Simon Leese translates ‘This issue’ (editorial for special issue on Indian Literature) by ʿAlī ʿUqlah ʿUrsān (Ali Ukla Ursan) al-Ādāb al-ajnabīyah 54 and 55, Winter [1987] and Spring 1988: 3-8. The original essay can be found at the Alsharekh.org archive.

Editorial for special issue of ‘Foreign Literatures’ on Indian Literature

Written by Ali Ukla Ursan, translated by Simon Leese.

Arab Writers Union, current logo.

With this special issue on literature in India, the Arab Writers Union continues a journey it began with previous special issues of this same journal. These dedicated issues have turned their attention to literatures that have, for one reason or another, passed us by. They reflect our desire to learn more, enrich ourselves, and work towards greater constructive collaboration between our culture and others. We hope they will open a door to creative crosspollination between our literature and the literature of other countries so that we might attain a richer and more diverse understanding of human culture.

A special issue on literature in India is especially significant since it stems from a desire to reinvigorate ancient links between Arab culture and the cultures of India. These links came into being on a basis of mutual respect and trust. A special issue on Indian literature also serves to emphasise how important it is to know more about Indian culture, it’s literatures, and arts in the present day as well as finding out how they have developed throughout history. If we delve deep enough into this, we can bring these two cultures into constructive communication with each other. This issue also serves as a call to put an end to a situation that practically all literatures of the East have fallen victim to. Under the influence of western colonialism, an unequal binary has arisen where borrowing, imitation, and subordination prevail on one side, and hegemony and feelings of superiority prevail on the other. This binary opposition is between literatures of the east, and the literatures and culture of the colonialist west. It began during the period of direct colonial control, and it has continued since independence thorough technological supremacy and economic influence. Eastern countries have forgotten or neglected to nurture and consolidate the ancient links that have tied them together and benefited them all. They have also overlooked a whole history of contact. The diversity and richness enabled by living links between different literatures and cultures are hugely important. These links are built on respect, trust, talking together as equals, and sharing similar environments, as well as the interactions between different religious beliefs, peoples, and languages.

European colonialist culture has caused much harm to the cultures it as invaded. Britain had one of the most negative impacts in this regard. The “White Man’s Burden” that was claimed by the English colonialist poet Rudyard Kipling cost India a great deal, as it did other English colonies. Britain plundered archaeological treasures alongside natural riches, and offered up missionaries together with its artillery. At the same time that it appropriated the languages, ideas, beliefs and wisdom of the past, it undertook a process of westernising local customs, public life, and societal structures. If India had not been so geographically remote, Britain might have done what France attempted to do to Algeria: it would have claimed that India was part of its territory, snatched away briefly by the sea, but now happily returned to be to be encompassed by a halo of blue water.

East India House, Wikimedia Commons

Although European colonialism has cost the peoples of the East a great deal, it claims to have given them a lot. In the region of Calcutta, which was controlled by the East India Company, “30,000,000 of human beings were reduced to the utmost extremity,” in the words of Macaulay.

But dying of poverty and starvation was one of the great “benevolences” offered by British colonialism, a country that carried the burden of civilising “backwards peoples”! The British sent floods of missionaries alongside thieves who robbed Indians of their wealth, labour, and wellbeing. But after three centuries and because of the practices of Christians rather than Christianity itself, as Will Durant suggests, success came in the form of the most famous reform organisations to be influenced by the spirit of Christianity: the Brahmo Samaj. This organisation is [now] “extinct in Indian life.” [1] British Colonialism also succeed in making English an official language, and a language of literature and culture that could be read practically all over India. This did not mean, however, that it managed to hold back the influence of national languages. Nor did it eliminate them or undermine their status. There are six main contemporary languages that contain the treasures of authentic Indian culture. Each of these is a vehicle for the pride, enormous achievements, national spirit, and communal sentiment of its speakers. These languages are deeply musical and expressive. Alongside them are ancient languages that since time immemorial have been imbued with histories of suffering, philosophical thought, and the spirit of religious belief in India. By this I mean the great epics: the Mahabharata, the Bhagavad Gita, the Ramayana, and other fruits of individual and collective creativity that have constituted the main elements of culture in India. As Goethe said about one of these, the play Shakuntala by the fourth-century author Kalidasa:

Wouldst thou the young year’s blossoms, and the fruits of its decline,

And all by which the soul is charmed, enraptured, feasted, fed;

Wouldst thou the Earth and Heaven itself in one sole name combine?

I name thee, O Shakuntala! and all at once is said. [2]

The British colonialist cultural onslaught had a relatively limited impact on Brahamism. To a great extent, Brahmanism, which had absorbed Buddhism, held back the spread of Christian missionary activity and almost stopped it in its tracks. It had also come face to face with Islam, but the latter held its ground. Brahmanism continues to offer a great deal of intellectual vitality, prosperity, and fortune to India, which can be seen manifested in the country’s literary, intellectual, and political thinkers, personalities, and movements.

Without a doubt, India enjoys unique levels of towering ambition and tolerance together with a spirit of peace, a meditative ascetism, and an expansive view of the universe. This is because India’s people have given concrete form to cultural and religious interactions between Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam. There are wonderful indications of this creative interaction in Indian literature, and of the values and spirit it embodies to unify humankind with the aspirations and greater purposes shared by religious beliefs.

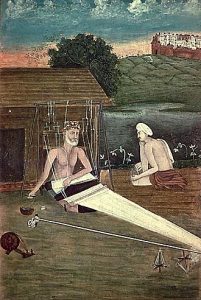

Picture of Kabir Weaving, Wikimedia Commons

We can find all of this in great personalities such as the inimitable poet Kabir and in his endeavours to bring Islam and Hinduism together in his view of life and people. When he died in Benares, followers of both religions claimed him as their own. Kabir gave voice to his thought and mission in his poetry and maxims:

O God, whether Allah or Rama, I live by thy name. Lifeless are the images of the gods; they cannot speak; I know it, for I have called out aloud to them. … What avails it to wash hour mouth, count your beads, bathe in holy streams, and how in temples, if, whilst you mutter your prayers or go on pilgrimage, deceitfulness is in your hearts? [3]

And we find it in Ram Mohan Roy, who strived to integrate Christianity and Hinduism, and proposed a “new religion, which should abandon polytheism, polygamy, cast, child marriage, suttee, and idolatry, and should worship one god – Brahman.” [4]

And we find it in the poet Rabindranath Tagore, who sang to the whole of India in the Bengali language. Because the English approved of him, his patriotism was called into question. But when he renounced the knighthood he had received from the English, these doubts were dispelled. He was critical of idolatry and harmful traditions, and called for a rejection of national chauvinism. He yearned for internationalism: “I am of an age with each; what matter if my hair turns grey?” [5]. Like his Child Angel, he never stopped pondering, shouting, chanting, and singing out:

They clamour and fight, they doubt and despair, they know no end to their wrangling.

Let your life come amongst them like a flame of light, my child, unflickering and pure, and delight them into silence.

They are cruel in their greed and their envy, their words are like hidden knives thirsting for blood.

Go and stand amidst their scowling hearts, my child, and let your gentle eyes fall upon them like the forgiving peace of the evening over the strife of the day.

Let them see your face, my child, and thus know the meaning of all things, let them love you and love each other.

Come and take your seat in the bosom of the limitless, my child.

At sunrise open and raise your heart like a blossoming flower, and at sunset bend your head and in silence complete the worship of the day. [6]

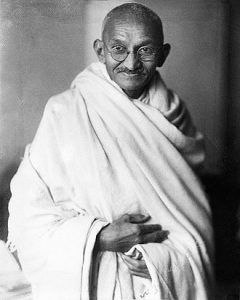

Studio photograph of Gandhi, 1931, Wikimedia Commons

And we find it in Mahatma Gandhi, the man who embodied the spirit, religious beliefs, cultures, and the humanistic aspirations of political struggle in his leadership of the struggle against the English during the war – or perhaps “peace” – of independence. We find it in his fight to unite India and win freedom. His ambition was to ensure that the river of freedom would continue to pour its pure waters into a sea of peace. He said, after all, that, “My interest in India’s freedom will cease if she adopts violent means. For their fruit will be not freedom, but slavery.” [7]

These men and many others like them form the landscape of cultural and political struggle in India, and represent the spirit of millions who live in a subcontinent rich with customs, traditions, myths, legends, music, dance, and sorcery. As well as languages and poetry, it is a land abundant in natural resources, with diverse industries and technological progress that has entered the space age.

Do we know or can we know enough about India, with its population of almost one billion, to do justice to its riches, vastness, and ancient civilisational and cultural history? We know something of Tagore, Gandhi, Neru, and a few other names that have made it through the wall of silence erected between our language and the languages of India, and even between our language and English in India. But do we think this knowledge entitles us to talk of the culture, literature, and civilisation of India? Likewise, what do Indians know of our culture, literature, and major writers? We know very little about their culture, literature, and major writers. Do they know even less?

Is this situation acceptable given the ancient history of connections and relations between India and Arab countries? Can this state of affairs continue despite the relatively short distance between us, and despite the bridges that still connect us in some way?

These are questions that cast a shadow on our intellectual consciousness, our culture, our literature, and our relationships with each other. They are questions that confront us when we look towards a better future for our culture and literature, our connections with the rest of the world world, and our political struggles alongside other nations.

In presenting this issue of Foreign Literatures about contemporary Indian literature today, we are all too aware of how much we are lacking, and the hard work we need to do to at the very least learn something about others in the East – our East. We consider this issue, therefore, to be merely a call to arms, a call to work towards building a deeper, firmer, and more comprehensive reciprocal awareness between Arab and Indian cultures. The issue also gestures towards a vital issue in relations between our nation and the peoples of India, for which both sides bear the responsibility of tackling: in particular intellectuals, writers, and authors. It is the efforts of such figures that can build constructive and creative bridges between different peoples. It is through their intellectual and creative contributions, and their deep-rooted connection to environment, culture, time in all its eternity, and humanity everywhere simultaneously, that human civilisation is built and we find our place in a springtime of peace, freedom, and ease.

Our hopes must be set on constructive and dedicated labour that spreads the light of knowledge and fruits of endeavour in the hearts and paths of humanity all over the earth. This way, one can dare to hope for more and attain a life of greater prosperity. This life is the “indestructible” life of the Upanishads, even if “these fleeting frames which it informs with spirit deathless, endless, infinite” perish [8].

In the Noble Qurʾan, it says, “They ask, ‘What is there but our life in this world? We die and we live, and only time destroys us.’ But they have no knowledge of this; they only conjecture” (Q 45:24). And, “They ask you about the Spirit. Say: ‘The Spirit is commanded by my Lord: of knowledge you have only been given a little’” (Q 17:85).

The poet, playwright, and critic Ali Ukla Ursan held a number of positions in the Syrian Ministry of Culture before becoming President of Arab Writers Union, Damascus 1977-2005. His tight control over the union over such a long period of time was criticised, especially following his expulsion of the well-known Syrian poet Adonis from the union in the 1990s. He was previously a member of the central committee of the Baath Party.

While his editorial draws mainly on Will Durant’s Story of Civilisation, the special issue itself contains a wide range of stories, translated via English, Russian, and even Albanian.

‘Foreign Literatures’. Journal published 4 times a year between 1974 and 2005 by Arab Writers Union, Damascus.

| al-Falsafah al-Hindīyah wa-ittijāhāt al-thaqāfah fī al-Hind

‘Indian Philosophy and Cultural Trends in India’ |

Nadrah al-Yāzijī |

| al-Shiʿr wa’l-shiʿrīyāt fī al-Hind al-qadīmah

‘Poetry and Poetics in Ancient India’ [Translation of material in Princeton Encyclopaedia of Poetry and Poetics (Enlarged Edition), 1974] |

Maḥmūd Munqidh al-Hāshimī |

| Mā al-Fann?

‘What is Art?’ |

Rabindranath Tagore

Trans. Muḥammad Jadīd |

| Mulāḥaẓāt fī al-shiʿr al-Hindī al-shābb

‘Observations about “Young/Youthful” Hindī/Indian poetry’ |

Alexander Senkevich

Trans. ʿĀdil al-ʿĀmil |

| Min al-ʿalāqāt al-adabīyah bayn al-ʿArab wa’l-Hunūd: qaṣaṣ makr al-nisāʾ al-Hindī wa-atharuhu fī al-Waṭan al-ʿArabī

‘Literary Relations between Arabs and Indians: Indian Wiles of Woman Tales and their influence in the [countries of the] Arab Nation’ |

Muḥammad Ḥamawīyah |

| Alṭāf Ḥusayn Hālī wa-fikrat Ilyūt ʿan al-turāth

‘Altaf Hussain Hali and Eliot’s conception of [Literary] Heritage’ |

M. Wasīm

Trans. Massarah al-Amīr |

| al-Khawlī

‘”Cooli” by Mulk Raj Anand: Study and Analysis by ʿĀdil ʿAbd Allāh’ |

ʿĀdil ʿAbd Allāh |

| al-Qiṣṣah al-Hindīyah

‘The Indian [Short] Story’ |

Sālim Jabārah |

| al-Yarāʿāt

‘Fireflies’ |

Rabindranath Tagore

Trans. Badīʿ Ḥaqqī |

| Shuʿarāʾ muʿāṣirūn fī al-Hind

‘Contemporary Poets in India’ [Selections from different poets] |

Trans. Saʿd Ṣāʾib |

| Nafaḥāt min al-shiʿr al-Hindī

‘Selections of Hindi/Indian poetry’ [Translated from Albanian!] |

Trans. ʿAbd al-Laṭīf Arnāʾūṭ |

| Nīlā…muʿallimat al-madrasah

‘Nīla the schoolmistress’ [A footnote introduces Godabarish Mohapatra (1889-1985) as a poet, short story writer, novelist, and newspaper editor who writes in Odia/Oriya and who has won the [Odisha] Sahitya Akademi award] [Translated from English] |

Godabarish Mohapatra

Trans. Aḥmad Ziyād Maḥbak |

| al-Awrāq al-mutasāqiṭah…wa-ashʿār ukhrá

‘Fallen leaves and other poems’ [Has an extended biographical note about Bengali poet Prodosh Dasgupta (also a sculptor)] [Translated from English] |

Prodosh Dasgupta

Trans. Manāl al-Jubūrī |

| Ughniyāt Jadīdah

‘New Melodies’ by Narayan Gangopadhyay [Has a short biography of author and comments that the story tells of the unrest in East Bengal when the population called for Bengali to be the official language of that part of Pakistan. Story contains numerous footnotes] [Translated from Russian] |

Narayan Gangopadhyay

Trans. Shawkat Yūsuf |

| Ḥārisat al-aḥibbah

‘The Guard of Lovers’ Short story by Punjabi writer Gurbaksh Singh with a biography |

Gurbaksh Singh

Trans. Ibrāhīm Yaḥyá al-Shahābī |

| al-Maskh

‘Metamorphosis’ Short story by Punjabi writer Raghubir Dhand with a short biography |

Raghubir Dhand

Trans. Ibrāhīm Yaḥyá al-Shahābī |

| Amrītsār aṣbaḥat khalfanā

‘Amritsar is behind us’ [Seems to be a mistranslation of Amritsar ā gayā hai]Short story by Hindi writer Bhisham Sahni with short biography [Translated from Russian] |

Bhisham Sahni

Trans. Akram Sulaymān |

| al-Khiyānah

‘Betrayal’: Short Story by Sujatha Bala Subramanyiam Source is given as Portrait of India: Selection of Short Stories ed. Shiv K. Gupta, New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1983) |

ujatha Bala Subramanyiam

Trans. Saʿdī Aḥmad Dāwūd |

| Min asāṭīr al-Hind: al-Ramāyānā

‘From the myths of India: the Ramayana’ (A short study/discussion and summary of this epic and the Mahabharata) |

Walīd Mushawwaḥ |

These images are available on an open image licence. Read them in the original journal here.

| al-Falsafah al-Hindīyah wa-ittijāhāt al-thaqāfah fī al-Hind

‘Indian Philosophy and Cultural Trends in India’ |

Nadrah al-Yāzijī |

| al-Shiʿr wa’l-shiʿrīyāt fī al-Hind al-qadīmah

‘Poetry and Poetics in Ancient India’ [Translation of material in Princeton Encyclopaedia of Poetry and Poetics (Enlarged Edition), 1974] |

Maḥmūd Munqidh al-Hāshimī |

| Mā al-Fann?

‘What is Art?’ |

Rabindranath Tagore

Trans. Muḥammad Jadīd |

| Mulāḥaẓāt fī al-shiʿr al-Hindī al-shābb

‘Observations about “Young/Youthful” Hindī/Indian poetry’ |

Alexander Senkevich

Trans. ʿĀdil al-ʿĀmil |

| Min al-ʿalāqāt al-adabīyah bayn al-ʿArab wa’l-Hunūd: qaṣaṣ makr al-nisāʾ al-Hindī wa-atharuhu fī al-Waṭan al-ʿArabī

‘Literary Relations between Arabs and Indians: Indian Wiles of Woman Tales and their influence in the [countries of the] Arab Nation’ |

Muḥammad Ḥamawīyah |

| Alṭāf Ḥusayn Hālī wa-fikrat Ilyūt ʿan al-turāth

‘Altaf Hussain Hali and Eliot’s conception of [Literary] Heritage’ |

M. Wasīm

Trans. Massarah al-Amīr |

| al-Khawlī

‘”Cooli” by Mulk Raj Anand: Study and Analysis by ʿĀdil ʿAbd Allāh’ |

ʿĀdil ʿAbd Allāh |

| al-Qiṣṣah al-Hindīyah

‘The Indian [Short] Story’ |

Sālim Jabārah |

| al-Yarāʿāt

‘Fireflies’ |

Rabindranath Tagore

Trans. Badīʿ Ḥaqqī |

| Shuʿarāʾ muʿāṣirūn fī al-Hind

‘Contemporary Poets in India’ [Selections from different poets] |

Trans. Saʿd Ṣāʾib |

| Nafaḥāt min al-shiʿr al-Hindī

‘Selections of Hindi/Indian poetry’ [Translated from Albanian!] |

Trans. ʿAbd al-Laṭīf Arnāʾūṭ |

| Nīlā…muʿallimat al-madrasah

‘Nīla the schoolmistress’ [A footnote introduces Godabarish Mohapatra (1889-1985) as a poet, short story writer, novelist, and newspaper editor who writes in Odia/Oriya and who has won the [Odisha] Sahitya Akademi award] [Translated from English] |

Godabarish Mohapatra

Trans. Aḥmad Ziyād Maḥbak |

| al-Awrāq al-mutasāqiṭah…wa-ashʿār ukhrá

‘Fallen leaves and other poems’ [Has an extended biographical note about Bengali poet Prodosh Dasgupta (also a sculptor)] [Translated from English] |

Prodosh Dasgupta

Trans. Manāl al-Jubūrī |

| Ughniyāt Jadīdah

‘New Melodies’ by Narayan Gangopadhyay [Has a short biography of author and comments that the story tells of the unrest in East Bengal when the population called for Bengali to be the official language of that part of Pakistan. Story contains numerous footnotes] [Translated from Russian] |

Narayan Gangopadhyay

Trans. Shawkat Yūsuf |

| Ḥārisat al-aḥibbah

‘The Guard of Lovers’ Short story by Punjabi writer Gurbaksh Singh with a biography |

Gurbaksh Singh

Trans. Ibrāhīm Yaḥyá al-Shahābī |

| al-Maskh

‘Metamorphosis’ Short story by Punjabi writer Raghubir Dhand with a short biography |

Raghubir Dhand

Trans. Ibrāhīm Yaḥyá al-Shahābī |

| Amrītsār aṣbaḥat khalfanā

‘Amritsar is behind us’ [Seems to be a mistranslation of Amritsar ā gayā hai]Short story by Hindi writer Bhisham Sahni with short biography [Translated from Russian] |

Bhisham Sahni

Trans. Akram Sulaymān |

| al-Khiyānah

‘Betrayal’: Short Story by Sujatha Bala Subramanyiam Source is given as Portrait of India: Selection of Short Stories ed. Shiv K. Gupta, New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1983) |

ujatha Bala Subramanyiam

Trans. Saʿdī Aḥmad Dāwūd |

| Min asāṭīr al-Hind: al-Ramāyānā

‘From the myths of India: the Ramayana’ (A short study/discussion and summary of this epic and the Mahabharata) |

Walīd Mushawwaḥ |

Leave A Comment