how Nirala can bend steel to his will,” Krishnadas writes, ”but we have never seen Nirala being diverted from his course, accepting defeat even for a moment, or underestimating his enemies.”

The Indian novel and Indian poetry continue to be pursued according to modern artistic techniques and forms. At the same time, they attempt to bring together ancient India and the modern India that has driven out colonialism to become a democratic republic. And they attempt to transform all the values, philosophies and principles left behind by colonialism that run in the veins and consciousness of the people in order to bring forth new values.

All of this offers lively and rich material for imaginative writers.

These images are available on an open usage licence. Read them in the original journal here.

Muhammad Fikri published a great deal with al-Thaqāfah and other Egyptian literary journals. He also published at least one collection of short stories and a play.

Statement about the journal in its first issue:

Egyptian weekly journal started in 1963 (Cairo). Editor in Chief Muḥammad Farīd Abū Jadīd.

You can explore the journal here.

This statement sets out the mission of the journal [paraphrase]: “to be a weekly journal where writers can come together to support ethical/spiritual values…to be a new pillar of the intellectual awakening (nahdah fikriyyah) in the Arab region…and be a vibrant meeting point between the varied cultures and branches of knowledge that we and others have, a cultural bridge that broadens our minds’ horizons, a window through which we can see what happens in the world around us, and a mirror to reflect our cultural revolution and other revolutionary cultures together.

…

Our slogan, upon which cultural planning in the United Arab Republic is built and which at the same time determines the mission of this journal, is that ‘Culture belongs to the people as a natural right and cultural feudalism has ended, never to return.”

An article called “Insights into world politics”

A translation of Luigi Pirandello’s The Jar.

A feature on television in the United Arab Republic and the world.

Leave A Comment