This essay was translated for MULOSIGE by Munir Fayyaz.

What is the Tradition of Urdu Literature?: “Urdu adab ki rivāyat kya hai?”

from Ādmi aur Insān

by Muhammad Hassan Askari (1919-1978)

Translated into English by Munir Fayyaz

To find the original essay in Urdu, please turn to pages 643-655 here.

_______________

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

The apparent circumstances tell us that poetry and literature are drawing closer towards their exodus from the world stage. People normally argue that it is very difficult for literature to stay in the presence of science and industry but we are witnessing a spectacle, that in Europe and America, thousands of young people are getting dismayed by science and industry and the ways of protest they have chalked out fall beyond the perimeter of literature and poetry. The type of literature some of them are using for attaining their goals is difficult to be taken as literature. This means there is something other than science and literature that has killed, or is gradually killing, literature and poetry.

There are still thousands of people and hundreds of scholars in the West who love and respect literature and consider literature an essential of human life. Indeed, the worth and value of civilization itself is prime reason behind this respect and they do not value anything above or beyond this. Such scholars should really feel concerned in such circumstances. These scholars express their concerns but do not probe reasonably into how and why these circumstances evolved.

Herbert Read. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

For example there is Herbert Read. He is a suitable example as he has been one of the greatest preachers of using modern arts in English literature after World War I. He has expressed a great dislike for the sort of literature and paintings which the youth of the day is creating. He is justified in his protest but he has not noted that the people whom he criticized vigorously can present the same canons in their defense that he has been preaching from for the last fifty years. This means he did not like the effects and causes created by his canons but he never doubted their validity. But the question is this that if emotion or instinct has to express them why is this form of expression destined to be in some form of art or literature in a predetermined style? Or what harm is ther if it has taken a certain form of expression? And it is also a good news if the scholars of the West predict decline or death of language as medium of expression. As it has become a trend in our society to seek biological explanation either it be society or civilization or religion and consider this explanation ultimate, therefore, Herbert Read explored that Art and Literature were rooted in Biology and Literature was a compulsory medium of human evolution but now the forces of evolution have discovered some alternative medium forsaking the older one. This leaves no excuse of rejection for the believers of evolution.

It also leaves no reason for retaining literature at least in Sociology, Psychology and Biology. But what to do of human obstinacy that in the words of Akbar Ilah Abadi demands:

Is par aray huey hain k goller ka phool lain

(They insist on getting wild-fig flower)

It is said that evolution is not just required but a very dear thing as well but man must maintain some sort of relation with his Past or his “Tradition”. This demand lacks reason but let’s accept it as a sentimental demand. Now it should be seen what Tradition is.

The case is perfectly clear in the East. Either they be the Hindus or the Muslims or the Buddhists, agree at two things. The first one is this that social tradition, literary tradition and religious tradition are not segregated apart but are the offshoots of a sole and great tradition which is the very foundation and the rest minor traditions are either its part or its derivatives. It is named Deen (religion) in Islamic jargon. It is obligatory to link with this tradition prior to joining any of the secondary and subordinate traditions. The second is that this tradition is derived from some divine or holy book then the representatives of this tradition translate it and this translation is taken as valid. And then there is a third thing which is a semantic constituent of the word ‘tradition’ in every language that it is passed on from one person to another.

But everything has gone the other way in the West. Firstly the concept of main and fundamental tradition has almost vanished from there. People there mention of social tradition, literary tradition and even sports tradition in such manner as they be distinct from each other and are able to function independently in their respective circles. If someone thought of it, he gave this niche to social tradition and subordinated religious tradition to it as a mere constituent. The Western people name this tradition as Culture. But if we reckon the existence of tradition within the social circle, there remains no need to found it on some divine or holy book. Tradition can mean trends, rituals and customs within the circumference of this definition. Trends keep on changing, so, why is it primarily necessary to keep a certain trend alive?

Photo by Nicola Fioravanti on Unsplash

A ritual can be good or bad like any other ritual. If it comes to emotional attachment with a certain ritual, emotional relevance is also not a permanent thing. Emotions can change ten times a day. Moreover, the permanent presence and acknowledgment of validating representatives is not necessary in customs. That is why in the circle of the Western literature we regularly and repeatedly witness this spectacle that a poet or style included in tradition by one is expelled by the other. It would be fine if the word tradition was used in the sense of trend. Some of the scholars went a step ahead ignoring the literal meaning of tradition altogether. They did not take the passing of tradition from one person to another necessary. M. C. Brad Burke, a famous literary scholar and critic, states that some poet initiated a ‘tradition’ by the end of 16th century that was followed for 20 years; another poet founded another ‘tradition’ that was conformed for 5 years; yet another poet devised another tradition that nobody followed.

This discussion concludes that the Western intelligentsia is very keen about keeping tradition alive and they are yet unable to tell what tradition really is. The biggest contender of tradition in English literature is T. S. Eliot. He claims that the continent has preserved all important ingredients of its tradition. He considers Dante the greatest poet of Christian tradition in literature who wrote a journal on the importance of composing poetry in local languages. At least the Western scholars regard it so and that is why this journal is considered to be of revolutionary scope. Dante said that the best of the poets were those who composed poetry in three languages and added a list of good poets along with. The West is very proud of its researches. The researchers did not bother to say that there was not a single poet in the list who composed poetry in three languages. A Muslim mystic pointed out that three languages here referred to something else. Did Eliot really know if tradition had been preserved in Europe?

Eliot is among few critics of the West who considered acquaintance with religion and theology compulsory for studying literature. But after mentioning it once he never revisited this idea elsewhere. He even recanted the book in which he made this statement. So it could not be understood what, according to him, was the relation between literature and religion. However, Jacques Maritain in France made an elaborate effort to derive literary principles from the theology of Thomas Aquinas. He says: “Cursed be I if I don’t follow Saint Thomas!” But the way Saint Thomas has been followed shows that he was misinterpreted because the trends coming in fashion in our times were reassigned by them to their patron.

But courage of the West is commendable. Despite all these complications the Western scholars persistently claim that they have such canons as the literature of every language and region can be assessed and comprehended with their help. The canons the West has devised during last three centuries have been discussed above in a nutshell. Now let’s have a look at the antiquity of the Continent.

Photo by Tbel Abuseridze on Unsplash

Many of the Western critics have claimed that fundamental theories regarding the start of literature were given by Plato and Aristotle that were only amended one way or the other in the later ages. Plato’s and Aristotle’s quintessential word is Mimesis. It was necessary to copy the real word the Greek word has been diversely translated (in Urdu). Some advocated that it meant imitation, some other contested that it meant portrayal, yet some other argued that it meant representation and some said it meant creation. Plato used this idea for rejecting poetry. That’s why it is not obligatory there to have the right sense of its meanings. But Aristotle used the same word for affirmation and acceptance, so, it requires the clarity of meaning here. It cannot be decided as every critic quotes from the Greek to validate his interpretation. Another way can be adopted. Plato rejects poetry because poetry cannot lead you to the truth. Aristotle accepts poetry because according to him poetry can lead to the truth. Now if we investigate what this truth is, we can decide whether it can be imitated, portrayed, represented, created or something else. To Aristotle and other Greek philosophers the greatest science was Metaphysics. If we consider its meaning, it refers to every truth that is beyond physical existence. But Aristotle also said that the most important branch of Metaphysics was Ontology, the science of being. He declared that both were synonymous to each other. It means that according to Aristotle, the Greek Philosophers and Christian philosophers the Middle Ages the Ultimate Truth was Being and their flight of wisdom ended here, no far and no further. Due to such flaws Mujaddad Alf e Saani (a great Muslim scholar and saint of 16th and 17th century) pronounced the Greek philosophy and theology as misleading and said that there hadn’t been any more ignorant clique than the Greek philosophers.

We can see how valid his proclamation is when we comprehend the Islamic concept of the Ultimate Truth. Hazrat Mujaddad states: “The essential self of the Omnipotent exists in His Self, not with His Being, and affirmation of the Self and application of the essential self is partially originated by the reason. ‘Allah is Supreme’ and as this affirmation of the self is a type of origination, extinction of the Nothing is also an origination. But when it comes to the Self, it can neither be related with ‘existence’ nor with ‘extinction’.” (Correspondences: Volume 3, 14)

How Self relates to the Ultimate Truth? He states: “The affirmed Self is a mere servant of His Ultimate Self and its Extinction is again a meager page of his court.” Obviously, such Truth can neither be imitated nor be portrayed, represented or created. It can only be slightly referred to.

When this is the Islamic concept of the Ultimate Truth and its duty is to make man get nearer to it, how can Aristotle’s literary theory help us in understanding in our poetry? Aristotle attempted to enthrone the page instead of the monarch. How can the rules be true for the page as they are for the monarch? The poetry composed within the paradigm of the Islamic canons ultimately has to refer to the Truth though the stages coming along the way to this Truth are also to be expressed in poetry. These stages are quad-natured: Nasut (the worldly), Jabrut (the ethereal), Malakut (the immense or the angelic), Laahut (the Divine). Greater poets will pass through all these stages, the minor will get lost somewhere in the middle. The same goes true for the first, the second and the third rate poets. (Here it would be apt to mention what Dante stated about composing poetry in three languages fundamentally related to these stages. He didn’t consider the poetry relating to the Nasut essential. Moreover, according to the researches by the Western scholars, Dante acquired this knowledge from Fatoohat e Makkiyah by Ibn e Arabi.)

Aristotle’s poetic theories do not take us any further from the stages of Jabrut or Malakut. We may call it imitation, portrayal or expression, all the same. We can only understand a small portion of the Islamic poetry with their help and that portion would not be characteristic of the finest poetry as well. You will find another difficulty that even a commonplace couplet would appear eager to fly away breaking the circle of being.

Daagh is dealt away with annotating him the poet of the hedonist. Have a look at his famous, rather notorious, couplet:

khoob parda hai k chilman say lagay baithay hain

saaf chuptay bhi nahin saamnay aatay bhi nahin

(Strange is the concealment in sitting abreast of the blind!

Not even hiding entirely, all the more so, neither revealing!)

Does it not hint the question of manifestation and concealment? It is said about Ameer Meenai that he entangled in adornment. He wrote:

wasl ho jaaye abhi hashr main kya rakha hai

aaj ki baat ko kyun kal pe utha rakha hai

(Let’s meet now, what of doomsday

Why defer today’s affair on tomorrow!)

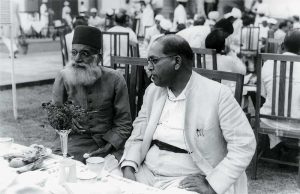

Ambedkar and Maulana Hasrat Mohani at Sardar Patel’s reception. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Does this couplet not indicate the phenomenon of witnessing God? Maulana Hasrat Mohani was in and out a religious person but under the very influence of English education categorized his poetry under the titles of the true, the romantic and the falsifying. The question is which category do these two couplets set in?

These two couplets affirm that as far as our traditional poetry is concerned, the Western poetic frame, however high it may be, is of no good use for us. Our traditional poetry is another thing, the West is failing even in understanding the poetry of its own middle ages. Some people even proclaimed out of frustration to exclude this age from literary history. Some of the honest and sensitive people proposed trying to understand this poetry with the help of Arabic poetry especially with the help of Ibn Al Faraz’s poetry. A couple of such attempts were made in France and surprising revelations were made by old Western civilization. But the poetry of Ibn Al Faraz can be fully understood by those who share his tradition, means share the same religion. But anyhow it marked a difference; some years ago the West commented that the Asian poetry had nothing but exaggeration and verbosity. This came in fashion here as well that even the valid critics started cursing our poetry. Even a temperate person like Haali wrote:

Hamaray qasaaid ka naapaak daftar

Afoonat main sandaas say jo hai badtar

(That dirty collection eulogies by us

Which stank more than a lavatory)

He didn’t think that the eulogies composed in the praise of aristocrats contained the elements of monotheistic faith. It turned out today that famous English poet Robert Graves commented after translating quatrains of Omer Khayyam that the West yet didn’t know what real poetry was. The Persian poetry is exceptional, even the Urdu poetry made some of the French readers exclaim that they now knew what real poetry was like.

But the awe of the English so took over late Haali and Shibli that they without having a primary acquaintance with the English literature only derived some stray ideas from 19th century English literature randomly and imprisoned their literature in these limited canons to ruin the literary understanding and taste of the succeeding generations. The worst damage they did was that they declared emotion the basis of poetry and purity of emotion its characteristic element. Secondly the chief end of poetry was set to be its prime purpose. These persons caused severe damage by promoting these principles not only to our literature but to our religion as well. They borrowed these canons from 19th century English criticism. In 19th century the Western people in general and the Protestant in particular had completely forgotten that the foundation religion is dogma, prayers and ethics succeed it. Dogmas have completely lost their importance in their eyes and Dogma* has become a swearing for them. Prayers are termed as rituals. Now the Protestants have left with only two things: ethics and emotion. So, some people started saying that the sole purpose of religion was to train people ethically. Some people opined that religion was the lightest of the tools available for satisfying human emotions. These canons were later implemented on literature and literary criticism that they became the most suitable for altering the religion and distorting the true understanding of it. Shibli, Haali and their contemporaries very naively considered these Western ideologies the quintessence of wisdom. This clear fact was altogether ignored that faith or human essence in Islam is not the name of some emotion or feeling but are acquired through the knowledge or nearness of the Omniscient. The place of wisdom in a Hadith is said to be the heart. The word “Ya’quloon” (deliberate) in the Quran appears with the “Qalb” (the heart). Therefore, the poetry that aids the perfection of faith is an expression of the omniscience, not emotions. Emotions, even physical approaches, might be brought into on a secondary level. Substituting omniscience with emotions would not only be a misapprehension but would also infidelity. And when it comes to what religious purity of intention is, it can be seen in the writings of Hazrat Thaanvi (Mualana Ashraf Ali Thaanvi) who has severally clearly distinguished between choice and chance of mind and body. As the truth of emotions cannot turn a taboo into a totem, in the same way it cannot turn a bad verse into a good one. Moreover, in mystic terms, emotion doesn’t stand for human passion; it refers to the pull of Divinity attracting man towards His Self. Then emphatically mentioning ethics and considering religion a mere tool for ethical training is also a modification in poetry and religion. It is essential to mention a delicate difference here stated by Mualan Thaanvi and many other mystics as well: the purpose of mysticism is rectification of heart and this is what mysticism is all about. The people who take self-purgation and rectification of synonymous commit a grave mistake. That’s why Mysticism and Psychology are also mistakenly considered analogous that should be avoided. The Greeks had the system of self-purgation but the 19th century Western scholars were even void of it but their ideologies were promulgated here in the name of national sympathy which was only for segregating poetry and religion. Religion might or might not have gotten damaged by it but our literary sensibility was ruined.

Now the question is that our educated class has also remained more related to literature than to religion; how did they let this literary sense ruin? Firstly, here, it was the incapacity of this class; the persons promoting the Western ideologies looked certified and that’s why they were niched to be the valid representatives of that stream of thought. Now the true representatives can be alleged for leaving the literature friendly people unattended. But in the 19th century our religious scholars were busy in their original and fundamental task i.e. in translating the religious knowledge into Urdu.

Then Mualan Thanvi’s explanation of the Ghazals of Hafiz (Sheerazi) and of Mathnavi of Mualana Rumi has been publishing periodically in different journals. His purpose was religious though anyone who wants to can extract complete education of poetry from these two books. For anyone who wants to get the quintessence of classical poetry, these two books are the only available resource for them. So, the people who deserved representing our tradition did not deprive a secondary thing like literature from it.

I was not like this that Hazrat Thaanvi considered the Urdu poetry unworthy of his attention. There appear several references in his writings that can be given the form of a book. We do not find such realistic references in elaborate essays of certified critics. A detailed discussion on this topic is not possible here, just an instance can be given.

It is said that people got aware of the importance of Momin as a poet when Nawaz Fatehpuri brought him to notice. But Hazrat Mualana had already stated that Momin was distinct among the poets of the Delhi school. In the same way he appreciated the poetry of Ameer Meenai as no critic could do. In context of meanings and subjects he lays particular stress on glee and gravity. For knowing the difference between them, have a look at this couplet of Ghalib:

Koi meray dil say poochhay t’ray teer e neem kash ko

Yeh khalish kahan say hoti jo jigar k paar hota

(O’ someone should ask my heart of your half-drawn arrow;

Where would this pricking have arisen had it pierced through the liver?)

Mualana Thaanvi told of the quality of this couplet that Ghalib only kept the apparent situation before him while composing this couplet and did not see the Truth, but in the Divine love, pricking increases with the increase in love. The Prophet (sallalla ho alay hi wasallam) Himself spoke that he held a greater love for Allah than the rest of His people and had a greater fear of Allah as well. This is about Ghalib’s glee. A couplet of Zuaq bearing the same subject is also found; look at the gravity:

Khudang e yaar meray dil say kis tarah niklay

Keh is kay saath hai aye Zuaq neri jaan lagi

(How come the arrow of my beloved be drawn from my bossom

As with it bonds my soul, O’ Zuaq!)

Have a look at three more couplets of Zuaq and watch for the glee and gravity that did not fall to Ghalib’s share:

Ta’amul kijeye zuaq e tapeedan daikhiye kya ho

Keh ab tak zib’h karnay ka nahin qatil ko dhab aaya

(be patient for a while, O’ my jactatoin, and watch what comes!

As my killer is yet void of the art of throat cutting.)

Hilaaye lab na behr e aafreen ham nay tah e khanjar

Keh qatil bad gumaan hai jaany apnay ji main kya samjhay

(I didn’t move my lips in praise under his knife

As the killer is ill at will and might take it otherwise.)

Teray dar say na aaya paas koi neem jaanon kay

Magar ronaa kabhi chupkay say ba’d az neem shab aaya

(None came near the dying at your hand

Only tears came to them after midnight)

The subject of Mansur recurs in the poetry of Ghalib:

Qatra apna bhi haqeeqat main hai darya laikin

Ham ko taqleed tunak zarfi e Mansur nahin

(The droplet of mine is also the river in its truth

I don’t permit Mansur-like shallowness)

Zuaq took this subject to where Ghalib was denied access:

Samajh yeh daar o rasan, taar o sozan aye Mansur

Keh chaak parda haqeeqat ka hain rafu kartay

(O’ Mansur, take these gallows and string as needle and thread

That help in sewing the torn veil of the Truth)s

In the same way the subject of drop and river is very dear to Ghalib but the grip that Zuaq had on its dimensions lack in Ghalib:

Kyun kar hibaab ho sakay darya e bay karaan

Darya say jab talak na milay toot phoot kay

(How come the water-bubble can transform into a vast river

Until it does not meet with the river after wrecking itself.)

Now look at one last couplet of Zuaq that will fully bring into light the fundamental flaw narrowness of the Western philosophers and will also tell of the universality of our literature. Zuaq has directly borrowed this subject from the Holy Quran which shows multifariousness:

Ahaatay say falak kay ham to kab kay

Nikal jaatay magar rasta na paaya

(from the borders of sky, we, since late

Might have escaped, but couldn’t find the path)

There is no room here for explaining these couplets but they can surely make one understand the meaning of the sentence by Mualana Thaanvi and this can also be known what the representatives of modern education have lost in terms of our tradition and civilization, and the Western literature is a child’s play when compared to it. But this is not an irreparable loss. Our religious tradition is still as alive as no other tradition in the world is. The people who continuously grieve at and care for “the Tradition of Urdu Literature” should explore the meanings of Tradition at first.

Chand khaani hikmat e yoonaaniyaan

Hikmat e eemaaniyaan ra ham bi’khaan

(Study less the wisdom of the Greek!

Study the wisdom of the believer, too!)

Leave A Comment