Hailing from Oakland, California, Ronah Baha is an MA candidate in Gender Studies at SOAS, University of London. Her current research examines the relationship between Afghan-American diasporic nostalgia and visual representations of Afghan women from the 1960s and 1970s. Her other interests include migration, literature, food, and the Persianate world.

What’s in a Name? On Afghanistan’s Fraught Persian Language Politics

In November 2017, chaos erupted when the Afghan branch of BBC Persian changed the name of its Facebook page to from ‘BBC Afghanistan’ to ‘BBC Dari.’ The change touched a nerve among Afghan Persian speakers, hundreds of whom took to Facebook and journalistic outlets to declare that their language is called Farsi and not Dari, the name designated by the Afghan government. In the following weeks, hundreds of posts marked with the hashtag #Unlike_BBC_Dari inundated Persian-language social media. Iranian, Afghan, and diasporic news stations – including some of the BBC’s own programming – broadcasted debates on the subject. And one petition amassed over 3,000 signatures demanding that the name be changed back. A recurring theme in the signatory comments reveals the focal point of the outrage: “My language is Farsi (Persian),” one comment reads. “BBC has no right to make a name for my language.”

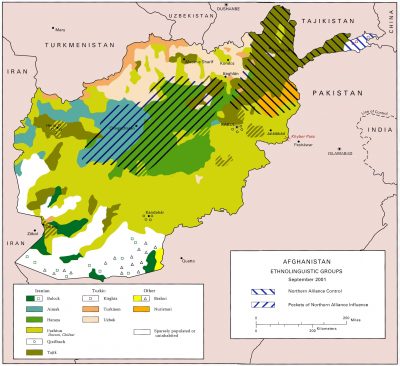

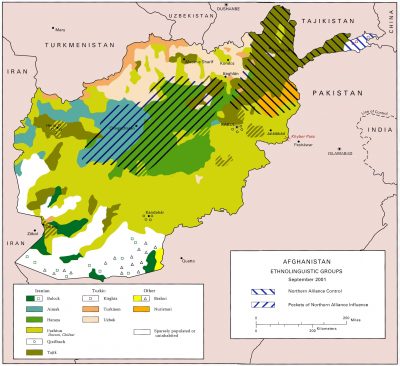

With the seemingly unwitting change of a Facebook name, the BBC mired itself in one of the Persian-speaking world’s most contentious conflicts of linguistic identity. In response to the outcry, the head of the Afghan subdivision of the BBC World Service, Mina Baktash, attempted to explain the decision: “BBC believes that in order to better reach our audiences, we must speak in their accent and idiom. Dari is named as one of the official languages of Afghanistan in that country’s constitution.” Baktash is not wrong on this latter count: the current constitution designates Dari (not Farsi) and Pashto as the two official languages of Afghanistan. (Pashto is spoken by Pashtuns, the country’s largest ethnolinguistic group, while Persian is spoken by a majority contingent of ethnic minorities including Tajiks, Aimaqs, and Hazaras. Many urban Pashtuns speak both languages; some even speak Persian exclusively.)

However, Dari has a relatively short history as a constitutionally recognized language. It first appeared alongside Pashto in the Afghan constitution of 1964, under the constitutional monarchy of Mohammad Zahir Shah. Radio Free Europe reported that according to the late Afghan historian Mir Mohammad Sediq Farhang, prior constitutions referenced Farsi, but not Dari. Farhang surmised that Dari came into use as a compromise between Pashtun political elites and Persian speakers. Some Pashtuns sought to designate Pashto as the sole official language but conceded to incorporate Persian under the name ‘Dari’ to distinguish it from Farsi, which was deemed to belong to Iran. This decision ostensibly served two political purposes: first, it bolstered Afghan nationalism by demarcating a separation between Afghan and Iranian Persian and asserting an independent linguistic identity for Afghanistan. (A similar dynamic exists in Tajikistan, where the national dialect, ‘Tajiki’, is often regarded as a separate language altogether.) Second, some have argued that it re-inscribes Pashtun dominance by dissociating Afghan Persian speakers from the Persian-speaking world around them.

Given these political entanglements, Afghan Persian speakers were unimpressed when Baktash attempted to disavow the broader implications of BBC’s name change, writing, “We changed the name of the page ‘BBC Afghanistan’ because this page usually reflects the radio programming of BBC Dari radio… There is no political or cultural motivation behind this decision” (emphasis added). But to Afghanistan’s Persian speakers, the majority of whom refer to their language as Farsi, the name Dari is inherently political. Baktash and the BBC have failed to account for the fraught nature of Persian language politics, wherein linguistic taxonomy is intertwined with ethno-nationalisms, claims to literary canon, and regional hegemony.

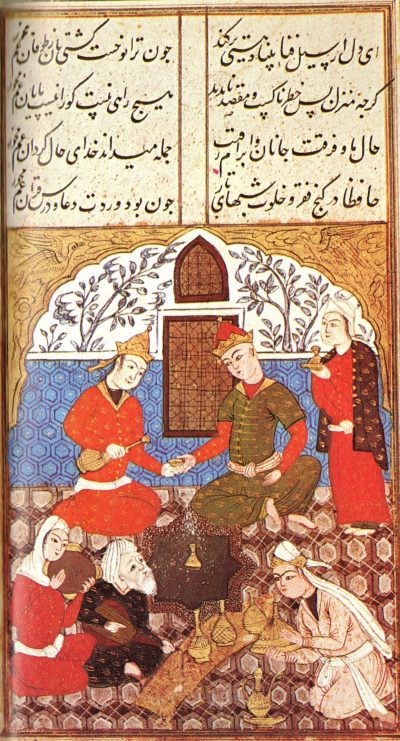

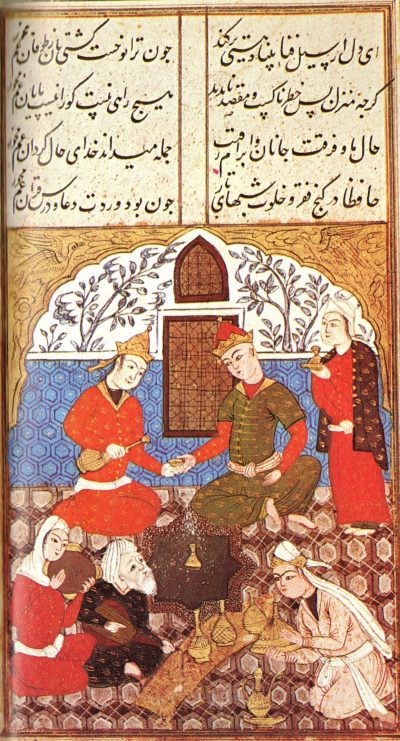

Those petitioning the BBC are protesting the separation of their language from the Persian spoken in Iran, Tajikistan, and elsewhere. Moreover, they do not want to be divorced from their Persian (Farsi) literary and civilizational heritage. Many signatories insist upon unity in ‘Pan-Iranism’, declaring, “The language of Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan is Persian!” and “The civilization and heritage of our forefathers, scholars, and poets are known as Farsi.” A near-consensus among scholars of the region confirms that Farsi and Dari are the same language. In an episode of BBC Persian’s program Pargar, Afghan linguist Najibullah Fariwar points to classical Persian poetry, asserting that the words ‘Farsi’ and ‘Dari’ are used interchangeably. According to Fariwar, Dari gradually fell out of use – except with reference to literature – while Farsi continued to be used both formally and colloquially. Some refer to Dari as a dialectof Persian (Farsi), but historian James Pickett problematizes this claim, arguing that the categorization of dialects along national lines exaggerates distinctions between formal registers of Persian in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Iran – which are in fact minimal – while obscuring the extensive linguistic diversity within each country.

All of these arguments point toward Persian linguistic unity and the use of Farsi to refer to the language. However, it is also important to be cautious about the uncritical propagation of Pan-Iranism. We need to recognize the mutual intelligibility and shared history amongst dialects of Persian. But we must also recognize the diversity within the language – as well as the power dynamics that determine what it is called and how it is spoken. Farsi is the common name for Persian at least partly because of Iranian cultural and linguistic hegemony in the region, and Pan-Iranist ideology, first promoted by the Pahlavi dynasty in Iran, has often served as a guise for the reproduction of hegemony. This dynamic is manifest when Iranian critics deride Afghan literary output, claiming that it is derivative of their own national canon. It has appeared in the insistence that words common to Iranian usage be incorporated into Afghan and Tajik vocabularies. And it was laid bare when the Iranian and Turkish governments submitted a request to list Rumi as their joint heritage on UNESCO’s “Memory of the World” register in 2016, ignoring Afghanistan’s shared claim to the literary giant. Afghanistan’s Persian speakers are right to push back against the BBC. But they must also determine how to assert their linguistic identities and claim to Persian literary heritage while simultaneously resisting uncritical assimilation to contemporary Iranian linguistic culture. The richly diverse heritage of the Persian-speaking world is at stake.

Hailing from Oakland, California, Ronah Baha is an MA candidate in Gender Studies at SOAS, University of London. Her current research examines the relationship between Afghan-American diasporic nostalgia and visual representations of Afghan women from the 1960s and 1970s. Her other interests include migration, literature, food, and the Persianate world.

What's in a Name? On Afghanistan's Fraught Persian Language Politics

In November 2017, chaos erupted when the Afghan branch of BBC Persian changed the name of its Facebook page to from 'BBC Afghanistan' to 'BBC Dari.' The change touched a nerve among Afghan Persian speakers, hundreds of whom took to Facebook and journalistic outlets to declare that their language is called Farsi and not Dari, the name designated by the Afghan government. In the following weeks, hundreds of posts marked with the hashtag #Unlike_BBC_Dari inundated Persian-language social media. Iranian, Afghan, and diasporic news stations – including some of the BBC's own programming – broadcasted debates on the subject. And one petition amassed over 3,000 signatures demanding that the name be changed back. A recurring theme in the signatory comments reveals the focal point of the outrage: "My language is Farsi (Persian)," one comment reads. "BBC has no right to make a name for my language."

With the seemingly unwitting change of a Facebook name, the BBC mired itself in one of the Persian-speaking world's most contentious conflicts of linguistic identity. In response to the outcry, the head of the Afghan subdivision of the BBC World Service, Mina Baktash, attempted to explain the decision: "BBC believes that in order to better reach our audiences, we must speak in their accent and idiom. Dari is named as one of the official languages of Afghanistan in that country's constitution." Baktash is not wrong on this latter count: the current constitution designates Dari (not Farsi) and Pashto as the two official languages of Afghanistan. (Pashto is spoken by Pashtuns, the country's largest ethnolinguistic group, while Persian is spoken by a majority contingent of ethnic minorities including Tajiks, Aimaqs, and Hazaras. Many urban Pashtuns speak both languages; some even speak Persian exclusively.)

However, Dari has a relatively short history as a constitutionally recognized language. It first appeared alongside Pashto in the Afghan constitution of 1964, under the constitutional monarchy of Mohammad Zahir Shah. Radio Free Europe reported that according to the late Afghan historian Mir Mohammad Sediq Farhang, prior constitutions referenced Farsi, but not Dari. Farhang surmised that Dari came into use as a compromise between Pashtun political elites and Persian speakers. Some Pashtuns sought to designate Pashto as the sole official language but conceded to incorporate Persian under the name 'Dari' to distinguish it from Farsi, which was deemed to belong to Iran. This decision ostensibly served two political purposes: first, it bolstered Afghan nationalism by demarcating a separation between Afghan and Iranian Persian and asserting an independent linguistic identity for Afghanistan. (A similar dynamic exists in Tajikistan, where the national dialect, 'Tajiki', is often regarded as a separate language altogether.) Second, some have argued that it re-inscribes Pashtun dominance by dissociating Afghan Persian speakers from the Persian-speaking world around them.

Given these political entanglements, Afghan Persian speakers were unimpressed when Baktash attempted to disavow the broader implications of BBC's name change, writing, "We changed the name of the page 'BBC Afghanistan' because this page usually reflects the radio programming of BBC Dari radio… There is no political or cultural motivation behind this decision" (emphasis added). But to Afghanistan's Persian speakers, the majority of whom refer to their language as Farsi, the name Dari is inherently political. Baktash and the BBC have failed to account for the fraught nature of Persian language politics, wherein linguistic taxonomy is intertwined with ethno-nationalisms, claims to literary canon, and regional hegemony.

Those petitioning the BBC are protesting the separation of their language from the Persian spoken in Iran, Tajikistan, and elsewhere. Moreover, they do not want to be divorced from their Persian (Farsi) literary and civilizational heritage. Many signatories insist upon unity in 'Pan-Iranism', declaring, "The language of Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan is Persian!" and "The civilization and heritage of our forefathers, scholars, and poets are known as Farsi." A near-consensus among scholars of the region confirms that Farsi and Dari are the same language. In an episode of BBC Persian's program Pargar, Afghan linguist Najibullah Fariwar points to classical Persian poetry, asserting that the words 'Farsi' and 'Dari' are used interchangeably. According to Fariwar, Dari gradually fell out of use – except with reference to literature – while Farsi continued to be used both formally and colloquially. Some refer to Dari as a dialectof Persian (Farsi), but historian James Pickett problematizes this claim, arguing that the categorization of dialects along national lines exaggerates distinctions between formal registers of Persian in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Iran – which are in fact minimal – while obscuring the extensive linguistic diversity within each country.

All of these arguments point toward Persian linguistic unity and the use of Farsi to refer to the language. However, it is also important to be cautious about the uncritical propagation of Pan-Iranism. We need to recognize the mutual intelligibility and shared history amongst dialects of Persian. But we must also recognize the diversity within the language – as well as the power dynamics that determine what it is called and how it is spoken. Farsi is the common name for Persian at least partly because of Iranian cultural and linguistic hegemony in the region, and Pan-Iranist ideology, first promoted by the Pahlavi dynasty in Iran, has often served as a guise for the reproduction of hegemony. This dynamic is manifest when Iranian critics deride Afghan literary output, claiming that it is derivative of their own national canon. It has appeared in the insistence that words common to Iranian usage be incorporated into Afghan and Tajik vocabularies. And it was laid bare when the Iranian and Turkish governments submitted a request to list Rumi as their joint heritage on UNESCO's "Memory of the World" register in 2016, ignoring Afghanistan's shared claim to the literary giant. Afghanistan's Persian speakers are right to push back against the BBC. But they must also determine how to assert their linguistic identities and claim to Persian literary heritage while simultaneously resisting uncritical assimilation to contemporary Iranian linguistic culture. The richly diverse heritage of the Persian-speaking world is at stake.

Thank you for writing this, it was a refreshingly balanced article that examined both perspectives!

Thank you for this piece. I agree with the author to a large extent except for the final remarks that assumes assimilation to contemporary Iranian linguistic culture. While this is partly true and results from more abundant cultural production in Iran, we should also bear in mind that literature from Tajikistan and Afghanistan has also influenced and enriched the linguistic and literary output in Iran (though in a less significant manner).