This essay was translated into English by Maryam Iraj as part of MULOSIGE’s Translations project. This project includes translations of essays of world literature from Urdu to English, as well as an our archive of translated Progressive and Modernist Urdu Poetry.

Songs of the Goliards (or travelling students)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

“Jahan-gard tulba key gīt”

from Mashriq o Maghreb ke naghme (Songs of East and West)

by Meeraji/ Mohammad Sanaullah Dar (1912-1949)

.

Translated into English by Maryam Iraj

To find the original essay in Urdu, please turn to pages 19 – 43 here.

Before we can listen to and appreciate songs of the vagabond students, or Goliards, from 12th century AD, it is fundamentally important to understand several aspects of European life. These vagabond students belonged to an exclusive group and their songs cannot be fully understood unless we develop wide-ranging insight into their lifestyles.

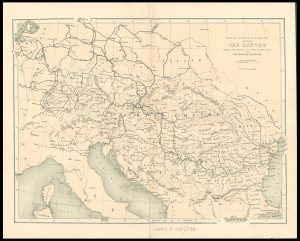

Map of Central Europe. Source: Wikimedia Commons

When we attempt to encompass the intellectual and moral situation of Central Europe, we often fall prey to biased and predetermined notions about their lives. We tend to believe that in that particular period, every nation in Europe, was in a deep slumber, that Greek and Roman intellectual enterprises were gradually fading away and that an invaluable treasure was left to rot in libraries and be eaten by moths. [We believe that] people of every nationality were becoming extremists in fearful wait of the Day of Judgment and in their inclination towards religious virtues, they considered all the pleasures of life essentially a fatal sin. And that, when given the opportunity, they submitted to their carnal desires with a primitive and wild curiosity. Exaggerated thoughts of the world-hereafter did not leave them with enough wisdom to control those aspects of life which could make their lives valuable and wholesome in this world.

The thoughts of sages and philosophers from these times reached an apex of ignorance. They exhausted themselves in developing, arguing and critically analyzing question and issues which had neither a connection nor a remote relevance with reality. Authentic experiences augmented by observations and arguments and the tendency to independent study had been diminished by the religious frenzy. The entire society was buried underneath this immense pressure of ignorance. Religious clerics poisoned the thoughts of their followers with vexatious and tormenting accounts of the hell and divine punishment. Making pilgrimages to holy sites and wearing amulets was the one and only resort to salvation. Since the natural intellectual growth of the human mind was generally barricaded, people turned to magic and diabolical fancies to strengthen their ties with evil powers. They were completely lost in this absurd imagination of the world around them. The actual status of the woman was lost. At one extreme, she was treated as nothing more than an object of pleasure. And at another, she was placed on the highest and ultimate pedestal of divinity. Common sense, the power of logical and critical decision-making, and a substantial grip on reality was missing from the lives of these people. They lost contact with the reasonable goals of day-to-day life due to their misconceptions of the world around them. Instead of being inclined towards the exploration of the facts of a routine life, they were more disposed to chasing surreal and eroding shadows of ignorance in the hope of fortifying that future over which they had no control over. But the life they were actually living was never a point of concern or frame of reference for these people. The only major accomplishment of that particular era of Western Europe was—the crusades, and it was a blunder that led to nothing but a bloodbath.

This is the situation which comes into focus when studying about Central Europe. But that was certainly only one side of the story. Since the nucleus of such an exaggerated analysis is the result of the knowledge which monks and religious clerics laid their foundations on, there is no denying that the intellectual activity of that particular era of Central Europe was unnaturally blurred. One can’t find such precedence anywhere else except in the fall of Rome or during the middle of the thirteenth-century AD. Notwithstanding all the reasons stated above, there are still untapped aspects of that era which can prompt us to view those times more favorably. In the early Middle Ages, ancient civilization and culture were definitely finished but the last half of that era gave birth to a peculiar group of unreasonable and irrational people with whom the dark tradition of rusty ideas and conservative thoughts lasted. The intellectual capacity and conscience of people became accustomed to the imaginative world and the fears which religious clerics propagated. All this practice was subservient to the manipulation and wrong use of the natural capabilities of man.

Therefore, when we encounter the Latin songs of vagabond-students (Goliards) with our preconceived impressions of that era we are left flabbergasted. In their songs, unlike the usual thought-patterns of those times, one finds fresh, novel, and more natural choices of poets. This unusual frame of comparison compels us to establish a more balanced opinion about the Middle Ages. Both men and women had the same natural urges and desires, which were as deeply embedded and forcefully exhibited in the times of the Greeks and the Romans or after the Renaissance. But one thing needs to be appreciated and understood that such natural ventures lacked particular maturity and discipline. The wandering minstrels and nomads who gave birth to this poetry belonged to a lower status among religious students. Their poetry reflected a more common view of life. Although these poets had their hands on the pulse of a common man, we nonetheless get to also see a religious and intellectual discourse when we read their poetry in depth.

Therefore, when we encounter the Latin songs of vagabond-students (Goliards) with our preconceived impressions of that era we are left flabbergasted. In their songs, unlike the usual thought-patterns of those times, one finds fresh, novel, and more natural choices of poets. This unusual frame of comparison compels us to establish a more balanced opinion about the Middle Ages. Both men and women had the same natural urges and desires, which were as deeply embedded and forcefully exhibited in the times of the Greeks and the Romans or after the Renaissance. But one thing needs to be appreciated and understood that such natural ventures lacked particular maturity and discipline. The wandering minstrels and nomads who gave birth to this poetry belonged to a lower status among religious students. Their poetry reflected a more common view of life. Although these poets had their hands on the pulse of a common man, we nonetheless get to also see a religious and intellectual discourse when we read their poetry in depth.

The European Middle Ages yielded a revival which was ahead of its times, The center of this revival was in France where it blossomed through the middle and later half of the twelfth-century AD. Moreover, two centuries prior to Luther, England engendered similar movements that spread across Eastern Europe. Songs of the students produced in the 12th- century were reflective of those movements which people effectuated after being liberated from the so-called spiritual trappings of that era. Their poetry reflected those unbridled emotions, veering slightly towards vulgarity, that were widespread in society at the time. It also acquaints us with a particular group that was unique in its thoughts and echoes two trajectories: first, a life which was centered around the worldly physical pleasures—a core attribution of the Renaissance—and second, a general resistance (and revolutionary sentiment) which was engendered in subversive reaction to the Roman Catholic Church.

Photo by Boudewijn Huysmans on Unsplash

This analysis of poetry is based on two counts. First, the manuscript that was found in the monastery located in the upper part of Bavaria. Second, that manuscript was written prior to the year 1264 AD and was published in the year 1842 AD. Many poems are common in these two manuscripts. But in the first manuscript, poems which were written prior to the renaissance of art and science are common. However, in the second manuscript, their poetry obtains a serious and a satirical tone. Apart from these two manuscripts, writings of many German and French scholars also shed light on the poetry of the vagabond students.

Before we discuss the songs, we also need to have a look at the personal lives and creative analysis of those poets.

Photo by Lea Khreiss on Unsplash

Romans, even at the peak of their intellectual enterprise, created poetry in a very easy and natural poetic meter. But, then, they adopted a complex and rigid poetic meter in order to emulate Greek intellectuals. Irrespective of the reality embedded at the core, there is no doubt that easier and more natural poetic meter were incorporated in the Latin poetry in place of the fixed and difficult meter with the decline of old civilization and culture. Liturgical music paved the way for new poetic expressions. Rhyming gained currency in poetry and many other inventive methods were brought into practice. Hence, this new wave rendered poetry of that era varying shades of creativity at multiple degrees. Songs exuded novelty, blooming cheerfulness, and an unusual narrative disclosure. Despite being called the ‘Dark Ages’, the poetry of that era still had reminiscences of idolatry; characteristic of freedom and fearless creative expressions, or it could also be called the remote calling of modern day’s expressions of untainted truth. Even some examples are present in the poetry of the 7th and 10th-centuries to prove this point that despite being in constant fear of the Day of Judgment and Doom’s Day, people never entirely effaced the singing, the poetry, drinking, and most importantly—women. Against all prevalent social norms, they had the capacity to revel in the worldly pleasures with a critical mind to endorse the essence of it.

There is no need to analyze in detail the Latin poetry of the early period of the Middle Ages. For the preceding examples, a mere reference can serve the purpose. Because the 12th-century renaissance in arts and science and the former creative decline had only this particular yet subtle evolving concatenation. The same link seams into the intellectual and creative peaks achieved in the 14th and 15th-century’s Italian Renaissance. There are three characteristics of this peculiar form of poetry in the Middle Ages. The first quality is that of music which stole the limelight in comparison of the sheer dry-versification. Hence, the ancient poetic meters were rendered new meanings with melody and kindred rhymes. Second, the religious poetry of common man forsook the highly scholastic and intellectual poetry of monasteries. And the third feature of the poetry of the Middle Ages in the darkest intellectual period was the amalgamation of liberalism and skepticism in its thematic structures. Redolence of the old deities and idols! Resounding whispers of those exiled gods who still aroused man to savor of worldly pleasures, endured across the stretches of Europe without being extinct in principal.

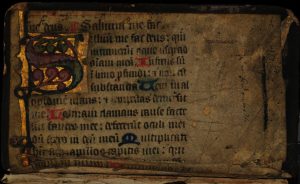

12th century illustration. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Another significant point to understand the dynamic behind the unique spells of poetry of the Dark Ages was that people were under the impression that their language did not pick the innuendos and subtleties with which they expressed themselves in Latin.

These songs of the vagabonds (Goliards) are not expressions of a scholastic quality, they were appreciated and ratified by the masses. Nonetheless, the creators of these songs were highly sophisticated, civilized, and excelled in one art form or the other— specifically, they could be easily considered erudite scholars of Latin language without any exaggeration. But who were these vagabonds? Fleeting references could be found in the history of European literature but nothing in detail and with complete references was available to substantiate this point.

As evident from their names, they were wandering vagabonds who glob-trotted in search of seeking knowledge. Being away from their countries, without bearing any responsibility, money, or worries, they spent a leisurely life while listening to music, drinking and attending to their favourite topic: woman. Instead of seeking knowledge in a lecture-room, they preferred to grace the bars. Many subjects were taught in different countries in the Middle Ages; therefore, it was inevitable for a student to travel from one country to another in search of knowledge. And following the crusades, there was restlessness among public which led to the pursuit of traveling among all classes of society. For visiting the holy places, trade to give a boom to the industry, and in terms of seeking knowledge; the depth of interest in wandering from place to place amplified.

A 12th-century monk wrote in this regard, “for a scholar, it is mandatory to travel the world and reach out to every city until he reaches to the point of insanity as his knowledge brims over.”

Photo by Mattia Faloretti on Unsplash

As the Buddhists sailed through the world in search of knowledge, the same way these wandering students and vagabonds reached out to each and every corner of many countries. But among those, there was a group who trotted the globe in critically analyzing the knowledge they gained and stood apart in the way they approached knowledge. Because neither they belonged to a certain religious group nor they took oath or were bound by a certain tradition. They reviled to be in contact with civilians and shunned to keep in with them. Though they had no particular animosity toward the knighthood but considered themselves superior to them. However, by nature or to respond to the need of the hour, they were permissive and radical in their spirits. In the pretext of the prevalent milieu of the Middle Ages, these seekers of knowledge were also considered to be part of a certain group. Even the poetry they wrote clearly expressed the brotherhood and affinities among them. Such instinctive desires and social needs prompted them to be organized in a group. Based on this fact, they were in need of appointing a spiritual head who was as free and licentious in his thoughts as they were. The status of this spiritual leader was equivalent to that of a wine-seller in a wine-house. This group was called the Goliards and the head of the Goliards’ cherished the status of a family-head who took care of his mystic disciples.

Now the question arises whether they were named after some person called Goliard or were naturally called Goliards after being formed in a group. This question regarding the background of the given title “Goliard” is difficult to answer. However, in literal terms, it is a derivative of the word “Gula” which means gluttony or someone fond of food and worldly pleasures. If we connect it with the galliard—it means lively or gay. Either of these meanings, Gula or Galliard, suggests a licentious, carefree and illusory attitude in which one doesn’t take life too seriously. Be that as it may, the word goliard was commonly used for vagabonds or young clergymen as evidenced by manuscripts from the Middle Ages. Therefore, we need to analyze the works of Goliards as the creative consummation of a particular group. Irrespective of the absence or rarity of details available about the lives and background of the poets, these songs had been written by various poets ascertaining their unique intellectual and creative bearings after critically analyzing their works. And it can be fairly and easily established following a thorough study.

Religious manuscripts also reveal the fact that these young clergymen or Goliards were nothing more than vagabonds or jokers who provided entertainment to those who were superior to them in religious status. Jokers/jesters and these vagabonds stood on equal footing. Barring few exceptions, either of these groups (jokers or vagabonds) had no permanent place to live.

In all creative works of the vagabonds, the personality of the poet gradually fades to be completely vanished towards the end of the songs.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Instead of the unique name of the poet, only the unique narrative remains intact in the memory of the reader while studying their unique verses. Songs of the vagabonds or Goliards when delivered by the respective poets represented the unique group-identities. A salient feature of famous literary works is that of its recognition and acceptability among masses because they are emblematic of collective feelings instead of individual outpourings of a poet. Such collective depictions of human emotions in literature enables the masses to endorse the creative ingenuity of the poet. However, the only hindrance or a minuscule fissure in appreciating the full potential of these poets is that of their social and temporal relevance globally. It is exactly in the same manner the way life of a peasant is depicted locally in the rustic songs to highlight the difference between the urban and rural lifestyles. Songs of the vagabonds also unveil the symbolic and partial characteristics of that particular life which Goliards lived. The lyrical feeling in their songs are true and authentic. While giving vent to poetic feeling, a deep connection to reality always remain intact. However, the depth and affinities which the individual and personal voice of the poet creates evanesces. Because while versifying, these poets delineated the voice of thousands of human beings. Just like the rural songs, the global appeal of these songs dissipated the individual qualities of a poet’s voice. Interest developed through unique individual realities in specific situations is atoned in the name of a mega-narrative. Such songs belong to every soul who is bereaved and in blues, in search of someone or to conquer somebody. These songs are not reflective of a single individual’s personal gains, love or to win over the world instead of leaving the world. Many songs transferred these grand human emotions from generation to generation. However, the difference is identical to that of Ghalib, Mir, or Daagh’s poetry. Despite portraying human emotions, their poetic ingenuity is veiled in the voice sustained to convey collective human emotions. Such songs instantly become the public property once they are penned down and published, and cruise across the countries through oral traditions. After reaching a particular point, the journey of such songs comes to an end, and new songs take its positions. If editorial scissors are sharpened on these classics, relevance to its original form is lost, however, a newer form of verse is brought into existence. Therefore, we must rescind the identity of poets or their individual voices as they lose their distinct significance in the presence of a larger literally narrative famous among and deeply endorsed by the masses. We shall also not bring into focus the nationalities of those poets as they are equally owned and cherished by England, France, Germany and Italy. In addition, Latin was the lingua franca across Europe during the Middle Ages, hence, it becomes increasingly difficult to determine the identity of the poet based on their nationalities. However, reference to J. A. Symonds is pertinent to the ongoing argument. According to him, these songs of the vagabonds were related to the South-West Germany and Bavaria. Especially, the intensity of songs that are connotative of love and the luster of spring project a German connection. Songs that are depictive of English politics could be attributed to England, and then there were songs attributed to a French poet. Then there were lines repeated at the closing of each stanza in French could also be attributed to France. In the same way, songs in which olives and juniper trees were referred could be attributed to Italy or at least affected by the Italian circumstances.

Two significant points could be attributed with relationship to the essence and nature of these songs: First, these were written in tradition of hymns or religious poetry regarding their poetic meter. But all these songs were satirical and descriptive in nature. Secondly, those which were not written in the metrical fashion of hymns were, in fact, according to the lyrical needs of the songs of the vagabonds; as they were primarily written to be sung. At times, the rhyme-scheme was stretched and composed in a highly complex manner. And, at times, rhyme was completely absent in some of their poetry. Hence, the form varied according to the nature of the theme of a particular song.

Photo by Claudio Carrozzo on Unsplash

Thematically, these songs are divided into two broad categories: in the first half, themes are highly centered around the nonconformist and free-spirited lifestyle of the vagabonds. Concepts of rural life, talks of spring, and memories of amorous love, tales of different females, stories of seduction and booze are central to the first category. In the second category, attention is paid to the solemn aspects of life. It reflects on the serious issues of life with the help of social satire, especially to lampoon the Roman palace, sketching the lives of religious leaders of those times who emulated the soul of Dark Ages through their practices and preaching. This category also reckoned the transience of life. Now, a general impression is that the poetry of the first category exudes subtleness and humour. However, this is the second category which projects these characteristics. The latter category is depictive of comparatively serious, bold, and sincere themes. Instead of paying the entire attention to the dry composition of the couplets, the latter focused on the social issues. Since the lives of the vagabonds and Goliards was different from the predominant social norms, they could easily reflect on the incongruities of the society around them in a more satirical and ironical manner.

Nature and natural sceneries have always played an instrumental role in the poetry of Goliards. Love and the aftermath of love is always nurtured in the lands and woods marked with the exquisiteness of spring. Flowers are blossoming in abundance; streams are harmoniously flowing, winds are rustling through the lime, juniper, and olive trees. Rose-gardens and nightingales. Gentle steps of gazelles, and the charming fairies in woods lost in the dance with the god of the jungle pacing around the green pastures in divine rhythm. And, then, there are also mortal females appearing in groups singing the songs of joy—these narratives are illustrating poets’ imagination and the intensity of their emotions. In addition, it also reflects the buoyant and fresh impressions full of life’s exuberance. It also echoes the nomadic life and the spells of entertainment of these vagabond poets who are in a constant state of moving from one place to another. Their lives go with a natural flow and is not related to any religious abode. If there is any reference to religion, it is fleeting, satirical and puerile in nature that can be easily discounted.

Lover and the beloved have met after the painful hours of separation, fellow rural people are dancing away the agony, and the beloved is in the unbroken glances of the lover. In another instance, lover returns from abroad after resigning to the excruciating pain of separation from a young beloved; or the love in is utter distress as the beloved has opted to part ways to marry another suitor—routine players, and same thematic concern in the songs. Every quality which is characteristic of human nature echoed through the amatory poetry of vagabonds. Theme of love which is flowing through the verses in the songs of the vagabonds is neither a discourse of a devotee or a platonic love above and beyond the physical needs of the body unlike the assumptions of apologetic and conservative defenders of Goliards. Endeavors to look for “pure love” in these songs by people with conservative morality shall bear no fruits. Love in these songs is addressed on the bases of natural drive, an instinctive need, and an intense psychological state of mind. This love can be called audacious and fearless, but nothing much can be known about the nature and moral character of the players who are carrying out this theme of love: poet, men, women, lover or beloved. All we need to comprehend is the fact there are only two predetermined characters in these songs: Goliards and women. Be it Phyllis or Flora, Lydia or Cecilia—all references are illusory and the essence of beloved shall remain the same. However, the identity of the poet continues to linger in the dark. And what identity a lover could be attributed to, except for being a lover—and this distinctiveness alone is enough. Nevertheless, a unique disposition of a lover can be determined based on the intensity of his emotions.

Only one song will be discussed with the theme of drinking and debauchery out of the many that were critically analyzed in advance. The reason for this selection is the fact that multiple artistic qualities have been gathered in this one single piece.

Now have a deep look at the chosen song. However, it is imperious to explain that while translating the song not only the literal meaning but the creative essence of the song was also kept intact. Hence, the regional and local characteristics in the song were replaced with the corresponding Indian characteristics. For example, there are three words in Urdu; Sawan, Bhadun, and Bahar to connotate the meaning of spring. And, for winters, due to its reference of jaded and cold nature in poetry was called Khizan. Moreover, the titles were given by myself. Therefore, the first title of the song is “ Sharmili Mohabbat” , in which the intent of the poet is not to show the amorous love of the poet but to reflect upon the maddening efflorescence of spring, much like the followin verse by Mir Taqi Mir.

Please nurse my aching soul

As the air reverberates with the onset of spring

Coy Love

Stand witness to the unfolding festivities of spring

Sweet are the nights and sweeter are the days

This alluring land is exuding the exuberance and lulling repose

As gone are the spells of autumn

But a gaping wound in my heart is the reminiscence of my love

A love that continues to ache and my eyes never run dry

So, how to get rid of affliction, and welcome solace!

Heart laden with grief and agony shall not efface the pain

If you don’t mend this broken soul

Have mercy, O, have mercy, nurse me with your love!

Foster your young heart in mine,

And blend in the hues of your love in mine!

Be a worshiper of love to embrace the secrets and limits of life!

A second song of pure spring follows:

(2)

Onset of Spring

The season of spring has returned,

The afflicted heart has been healed with the pleasure of your love

Gone and lost are the sad thoughts

And no restlessness remains intact

Golden rays of sun are spreading the light all over

And meadows are oozing forth the opulence of spring

Autumn season met the ultimate defeat

Heart is laced with the spring

And there is no pain left in the air

And every heart is intoxicated with the phantom love

—————–

Leave A Comment