Roanne Kantor is Lecturer in Comparative Literature at Stanford University. She is a MULOSIGE Critical Friend and gave the talk “A Case of Exploding Markets” for the project on the 7th June 2017.

A Case of Exploding Markets: Latin American and South Asian Literary “Booms” in a Comparative Perspective

MULOSIGE’s Dr. Fatima Burney sat with Dr. Roanne Kantor to talk about her upcoming book “Even if

you Gain the World: The Rise of South Asian literature in Light of Latin America”. Dr. Kantor is an

assistant professor in the Department of English at Stanford University. She received her Ph.D. in

Comparative Literature at University of Texas, Austin and has taught at Harvard University, Boston

University, Brandeis, and the University of Texas, Austin. She gave a talk titled “A Case of Exploding

Markets: Latin American and South Asian Literary “Booms” in a Comparative Perspective” for

MULOSIGE at SOAS in 2017. This interview is excerpted from a conversation they had in 2017.You can listen to the full MULOSIGE podcast with Professor Kantor here.

Roanne Kantor at the Jaipur Literary Festival

FB: Hello and welcome to MULOSIGE’s podcast series. My name is Fatima Burney and I’m sitting with Roanne Kantor to talk about a talk she recently gave for us at SOAS and her upcoming book, Even If You Gain the World: The Rise of South Asian Literature in Light of Latin America. Thank you Roanne for being here.

My first question for you will be: where did you come up with this title? It’s such a beautiful, evocative title.

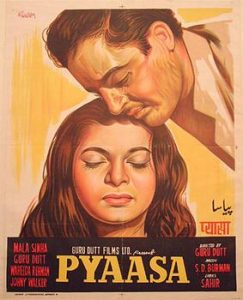

RK: Well, first of all, thank you for having me, I really enjoyed giving this talk. I’ll answer the title question in two parts because of course it has a main title and then a subtitle. Some of you may actually recognise the main title “Even If You Gain the World”, it’s a particular translation of “Yeh Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaye to Kya Hai”, the old song from Pyaasa. If you remember that film there’s this incredible scene in which the poet walks into his own memorialisation service, having become a sort of posthumous, or ersatz posthumous, star with his poetry – poetry that he couldn’t give away during his lifetime. He sings this song as a way of condemning the kind of commercialisation of his social poetry. So I think that this move of condemning what looks like on the surface to be success, also characterises what so many of us are feeling about South Asian Anglophone literature now. Yes, we have succeeded, we have “gained the world” but we’ve also lost something and the thing that we’ve lost is hard to articulate – and that’s the arc of the book.

RK: Well, first of all, thank you for having me, I really enjoyed giving this talk. I’ll answer the title question in two parts because of course it has a main title and then a subtitle. Some of you may actually recognise the main title “Even If You Gain the World”, it’s a particular translation of “Yeh Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaye to Kya Hai”, the old song from Pyaasa. If you remember that film there’s this incredible scene in which the poet walks into his own memorialisation service, having become a sort of posthumous, or ersatz posthumous, star with his poetry – poetry that he couldn’t give away during his lifetime. He sings this song as a way of condemning the kind of commercialisation of his social poetry. So I think that this move of condemning what looks like on the surface to be success, also characterises what so many of us are feeling about South Asian Anglophone literature now. Yes, we have succeeded, we have “gained the world” but we’ve also lost something and the thing that we’ve lost is hard to articulate – and that’s the arc of the book.

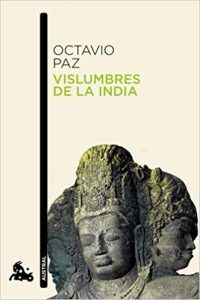

Now the second part, the subtitle, in light of Latin America, is a re-appropriation of the translated title Octavio Paz’s Vislumbres de la India. Now Vislumbres de la India interestingly enough does not mean “In the light of India”. It’s sort of a mistranslation. It means “glimmers of India”, as if India is a light source from which we get little tiny threads of light. Instead, “In light of India” seems to suggest that India is a lightsource that sheds light onto something else, so I wanted to reverse that because I think that the project in general is, in a sense – certainly this talk in particular – is about Latin America instead, shedding light on a phenomenon that emerges out of India and other parts of South Asia.

Now the second part, the subtitle, in light of Latin America, is a re-appropriation of the translated title Octavio Paz’s Vislumbres de la India. Now Vislumbres de la India interestingly enough does not mean “In the light of India”. It’s sort of a mistranslation. It means “glimmers of India”, as if India is a light source from which we get little tiny threads of light. Instead, “In light of India” seems to suggest that India is a lightsource that sheds light onto something else, so I wanted to reverse that because I think that the project in general is, in a sense – certainly this talk in particular – is about Latin America instead, shedding light on a phenomenon that emerges out of India and other parts of South Asia.

FB: That’s really beautiful. So both parts of the title are shining light onto each other.

RK: Yes!

FB: I think you’re right, I think it is tricky to think about the commodification of literature and markets for literature in literary studies. It can become contested terrain because so often what we think becomes canonical – what stands against the tests of time – is what stands against the markets.

So, what brought you to this project? What motivated you to think about representations of markets and the effects of markets?

“There is no authentic way of dealing with a market. So we’re invoking that term even when we don’t use it.”

RK: That’s a great question. Actually again it was the first part of the project that brought me towards this later discussion of markets because what we forget is that these earlier connections that I look at (at the beginning of the book) between individual authors who are travelling for the first time to new geographies that they did not have a previous connection to, these authors were not travelling out of personal interest. They were travelling for political reasons and often for economic reasons. They were working and that’s what brought them into these new atmospheres and opened up these new possibilities for their writing. So there has always been an economic aspect to these kind of circulations but it happened previously at the level of the individual. How does an author make money in a context where you can’t have just a literary job, you have to also have a day job.

FB: What a timely question.

Editorial drawing by Vijay Nambisan, an Anglophone poet and journalist from the 1990s. From the Bombay Poets Archive at Cornell.

RK: Oh exactly! And then in later years that question becomes what happens to your writing and it’s authenticity perhaps, when in fact you can make all your money being a writer, when you can make a lot of money by being a writer! Where you can have new stories just about how much money you made in your advance. So, that is a different question but a related question.

FB: So I’m glad that you brought up the term authenticity because it seems to me that it is at the heart of some of the anxieties around talking about the market. Can you say a little bit more about how you’re playing with the word authenticity? What does that mean for this project and for these writers?

RK: Authenticity is a word that we don’t want to use, we actually feel very uncomfortable with it. Yet when we’re talking about how authors address the market or how they “make hay’ out of a booming market—and automatically whatever it is that they do in order to take advantage of that market is inauthentic—often we’re talking around a concept that looks like authenticity. There is no authentic way of dealing with the market. So we’re invoking that term even when we don’t use it. I think another term that we, as literary scholars, do not want to use and yet we are imputing all the time is … intention!

Everybody who is a literary scholar knows that you can’t talk about authorial intention. But when we talk about the way that certain tropes in literature address a market, we are invoking intention. We assume that those tropes are put in with an intention to capture the market which, firstly, assumes that authors have a lot more control over the market than they really do. I would say that most authors are surprised by what catches in their writing and the fact that they are so successful. Secondly, this idea that intention is not something that we are supposed to talk about, yet we can invoke it through a back door is awkward. Whenever we want to talk about a term, it is healthier to just bring it up: “OK, this is what we are talking about. I feel uncomfortable, you feel uncomfortable.” And authenticity is especially being invoked often around discussions on language and what language we are composing in. Yet it is not being spoken of as such. I think it would bring a lot more power and precision to the conversation if we just admitted that that’s what we want to talk about.

FB: What insights does this work bring to postcolonial studies and studies on South-South relations and Third Worldism more broadly? On the one hand, it’s exciting to imagine that we can talk about the relationship between South Asia and Latin America without Europe as a mediator, but this work seems to involve a great many different global actors.

RK: That’s a huge question and to that I want to add one more term, which is Comparative Literature which is, of course is the field that I was trained in. Natalie Melas has a lovely book called All The Difference in the World in which she digs into the history of comparative literature as comparative. She seems to be asking “what do we do and risk when we engage in comparison”. That is a question that is lurking within postcolonial studies and has erupted into different kinds of controversies about how we continue to use this term and how it’s useful for us as an analytic. This is particularly sharp in the work that I do because Latin America is so frequently excluded from the postcolonial – and for reasons that can be really coherent! Ania Loomba does a really good job of synthesizing how this exclusion happened.

But the problem for me is that there are still moments, even if we don’t want to talk about Latin America as postcolonial, in which comparison is essential and we can’t just simply look at the differences in language of composition. Spanish is not only literally a different language, it’s a completely different linguistic situation. We cannot always say that because a difference exists, comparison is not possible. We have to proceed with extreme caution. And I try to do that. But there’s also an importance in insisting that the work can be done and we’re going to find a way to do it. As a comparatist, that’s my plug for my method. At this moment when a lot of us are asking ourselves what the future of postcolonial studies might be, especially in literature, we may need to reapproach how we think about comparison and really dig into the work of what we’re going to do with difference, because difference will always emerge.

FB: From what you’re saying it also sounds like postcolonial studies and comparative literature departments are in themselves feeding off of and feeding into some of the boom cycles that you’ve described. Do you see that happening?

An image from Vislumbres, a short-lived magazine set up to explore Iberio-Indian connections in the wake of Paz.

RK: Yes, and actually in different ways than we often conceptualize. If you look at some of the literature that’s out there, you will see, in different ways, scholars being admirably self-reflexive about our own role in promoting certain types of literature and how that cycles back into markets. We too are being commodified. Our work is being commodified and that is tremendously uncomfortable. But there are other dimensions which I have not seen explored which would be really interesting for future research.

Most prominently, I think about the institution where I got my Ph.D.—University of Texas, Austin—and the role that it played in bringing in authors from Latin America, South Asia, and Anglophone authors from Africa, and having these authors gather at UT and meet each other, supporting them through visiting fellowships and different kinds of professorial positions. What we see is actually a huge growth not just in authors from the global South but in authors generally speaking, support themselves professionally in part by teaching more and more. You see authors who are also professors of creative writing. And that institutional impact, in some ways, is a lot more significant than our impact as individual scholars and what we teach. They work together. But one aspect has been perhaps over studied while the other could be researched better within our field.

And there’s actually a lot of material and documentation of such institutional support. For example, if we look closely at the Latin American case, there were events like the 1965 Latin American year at Cornell. We have all of the records of those events somewhere in institutional archives. You just have to go through and find them. And those events were cosponsored by, for example, elements of the government, by the state department, and by all these different, really interesting funding streams that were deeply imbricated in geopolitics of the time. You can go and read the letters that describe exactly how much money each department is going to pay for hiring somebody like Octovia Paz. And while that kind of work is tedious, it’s really important. And it would yield a completely different kind of insight about how institutions function to promote boom phenomena, and how they function not in a vacuum but as part of much larger systems.

FB: You’ve tended to primarily discuss novels when describing the phenomena of boom cycles. What about poetry? Does poetic writing also go through boom cycles in the same way?

RK: That’s a good question. I think my short answer is no, unfortunately. I sort of imagine the arc of the book project to actually be the dreams of the poet and the reality of the novelist. So the death of this different kind of concept of world literature, which is mediated through poetry and which honors the uniqueness almost fetishized, unique untranslatability of a literary tradition in a specific non-Anglophone language, versus the Novel, which sort of capitulates to global aesthetics in a single language. There does not seem to be as robust a market for poetry, in general. This is true of the Anglophone market but perhaps not necessarily true of other markets. Poetry is not as robust in English as compared to the novel and it doesn’t seem to succeed easily, specifically in boom situations, because boom situations depend on a certain flattening and easy understanding across cultural contexts. Many people believe that poetry is not just linguistically rooted, but perhaps more culturally rooted because so many of its meanings are submerged beneath many different layers. That doesn’t mean that poetry hasn’t become what we might call world literature. Obviously it has, but I think our particular moment is not friendly to poetry on a number of levels.

FB: It’s interesting that you should use the word “flattening” to describe this phenomenon. Would you say that in tracing this flattening processes, this research, in some ways, also flattens our understanding of literature?

Editorial drawing by Vijay Nambisan, an Anglophone poet and journalist from the 1990s. From the Bombay Poets Archive at Cornell.

RK: I would say two things. On the one hand, the flattening is not coming from us. It’s not coming from the academic side so much as it’s coming from the market. The market perceives these phenomenon as flat. And the flatter it can get them, the more successful it is. I’ll give you an example; there was a New York times article talking about Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and she was told when she was trying to publish her first novel, Oh, it’s too bad that you’re not South Asian because then we would be able to sell it. I’m not joking. Why did a really great publisher say this to her? It seems if publishers can sell you in a package, that makes their job easier. That’s the market. We’re just describing it and we don’t necessarily have a lot of control over that.

The flip side of that is what are the risks of doing comparative work? And one of them is flattening. You will give preference to things that seem to show similarity and suppress things that show difference. Anyone who does comparative work is trying to balance that but it is, nonetheless, a risk of comparison. And it comes from both sides. But I would hope we can blame the market’s just a little bit more.

FB: Any ideas of where you see the next boom? And what might we do with that information?

RK: I think as my previous answer sort of gives away, it does seem to be that there is something like a boom emerging in Anglophone African literature. I say that in part because we have started to see breakaway stars, really big novels, and the preference of the Booker prize for Anglophone African fiction. Graham Huggin, for example, writes about the influence of the Booker prize on what he calls postcolonial fiction. But I think if he had written that essay five years after when he did publish it, he would have been talking about a South Asia specific phenomenon because that phenomena actually crystallizes after 2000 in the same way. Now we’re starting to wonder if the Booker prize is still as influential and we’re starting to see it push in a different direction.

We also see—in very inside baseball tersm—more growth in Anglophone-African specific jobs within the postcolonial sphere. In the American market, in particular, there isn’t always a sharp distinction between African American jobs and larger African diaspora jobs. Some scholars are doing great work in both of those spheres in a way that bridges the divide between them. But then also the academy can sometimes take one of those positions and put it into the other slot and then scholars reposition themselves to fill the need accordingly. Even though we might conceptualize those two fields as being quite distinct, other people do not necessarily conceptualize them with the same level of granularity and are willing to blur the lines a little. So for several reasons, that would be my guess about where we’re going to see a boom next.

FB: And what can we do with that insight?

RK: What do we do? That’s two different questions right there because I guess if you have a novel in your back pocket and you fit into this demographic, they’ll publish it. For everybody else, the advice is a little bit more subtle. I’m not sure what an individual can do to either perpetuate or retard a boom in progress. They ride the wave. I mean, sure, maybe we could try and ride the wave.

I guess the bigger question for us as scholars of South Asian literature is what’s next for our field? And there was a really interesting conversation about this at last year’s modern language association meeting where some of the language around “what’s going to happen to South Asian studies” was apocalyptic. I mean, really dark. “No one’s going to pay attention to us anymore.” “This other field is sucking away all of our resources.” Well, firstly, there’s a bit of entitlement there, right? Like a first child traumatized by the second child, but in a more serious way. The sister to this material is thinking about what we might learn from what in Latin American studies is called the “post-boom”. What happens after 71 or 73 or whatever you date the ending of the boom to Latin American literature? And the answer is a lot of really exciting stuff.

We see really interesting changes aesthetically in terms of what people want to write about. You have both the acceleration of very avantgarde kinds of writings. And then at the same time, this term towards authentic materials, different kinds of voices through the testimonial genre. At the same time you have these new opportunities in academia. The academics that were discussing this idea in MLA freaked out about real material things. “What’s going to happen to my nice job and the job that we were planning to open the line for next year”, or whatever. Well, what we learned from the Latin American cases is that actually the institutional roots of these booms endure after the boom itself is over. So the benefits to people studying South Asian literature, especially South Asian literature written in English, will continue to accrue because it’s actually harder to dismantle those institutions than it is to just stop buying new novels.

So we have the endurance of much larger Latin American studies architecture in U S institutions based on the exchanges that Latin American studies programs benefited from in the 1960’s. I think that will be true, to a certain extent also of the differently situated people who study South Asia and South Asian literature in particular.

FB: My last question is what kind of further reading can you recommend for people that are interested in either thinking about the relations between South Asia and Latin America, or simply representations of the market? What can we read to better understand the landscape of your research?

RK: I would say the one person who’s writing I would recommend in terms of opening up this very materially focused institutionally focused archivally backed type of investigation into literary markets is Deborah Cohn. Deborah Cohn has written both about the way that individual actors or curatorial functionaries have promoted booms in some of her earlier work. And then she’s written a lot about recently declassified information about the institutional push to fund booms from the U S government and its relationship to cold war politics. So if you’re interested in that political spirit and you want to see a great model for how that kind of investigation works, her book is the best and it has a really straightforward title, The Latin American Literary Boom and U.S. Nationalism during the Cold War.

The other trend that I would love to see more people participate in is the borrowing of conceptual models between fields. We have a little bit of this in Gayatri Gopinath’s Impossible Desires where she takes the term impossible from lo imposible, in the writing of José Rabasa writing about Zapatisatas in Exige lo imposible. So she uses a conceptual model that comes from Spanish and Latin America, and imports it into sexuality studies in South Asia, which I think is fascinating. That’s the kind of comparative work and the risk of crossing difference that it entails that, I think, really pays off. Same thing happens with Manishita Dass’ book, Outside the Lettered City, referencing La ciudad letrada by Ángel Rama. It’s about the rise of middle-class intellectuals and she takes that concept and uses it as a starting point to talk about the relationship of the middle class to lower classes and film watching habits. I would love to see more of that kind of work. I think that could be really powerful, even though, again, there are always risks to doing that kind of work; it requires a kind of generosity of reading practice on both sides, which I realize is a hard ask when we already are inundated with so many different categories that the postcolonial might contain, different types of reading lists that we’re meant to master etc. Nonetheless, a broader reading between these two fields at the level of theory could have benefits that we might not even be able to predict.

FB: That is one way to start. Thanks again for giving us your time and for letting us pick your brains about how to read between Latin American and South Asian writing.

RK: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Roanne Kantor’s book in progress is called Countershelf: South Asian Authors, Latin American Texts, and the Unexpected Journey to Global English

Leave A Comment