Last month, Sneha Alexander attended the symposium Science Fiction Beyond the West: Futurity in African and Asian Contexts. Here she writes a summary of the day’s events.

Science Fiction Beyond the West: Futurity in African and Asian Contexts

Convened at SOAS, University of London, 12 July 2019

Last month Dr Tasnim Qutiat and July Blalack organised the conference Science Fiction Beyond the West: Futurity in African and Asian Contexts. This symposium reoriented discussion of Science Fiction to look beyond the West; engaging with decolonial theory, futurity and speculative fiction. As organiser July Blalack said in her welcoming remarks, “Speculative Fiction is a means to shift the conversation around the postcolonial world from ‘can they develop enough to catch up’ or ‘can they think scientifically’ to the worlds that help us understand or move beyond the present moment.” The decolonial imagination brings the sharpest insights to issues considered the domain of speculative fiction, making it clear that posthuman domains are not necessarily postracial, that the violence of ecocide is not inflicted on humanity equally, and that space can be more than a place of colonisation.In the words of organiser Dr Tasnim Qutiat, Science Fiction Beyond the West: Futurity in African and Asian Contexts centred around “the contested space of the future, how it is envisioned and theorized, and what this reveals about our present moment.” The programme speakers extended the critical and theoretical discussion about futurity in the early 21st century to regions which have tended to fall under a framework of exceptionalism and developmental rhetoric. Their talks explored how the futures imagined in African and Asian contexts play into social issues, explore cultural anxieties and experiment with alternative realities and possibilities.

Last month Dr Tasnim Qutiat and July Blalack organised the conference Science Fiction Beyond the West: Futurity in African and Asian Contexts. This symposium reoriented discussion of Science Fiction to look beyond the West; engaging with decolonial theory, futurity and speculative fiction. As organiser July Blalack said in her welcoming remarks, “Speculative Fiction is a means to shift the conversation around the postcolonial world from ‘can they develop enough to catch up’ or ‘can they think scientifically’ to the worlds that help us understand or move beyond the present moment.” The decolonial imagination brings the sharpest insights to issues considered the domain of speculative fiction, making it clear that posthuman domains are not necessarily postracial, that the violence of ecocide is not inflicted on humanity equally, and that space can be more than a place of colonisation.In the words of organiser Dr Tasnim Qutiat, Science Fiction Beyond the West: Futurity in African and Asian Contexts centred around “the contested space of the future, how it is envisioned and theorized, and what this reveals about our present moment.” The programme speakers extended the critical and theoretical discussion about futurity in the early 21st century to regions which have tended to fall under a framework of exceptionalism and developmental rhetoric. Their talks explored how the futures imagined in African and Asian contexts play into social issues, explore cultural anxieties and experiment with alternative realities and possibilities.

In her opening remarks for the conference, Dr Lindsey Moore (University of Lancaster) discussed Piercing Geometries’: Horizontal and Vertical Axes in Contemporary Arab Dystopia. Moore introduced the topic of contemporary speculative literature written in the Arab world, drawing attention to Utopia (Ahmed Khaled Towfik), Frankenstein in Baghdad (Ahmed Saadawi) and the short story collection, Palestine +100 (edited by Basma Ghalayini). Moore suggested that these texts demonstrate that many people in Arab world are intimately familiar with the concept of living under dystopia.

Moore questioned the concept of temporality – exploring the different ways writers imagine temporal existence and what that might mean for the writing of sci-fi beyond the West. She introduced the concept of ‘a dischronotopic imaginary’, which deals with a fraught sense of the present that compresses other temporalities into it. She then proposed to interrogate this temporal struggle in terms of the horizontal space of the street, or square, and the vertical space of the tunnel. She discussed the relevance of these geographies both regarding the texts she proposed to talk about and the events of the Arab Spring.

Photo by Phil Pearson on Unsplash

Moore’s exploration of the horizontal axis of dystopia questioned what she called the horizontal life spirit’ and the ways we attach the future to the past. Moore challenged purely linear and horizontal understandings of temporality as she drew attention to the indelible traces traces that remain from what was, even after processes of erasure. In terms of vertical geographies, Moore described the towering apartment blocks of the French banlieues as a vertical dystopia lived by the marginalised, drawing parallels with the Grenfell tower fire. She suggested that vertical struggles can be clearly mapped on urban space in France and the UK; in that the higher the story you live on the more likely you are to be on state assistance. Moore sees this as a structural result of biopower, the culmination of which ends in the ‘cement supercolony’. She ventured that the banlieue is in fact representative of the afterlife of empire, imagining French social housing as a rationalisation of space and time.

Moore astutely pinpointed the racialised geographies of threat, citing Larissa Sansour’s co-directed work ‘In Vitro’ made with Soren Lind. In this film, Sansour uses a split screen to show the parallel worlds of Palestine and Israel, here literally occupying the same space – reflecting the reality of contemporary Palestine; where one can see over the border but cannot travel beyond it. Moore then questioned which is the utopia and which is the dystopia, citing Thomas More’s Utopia where utopia is demonstrated to exist relationally rather than objectively. Drawing back to themes central in science fiction writing, Moore asks how questions of cloning, hybridity and mass productions are, in fact, reiterations of questions about heritage and perceived authenticity. Moore ended her talk by discussing Kader Attia’s installation Reflecting Memory, suggesting the productive estrangement of these texts in which the world is mirrored back to us and compressed into this tensile present. In this respect, Moore offered new ways of thinking about temporality, especially when looking at science fiction beyond the West.

The first panel, The Body Politic, the Alien, the Posthuman, the Other, brought together Liam Wilby (University of Leeds), Lyu Guangzhou (University College London), Kerry Mackereth (University of Cambridge) and was chaired by July Blalack (SOAS).

Wilby’s talk, “Anthony Joseph’s Autopoietic Fiction: Addressing the Territory and not the Map in The African Origins of UFOs,” examined the structure of Joseph’s novel using the idea of ‘self-organising’ systems proposed by Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela in Autopoesis and Cognition. Wilby argued that in The African Origins of UFOs, Joseph organises archetypal experiences and vignettes in a recursive spiral structure that reflects the self-organising structure of living systems themselves. Wilby suggested that it is through the interactions of these systems that new forms of consciousness can emerge. He drew on Sylvia Wynter’s reconceptualization of the human in relation to modernity, blackness and urban space and demonstrated how new literary consciousness come into being in Joseph’s text when Caribbean literary tradition interacts with Afrofuturist imaginaries. Wilby concluded his talk by aligning Kamau Brathwaite’s theories on the reproductive potential of language with Joseph’s project of reconfiguring the afrofuturist imaginary of rebirth and blackness.

Guangzhao’s talk, “Dark Forest or Grand Central: The Self-Other Polarity in Liu Cixin and Arthur C. Clarke’s Science Fiction” discussed the opposing conceptions of the Self-Other polarity in the work of Cixin and Clarke. He began by drawing attention to the similarities shared by the two author, such as: a commitment to world building, interest in scientism and preoccupation with the sublime. However, Guangzhao argued that for Cixin, there is no hierarchical privilege inherent in the Self-Other polarity. By contrast, Guangzhao drew attention to the way in which Clarke’s fiction justifies hierarchy in terms of rationality – citing the novel “Childhood’s End”, where the inferior human race becomes extinct when the children are assimilated into the Overmind. Guangzhao positioned the central principle of Cixin’s The Dark Forest – that that universe is constant and designed to expand (as survival is the drive of civilisation) – as at odds with Clarke. Guangzhao thus concluded that while for Clarke hierarchy is justified by rationality, that can never be the case for Cixin.

Guangzhao’s talk, “Dark Forest or Grand Central: The Self-Other Polarity in Liu Cixin and Arthur C. Clarke’s Science Fiction” discussed the opposing conceptions of the Self-Other polarity in the work of Cixin and Clarke. He began by drawing attention to the similarities shared by the two author, such as: a commitment to world building, interest in scientism and preoccupation with the sublime. However, Guangzhao argued that for Cixin, there is no hierarchical privilege inherent in the Self-Other polarity. By contrast, Guangzhao drew attention to the way in which Clarke’s fiction justifies hierarchy in terms of rationality – citing the novel “Childhood’s End”, where the inferior human race becomes extinct when the children are assimilated into the Overmind. Guangzhao positioned the central principle of Cixin’s The Dark Forest – that that universe is constant and designed to expand (as survival is the drive of civilisation) – as at odds with Clarke. Guangzhao thus concluded that while for Clarke hierarchy is justified by rationality, that can never be the case for Cixin.

Mackereth’s talk, “Everybody Sees You as Human: Ex Machina and Ghost in the Shell” discussed how the concept of ‘passing’ as human in Science Fiction films is tied to our understanding of racial passing. Mackereth suggested that the anxiety of passing is a deeply racialised compulsion to know the truth of another’s body. Citing Bhaba, Stoler and Ahmed, Mackereth questioned what it might mean to produce a non-human ‘human’ subject under racialised structures of power. Mackereth then discussed the films Ex Machina and Ghost in the Shell, drawing attention to white-washing in Hollywood and the racial politics that structure these films. Mackereth cited Sara Ahmed’s understanding of ‘passing’, in which it serves to stabilise pre-existing power structures as white and racialised bodies are considered fixed points between which the Othered body can move. She then gestured to the work of critical race theorists who problematised post-human theory, demonstrating that – in the West – the post-human body often reinscribes white, Western notions of a fixed and sovereign humanity. Mackereth then examined the films through the lenses of Aesthetics, Somatics and Erotics, demonstrating the inherent biopolitics that cause both racialised bodies and non-human bodies to be imagined as insensate.

Mackereth’s talk, “Everybody Sees You as Human: Ex Machina and Ghost in the Shell” discussed how the concept of ‘passing’ as human in Science Fiction films is tied to our understanding of racial passing. Mackereth suggested that the anxiety of passing is a deeply racialised compulsion to know the truth of another’s body. Citing Bhaba, Stoler and Ahmed, Mackereth questioned what it might mean to produce a non-human ‘human’ subject under racialised structures of power. Mackereth then discussed the films Ex Machina and Ghost in the Shell, drawing attention to white-washing in Hollywood and the racial politics that structure these films. Mackereth cited Sara Ahmed’s understanding of ‘passing’, in which it serves to stabilise pre-existing power structures as white and racialised bodies are considered fixed points between which the Othered body can move. She then gestured to the work of critical race theorists who problematised post-human theory, demonstrating that – in the West – the post-human body often reinscribes white, Western notions of a fixed and sovereign humanity. Mackereth then examined the films through the lenses of Aesthetics, Somatics and Erotics, demonstrating the inherent biopolitics that cause both racialised bodies and non-human bodies to be imagined as insensate.

The second panel, Decolonial Histories and the Future, brought together Annie Webster (SOAS), Ella Elbaz (Stanford), Pius Vögele (University of Basel) and Dr Edna Bonhomme (Max Planck Institute or the History of Science). This panel was chaired by Dr Tasnim Qutait.

Webster’s talk, “Ruins of the Future: On The Possibility of Life Amidst the Atlal,” discussed the tradition of “ruin-gazing” as a generative act for narration, story and trope. Opening with a discussion of The Mushroom at the End of the World (Anna Tsing), Webster highlights the notion that progress implies ruination. She then complicates this narrative further by citing Sara Pursley’s Familiar Futures, in which attempts to pursue a democratic future are revealed to have neocolonial implications. Webster then discussed imaginaries of Iraq after the war and suggested that predictions became a laboratory for “familiar futures” instead of anti-colonial progress. Webster cited the science fiction collection Iraq + 100, as a colonial encounter in literary terms. However, she also argued that Iraq + 100 constructed unfamiliar futures by presenting a cacophony of temporal patterns. In addition to this, she argued that the book can work a means to engage with colonial ruins without it becoming poverty porn or war porn. Webster also raised the difficulties of asking Iraqi writers to speak of the future rather than the past, before asserting the importance of recognising and writing science fiction in conversation with traditions of the Atlal.

Webster’s talk, “Ruins of the Future: On The Possibility of Life Amidst the Atlal,” discussed the tradition of “ruin-gazing” as a generative act for narration, story and trope. Opening with a discussion of The Mushroom at the End of the World (Anna Tsing), Webster highlights the notion that progress implies ruination. She then complicates this narrative further by citing Sara Pursley’s Familiar Futures, in which attempts to pursue a democratic future are revealed to have neocolonial implications. Webster then discussed imaginaries of Iraq after the war and suggested that predictions became a laboratory for “familiar futures” instead of anti-colonial progress. Webster cited the science fiction collection Iraq + 100, as a colonial encounter in literary terms. However, she also argued that Iraq + 100 constructed unfamiliar futures by presenting a cacophony of temporal patterns. In addition to this, she argued that the book can work a means to engage with colonial ruins without it becoming poverty porn or war porn. Webster also raised the difficulties of asking Iraqi writers to speak of the future rather than the past, before asserting the importance of recognising and writing science fiction in conversation with traditions of the Atlal.

Elbaz’s talk, “Can the Future Speak? The Rise of the Palestinian Futurist Novel and its Folklorist Roots,” contested the the ways that non-realistic narratives are imagined as antithetical to Arab novels. Elbaz challenged the concept of science fiction writing as new to Arab literary traditions and interrogated the reasons for Arab science fiction currently receiving publicity in the West. She proposed to interrogate Western fascinations with Arabic futurism by re-examining Palestinian writing, then drew connections between science fiction and long traditions of non-realistic Arab writing in folktales and popular fiction. She also asked what it might mean to speak for the future subaltern in the case of Palestine, interrogating how Palestinians could speak their future and what that might mean. Using the example of Azem’s novel Sifr al-ikhtifa, Elbaz draws attention to how Palestinian voices are appropriated in the text, with one diary of a disappeared Palestinian being translated into Hebrew. Here erasure translates from our past and present to an imagined future; the future subaltern cannot speak.

Elbaz’s talk, “Can the Future Speak? The Rise of the Palestinian Futurist Novel and its Folklorist Roots,” contested the the ways that non-realistic narratives are imagined as antithetical to Arab novels. Elbaz challenged the concept of science fiction writing as new to Arab literary traditions and interrogated the reasons for Arab science fiction currently receiving publicity in the West. She proposed to interrogate Western fascinations with Arabic futurism by re-examining Palestinian writing, then drew connections between science fiction and long traditions of non-realistic Arab writing in folktales and popular fiction. She also asked what it might mean to speak for the future subaltern in the case of Palestine, interrogating how Palestinians could speak their future and what that might mean. Using the example of Azem’s novel Sifr al-ikhtifa, Elbaz draws attention to how Palestinian voices are appropriated in the text, with one diary of a disappeared Palestinian being translated into Hebrew. Here erasure translates from our past and present to an imagined future; the future subaltern cannot speak.

Bonhomme’s talk, “Defying Colonialism: Speculative (and Liberated) Fiction in Early Twentieth Century Africa,” interrogated the ways in which African people articulated colonialism through speculative fiction. Bonhomme drew attention to the role of Western medical science as a tragic feature of colonialism due to its biopolitical power. Using Cameroon as her case study, Bonhomme posited that healing, witchcraft and local religions were the start of futuristic imaginings, produced as a direct response to the colonial threat. Bonhomme argued that Cameroonian fiction of that era represents white colonizers as alien/ghosts presences in the land and positioned these fictions with the canon of Science Fiction. Bonhomme also drew attention to the practices of so-called witchcraft in opposition to Western medicine, reiterating that biomedicine dovetailed with the colonial projects and should be interrogated as such. By looking at the articulation of anti-colonialism through medicine and bio-political power, Bonhomme encouraged us to look for Science Fiction writing in the past, as a tool for imagining the future that is now our present.

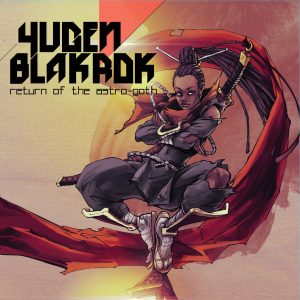

Vögele’s talk, “Stargates to Parallel Universes: Yugen Blakrok’s Afrofuturistic Sonic Fictions,” discussed the lyrics, music and graphics created by singer Yugen Blakrok. Vögele discussed the American jazz composer Sun Ra and his influence of afrofuturism in terms of ‘sonic fictions’ as opposed to literary ones. Vögele read Ra’s work through Afrofuturism and Black Sound Studies (Erik Steinskog), then began to draw connections between the genre of HipHop and Afrofuturism. Vögele suggested that while HipHop retrofits, re-functions and misuses techno-commodities to produce new art forms, literary Afrofuturism retrofits, re-functions and reuses traditions from the African continent to tell stories in new ways. Vögele positioned Blakrok within a continuum of artists who used afrofuturist imagery as part of their sonic projects, aligning Blakrok’s latest album with Afrika Bambaata and Soul Sonic Force: Planet Rock the Album and Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet. He demonstrated how Blakrok’s understanding of sonic afrofuturism uses the imagery of her music videos, alongside the lyrics, to connect nature, religion and space – layering metaphors from cosmologies of the Dogon and the Draxaya mythology to produce a dense and important sonic fiction.

Vögele’s talk, “Stargates to Parallel Universes: Yugen Blakrok’s Afrofuturistic Sonic Fictions,” discussed the lyrics, music and graphics created by singer Yugen Blakrok. Vögele discussed the American jazz composer Sun Ra and his influence of afrofuturism in terms of ‘sonic fictions’ as opposed to literary ones. Vögele read Ra’s work through Afrofuturism and Black Sound Studies (Erik Steinskog), then began to draw connections between the genre of HipHop and Afrofuturism. Vögele suggested that while HipHop retrofits, re-functions and misuses techno-commodities to produce new art forms, literary Afrofuturism retrofits, re-functions and reuses traditions from the African continent to tell stories in new ways. Vögele positioned Blakrok within a continuum of artists who used afrofuturist imagery as part of their sonic projects, aligning Blakrok’s latest album with Afrika Bambaata and Soul Sonic Force: Planet Rock the Album and Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet. He demonstrated how Blakrok’s understanding of sonic afrofuturism uses the imagery of her music videos, alongside the lyrics, to connect nature, religion and space – layering metaphors from cosmologies of the Dogon and the Draxaya mythology to produce a dense and important sonic fiction.

The third panel, A Wilting Planet, Ecology and Dystopia, brought together Chen Ma (SOAS), Ouissal Harize (Durham University), Tabea Wilkes (SOAS) and Dr Emilia Terracciano. This panel was chaired by Dr Nora Parr.

Ma’s talk, Waste Tide: “Ecoambiguity, Failure, and Emotional Propaganda Effect,” discussed the sci-fi realism of Chen Quifan’s novel Waste Tide (1981). The novel is set in 2020, against the backdrop of an e-waste crisis in China’s Guiyu island. Ma interrogated the novel alongside ‘Plastic China’, a recent documentary titled which drew attention to China’s plastic waste crisis. After emphasising Waste Tide’s direct relation to China’s ecological crisis, Ma examined the novel through Li Hua’s understanding of ‘slow violence’. Ma drew attention to the ecological potential of the text, in particular the disjunct between the workers at the e-waste plant, whose lives are destroyed by this climate crisis but whose work directly contributes to ecological devastation. Ma described this phenomenon using Karen Thornber’s term ‘eco-ambiguity’. She then demonstrated how the conflicts of Chinese national identity and struggle between past and future are played out on the female body of waste-worker Mimi, drawing attention to emotional propaganda in Chinese Science Fiction and its role in narrating the climate crisis.

Ma’s talk, Waste Tide: “Ecoambiguity, Failure, and Emotional Propaganda Effect,” discussed the sci-fi realism of Chen Quifan’s novel Waste Tide (1981). The novel is set in 2020, against the backdrop of an e-waste crisis in China’s Guiyu island. Ma interrogated the novel alongside ‘Plastic China’, a recent documentary titled which drew attention to China’s plastic waste crisis. After emphasising Waste Tide’s direct relation to China’s ecological crisis, Ma examined the novel through Li Hua’s understanding of ‘slow violence’. Ma drew attention to the ecological potential of the text, in particular the disjunct between the workers at the e-waste plant, whose lives are destroyed by this climate crisis but whose work directly contributes to ecological devastation. Ma described this phenomenon using Karen Thornber’s term ‘eco-ambiguity’. She then demonstrated how the conflicts of Chinese national identity and struggle between past and future are played out on the female body of waste-worker Mimi, drawing attention to emotional propaganda in Chinese Science Fiction and its role in narrating the climate crisis.

Harize’s talk, “The Promised Land in the Imaginary of the Anthropocene: Palestine in The Second War of the Dog and Larissa Sansour’s Trilogy of Science Fiction” contested that readers of Palestine +100 would regard science fiction as disconnection from contemporary struggles. Elbaz posited science fiction as both a mode of engagement and act of resistance by those people who were continually cast as alien in their homeland. She discussed the novel The Second War of the Dog (Ibrahim Nasrallah) in which Nasrallah complicates the differences between self/other or human/posthuman. Harize tied this to cultural ambiguities that accompany colonial expansion then expanded on the link between colonial alienation and futuristic imaginaries by drawing on Larissa Sansour’s film The Space Exodus. Harize connects the death of the planet in The Space Exodus with Palestine (the Promised Land) and wondered whether the promised land will end up as nothing more than a futuristic wasteland. By aligning the dread of dispersal in science fiction with that of colonial diasporic subjects, Harize demonstrated how science fiction in Palestine is a useful tool for the present even as it imagines the future.

Harize’s talk, “The Promised Land in the Imaginary of the Anthropocene: Palestine in The Second War of the Dog and Larissa Sansour’s Trilogy of Science Fiction” contested that readers of Palestine +100 would regard science fiction as disconnection from contemporary struggles. Elbaz posited science fiction as both a mode of engagement and act of resistance by those people who were continually cast as alien in their homeland. She discussed the novel The Second War of the Dog (Ibrahim Nasrallah) in which Nasrallah complicates the differences between self/other or human/posthuman. Harize tied this to cultural ambiguities that accompany colonial expansion then expanded on the link between colonial alienation and futuristic imaginaries by drawing on Larissa Sansour’s film The Space Exodus. Harize connects the death of the planet in The Space Exodus with Palestine (the Promised Land) and wondered whether the promised land will end up as nothing more than a futuristic wasteland. By aligning the dread of dispersal in science fiction with that of colonial diasporic subjects, Harize demonstrated how science fiction in Palestine is a useful tool for the present even as it imagines the future.

Wilkes’ talk “Ecocriticism in African Science Fiction; Using Afrofuturism to inform the speculative fiction of environmental policy” discussed how the study of law can interact with literature in an African context. Wilkes positioned Ngugi Wa Thiong’o and Chinua Achebe’s as authors who wrote about issues that are now being tackled in social science and development policy. She described the concept of ‘backcasting’, in which the future is imagined and the predicted disasters are then reverse engineered. Wilkes then discussed this process of ‘backcasting’ in terms of speculative fiction, citing Lagoon (Nnedi Okrafor) and The Old Drift (Namwali Serpell), Both of these novels were visibly influenced by the Niger Delta Oil Spill and, in both, the non-human world fights against harmful human infrastructure. Wilkes went on to draw attention to how environmental international law is created around white Western ideas of humanity. She questioned what a human right to environment might mean, and what could constitute legal personhood. By reading African Science Fiction alongside International Law, Wilkes suggested that environmental law can be reoriented to privilege the non-white, non-Western and even non-human (vegatal or water-based) subjects.

Wilkes’ talk “Ecocriticism in African Science Fiction; Using Afrofuturism to inform the speculative fiction of environmental policy” discussed how the study of law can interact with literature in an African context. Wilkes positioned Ngugi Wa Thiong’o and Chinua Achebe’s as authors who wrote about issues that are now being tackled in social science and development policy. She described the concept of ‘backcasting’, in which the future is imagined and the predicted disasters are then reverse engineered. Wilkes then discussed this process of ‘backcasting’ in terms of speculative fiction, citing Lagoon (Nnedi Okrafor) and The Old Drift (Namwali Serpell), Both of these novels were visibly influenced by the Niger Delta Oil Spill and, in both, the non-human world fights against harmful human infrastructure. Wilkes went on to draw attention to how environmental international law is created around white Western ideas of humanity. She questioned what a human right to environment might mean, and what could constitute legal personhood. By reading African Science Fiction alongside International Law, Wilkes suggested that environmental law can be reoriented to privilege the non-white, non-Western and even non-human (vegatal or water-based) subjects.

Pandurang Khankhoje growing maize, photo from ScrollIn

Terracciano’s talk, “Maiz Granada: Weaponising the Future Vegetal World” discussed her concept of “Agrofuturism,” exploring science fiction through the lens of food security. Terracciano drew attention to the fact that the word “diaspora” derives from botanical origins, aligning the economic and political transformations that came from plantations with imaginaries of food development. Citing the scientific agriculturism practiced by agrarian communists in Venezula as well as the bioengineering of hybrid seeds in Mexico, Terraciano challenged our understanding of food development. She gave the example of the cross-cultural alliances fostered by Pandurang Khankhoje (who fled India for Mexico at the end of WWI) to demonstrate how the imaginaries and technologies essential to food development emerged beyond the West.

The final panel Beyond Earth, Liberated Space or the Final Colonial Frontier? brought together Dr Jörg Matthias Determann (Virginia Commonwealth University, Qatar), Nat Muller (Birmingham City University) and Rachel Hill (Goldsmiths University). This panel was chaired by Dr Sinead Murphy.

Determann’s talk Envisioning Extraterrestrial Life in Muslim Science Fiction revealed the relationship between Islamic scripture and Science Fiction, as well as discussing Muslim majority states’ attitudes towards Science Fiction. Determann acknowledged that the Muslim world is not often associated with the genre of Science Fiction. He cited religion, repression, and rote learning as being blamed for a perceived lack of future-oriented imagination. However, Determann contested that even extremely authoritarian Muslim majority countries have been home to the pursuit of imaginative pursuits of knowledge, in particular astrobiology. Determann argued that the Islamic tradition has in fact nurtured, rather than repressed, conceptions of extraterrestrial life. He drew attention to how the Qur’an often refers to Allah as “lord of the worlds” and then explained that Muslim scholar went on to use such phrases as a basis for both astrobiological research and the writing of science fiction. Determann also suggested that Muslim majority governments supported a great deal of scientic research and writing, while politically taboo topics forced authors towards science fiction; contemporary politics were reconfigured through science fiction novels set on different planets or in future time zones. Determann closed his talk with some of humanity’s biggest questions: Are we alone in the universe? And what would it mean for one of our greatest faiths, if we are not?

Rachid Karameh International Exhibition Centre. Photo: Lode Vermeiren, Flickr

Nat Muller’s talk Fly me to the Moon? Retrofuturism and the Ruins of Modernity in Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s A Space Museum discussed the Retrofuturist movement, which centres imaginations of the future that have been created in an earlier time. Muller discussed the Rachid Karami International Fair in Tripoli, whose building was disrupted, leaving in lying in ruins to this day. Architect Oscar Niemeyer was commissioned to design the Rachid Karami International Fair in 1963 but it was discontinued with the onset of civil war in 1975. Muller described this as a failed nation building as well as a vision of the future that was never fully realised. Muller discussed Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s project A Space Museum (designed in the ruins of the Rachid Karami International Fair) as a contemporary iteration of identity and futurism, as unrealised potential from the past is brought to life by an interaction with our present. Muller suggested that this created a loop of sorts, paralleled by the work itself where both historical and contemporary video clips are played continuously, rejecting organisation by chronological time. Muller posited that the Space Museum can therefore be viewed as a historical monument that recovers time rather than material objects, creating the possibility of the museum as a retrofuturist space.

Hill’s talk “Bind the stars with the drums. There would be dancing”: Decolonial Imaginaries of Space Exploration brought into conversation New Space technologies, contemporary space law and decolonial science fiction. Hill outlined what constituted New Space technologies – these incluse rockets and Space-X designs as well as the speculative development of asteroid and lunar mining. Hill explained that the lure felt by the ‘astro-peneurs’ is the prospect of potentially infinite resources and thus is a primarily capitalist project. She then demonstrated that, when imagined this way, the New Space imperative aligns human life with capital. Hill questioned how we arrived at this juncture, drawing attention to the efforts of Group 77, who tried to make resources extracted in outer space the property of the public. This would have developed a completely different relationship between humankind and space exploration and exploitation. However the failure of these attempts was followed by the The Space Act (ratified in 2015) which encouraged space exploitation. As a complement to this, Hill positioned the work of Group 77 as an ‘undiscarded past’ (Ernst Bloch) – a possible avenue as yet untaken but not completely obliterated. Hill then introduced the novel Nigerians in Space (Deji Bryce Olukotun) and read it alongside 1964 Zambian space programme that aimed to get Zambia to the moon before the USSR or US. Hill drew together these diverging imaginaries of outer space as a locus of radical decolonial possibilities, undiscarded pasts that could yet become the future.

Hill’s talk “Bind the stars with the drums. There would be dancing”: Decolonial Imaginaries of Space Exploration brought into conversation New Space technologies, contemporary space law and decolonial science fiction. Hill outlined what constituted New Space technologies – these incluse rockets and Space-X designs as well as the speculative development of asteroid and lunar mining. Hill explained that the lure felt by the ‘astro-peneurs’ is the prospect of potentially infinite resources and thus is a primarily capitalist project. She then demonstrated that, when imagined this way, the New Space imperative aligns human life with capital. Hill questioned how we arrived at this juncture, drawing attention to the efforts of Group 77, who tried to make resources extracted in outer space the property of the public. This would have developed a completely different relationship between humankind and space exploration and exploitation. However the failure of these attempts was followed by the The Space Act (ratified in 2015) which encouraged space exploitation. As a complement to this, Hill positioned the work of Group 77 as an ‘undiscarded past’ (Ernst Bloch) – a possible avenue as yet untaken but not completely obliterated. Hill then introduced the novel Nigerians in Space (Deji Bryce Olukotun) and read it alongside 1964 Zambian space programme that aimed to get Zambia to the moon before the USSR or US. Hill drew together these diverging imaginaries of outer space as a locus of radical decolonial possibilities, undiscarded pasts that could yet become the future.

Leave A Comment