This essay was translated into English by Maryam Iraj as part of MULOSIGE’s Translations project. This project includes translations of essays of world literature from Urdu to English, as well as an our archive of translated Progressive and Modernist Urdu Poetry.

The Ancient Poetry of Korea: “Korea ki qadīm sha’irī”

“Korea ki qadīm sha’irī”

from Mashriq o Maghreb ke naghme (Songs of East and West)

by Meeraji/ Mohammad Sanaullah Dar (1912-1949)

.

Translated into English by Maryam Iraj

To find the original essay in Urdu, please turn to pages 521-541 here.

Note: It seems like Meeraji most likely familiarized himself with Korean poetry through the book The Orchid Door written by Joan Brigsby. You can find more information on Joan Brisby here. In 1929 Brigsby also published Lanterns by the Lake (through the Trubner).You can find a free online copy of Brigsby’s (1932) version here.

Seoraksan, Inje-gun. Photo by Alexandre Chambon on Unsplash

Since the beginning of this world, man has always been in a state of unceasing migration either individually or socially. The decision of leaving one’s birthplace, one’s homeland, is a very serious step; yet it is compelled by human curiosity, evolving human needs and the pressing claims of the times. When the Aryans left Central Asia and settled in the West, few lost touch with their roots or succumbed to the lures of surreal Indian magic after crossing the Himalayas. Ultimately, they laid the foundations of several unique and unmatched traditions and civilizations both in India and in the Western world. Nevertheless, there is another example like this in history which bears the same pattern as the Aryan migration. Exasperated by overpopulation, Koreans were driven to migrate to China to inhabit its vast lands. They left their homeland but the paleness of their land always stayed with them, and the qualities of their inherent culture also remained intact. Chinese people thus spread elements of ancient Korean traditions throughout their land too. Like any other culture, Chinese poetry was also reflective of its own values and traditions. Although many examples of Chinese poetry have been enfolded into Indian culture too, we will focus solely on Korean poetry for the moment.

In the early centuries of the Christian calendar, in Korea or “land of tranquil mornings”, the acquisition of knowledge was an affair taken with great pride and privilege. Regardless of their humble beginnings, educated people were preferred over the elites for positions in political offices. Nonetheless, and barring a few exceptions, poets who ventured into politics always failed. Interestingly and ironically, the best of Korean poetry was penned down in exile by such failed politicians.

Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash.

In the year 957AD, Gwageo was a national civil service examination and poetry was a quintessential and constitutive portion of this examination. Anyone who claimed to be intelligent had to excel in this examination to ascertain and validate their intellectual authority. It was, however, no easy undertaking to pass this examination. It required a great deal of hard work, dedication, and focus. It was mandatory to pass the Gwageo examinations within the span of two to three years and in four stages. The final examination always took place in the palace of the emperor. Those who appeared in the final stage were the lucky ones as most candidates were sifted out in the initial three stages and, resultantly, doomed to obscurity. It was the crowning desire of every candidate to pen poetry in the presence of the emperor. Those who aced the prestigious Gwageo examination were awarded membership into Hanlin—an imperial academy. Or, in the fashion of Korean literary jargon, we could say that successful examinees “wandered into the wilderness of literary aesthetics” to rise higher and higher.

The daily humdrum of Korean life was inundated with literature, even a common man had a verse ready for every occasion. And so, versifying became a custom of that age. In the remains of ancient Korean poetry that we have available, there is a famous poem written by Shah Poori in 17th Century BC. It narrates the story of a young queen who left the palace following a disagreement with the elder queen (or first wife of the King). The king ran after the young queen to reconcile, but his efforts failed. Two birds who were perched on the branch of a tree caught the attention of the dejected and bereaved king as he was on his way back to the palace. His poetic sensibility was stimulated and as his creative juices started flowing, he composed the following song:

Photo by Tanjir Ahmed Chowdhury on Unsplash.

Song

On golden paths, in yellow beams of lights

I am standing all alone and unattended!

All this glory belongs to me—these rice fields,

This golden path!

It all belongs to me, is all mine!

But there is one thing that I cannot attain

The one for whom my heart is longing

And here, in this tree, two yellow birds love each other

But why do they sing with such exhilaration?

———————

Traces of Chinese ideas can be easily seen in Korean poetry. During the Tang dynasty, these impressions were much more prominent and obvious. Chinese poems were famous to the extent that many Koreans thought of these as part of their own culture. Moreover, literature produced in Korea was also deeply influenced by Chinese literature. Despite this, we can nonetheless perceive a distinct effect of the Korean national spirit in Korean writing.

Korea’s geographical situation impacted its earliest literature. Korea is an isolated island and modes of communication and trade were naturally difficult to carry out with ease. Hence, maintaining good communication with neighboring countries was very challenging. Despite this problem of travel, we find many travelling poems in Korean literature and they represent a very pleasant side of the corpus. Vivacious observation was a salient literary feature of this poetry. An example of such poetry is a poem written by Yi Chung-kwi in 1554 AD.

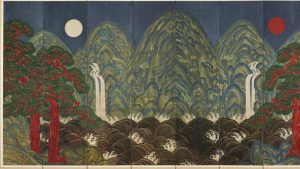

Image source: https://www.neh.gov/humanities

An example of this caravanserai,

On the banks of the river!

These tall yellow trees on the shores,

This air of sugarcane fields!

These blue and ever tender clouds rising to the morning sky

Wearying away the elegant clouds bit by bit

And here the evening is cloaked in a pennant of sadness!

Stretched all over—

On the top of the mountain!

On the day of the voyage, it all appeared in the creases of my face,

But I don’t know,

That a moment is added to my peace

In my mind, there is nothing more than whittles

Shining on the banks!

And these songs of mine are the fountain of dreams!”

——————-

Since the poets of those ancient times cherished the position of scholars, their poetry lacked romantic emotions. For Korean poets, the theme of love between men and women was both, aesthetically and emotionally, considered unacceptable. Because sexual drive was considered much like any other drive such as hunger or thirst, there was no poetic or romantic attraction left in it for these poets. These poems document long discussions although our own literary tastes would be vexed by this, as we are not attuned to such long narratives. Political satires were written too but the discourse embedded in these pieces were of no use for a wider readership. Despite having a strong presence in Korean literary convention, these satires offer little interest for readers who bear fine literary taste or hail from different cultures.

Korean poetry can be broadly categorized in three sections:

- Philosophical (or thought-provoking) poetry

- Poetry meant for friends (including laments and elegies)

- Satirical poems

But even of these satirical poems, very few can retain their true charm once translated. A poem by Yi-I is offered as an example. This poet was counted as a celebrity poet of his times, though his poetic output was very limited

Thinking Through the Modern Times

Thinking Through the Modern Times

A candle burns, is it fire or a flaming marble,

Comb runs through my hair

Parting on one side, parting on the other

My head is lighter than ever

Scattered on the ground is my dead hair!

Freshened them up, vivacious, tied them up again

Wish, we could comb our country like this,

To bid farewell to greed and foolery

Yes, this is the way to oust the half-dead corpse of thought from the heart

And to beget new powers to beat the enemies

Waning candle finally dies…dies

Goes silent, the shivering marble flame

Drowning all the wishes in sleep

—————————-

In philosophical Korean poetry, the most important and prevalent symbol is that of the moon. This symbol has entertained the Korean heart for centuries. With every passing day, new symbols and similes were devised to connote the moon. At times, it was described as a “torch of pain”, “month of the sky” or, at times, a “big dry fruit”. When one thing, the moon, has so many different names, it brings immense complexity to the task of translation.

The moonlight in Korea is immaculate and pure; it has the magic ability to transform a simple village into a marble-like valley. The following song was written by Choi Choong in the early 2nd century. He was a serious, pious man and wrote the following song to be sung accompanied by a string instrument (Sarode) and drum.

Jeong, Song, Gyeomjae Yangcheon Isujeong (18th c.) Source: Wikimedia Commons

Light of the silvery torch

Light——Devoid of the lament of the rose

From the seventh apron of deep slumber

Led me with signals to this place!

A shadow of Juniper all over my walls

And on my venetian blind

Casting a shadow of mounting desire!

And my life in house is nothing more than a shade!

Devoid of awakening,

And sleep also fades!

There is music building in this profound silence!

Is it the sound of sad wind rustling through Junipers?

Or is it the melody of a song,

Attuned to a secret instrument.

—————————–

Korean civilization reached its pinnacle of perfection in the 6th and 8th century AD. Then, gradually, it began to decline. It was the time of universal brotherhood among men which left a deep impact on the literature of its time. It was a common practice for two young men to prepare for a government examination together. Towards the end of their preparation, the bond of comradery between two men could be strengthened to the extent that the two took “Oath of the Peach Garden”. This was the oath of eternal companionship for life and, even, beyond the confines of life. With this bond, the rarest form of literature blossomed in Korea. Mutual encouragement and a compassionate, constructive criticism raised the bar of Korean Literature. Elegies were written for the deceased friends and, usually, these pieces proved to be literary masterpieces. To substantiate this, we quote the elegy of Yi Soong-in, written in 1400 A.D. for reference:

Lament for a Friend

(1)

My heart bursting with pain,

The sound of the cricket in rain

Glad and pleased,

Remind me of your laughter

(2)

Eyes brimming with tears,

The vail of this crimson morning

And on this immaculate mountain

Hangs your golden robe

With the hues of red and green

(3)

My abode is occupied with pain

And the voices haunting my house

Mock me

For a wishful dream of my heart!

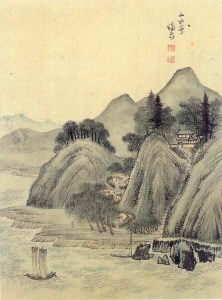

An Kyŏn: Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Land, 1447. Source: Britannica.com

An example of scholarly companionship and fraternity can be seen in the libraries where these students and scholars assembled to debate and discuss books and to seek knowledge. The ideas on literary and religious matters that were developed here continued to influence Korean thought for many centuries to come.

Translating foreign poetry from verse to verse is an uphill task and almost impossible, if one intents to capture the style and intrinsic poetic qualities of an individual poet. However, based on a few examples, we can make this claim: a more subtle and a profound poetic output was produced by those poets who preferred isolation and lived secluded lives. The thematic sublimity in their poems is of a superior quality than the poems written by court poets. This distinction can be further stressed with the following two poems written in 12th century A.D. One poem is written by Kwak Yu who was a successful businessman in his time. He entered the field of politics because of his extraordinary scholarship and, despite being a poet, he succeed in it. His friend, Yi Chah Yun, was also a rising star around the same time when he became recluse. After thirty years, Kwak Yu, went to meet his friend. Both friends wrote poems about this meeting as part of a custom.

The first poem here is by Kwak Yu:

Near and Far

Near and Far

In the mountain skies,

Meeting after a long time, today,

We both—were one soul in our youthful days—one soul!

We toiled in the moonlight—toiled,

Together, we did…

Until dawn breaks, and gone is the queen of the night!

But, now, we are torn asunder by the days gone,

Yes, when you looked away!

From the threshold of the garden!

Where every leafage calls you back in vain,

When you returned? —you never did

Only, the flying heron across vast heavens,

And fragments of clouds,

Covering your head

You kept treading the path without ever looking back, incessantly!

These hours of dawn and dusk were your robes

And the moon-wine was at your disposal

Enjoy the silvery wine!

Now, I look at you and recoil,

My lips are sealed!

Wondering, how our souls will be merged, once again?

In the above-mentioned poem, we can easily recognize the usage of multiple poetic devices. For example, in this poem the garden does not simply connotate a place filled with flowers but also a place filled with females. Hence, the poet is ironically mocking his friend for being an ascetic. He is suggesting that his friend has shunned the world over no other reason than a woman. The usage of these kind of similes, metaphors and other poetic devices was a conventional practice in those times, and it was obligatory to learn tis craft. In order to gain a thorough understanding of the poetic imagination, it necessary to learn each of these similes, metaphors, and idioms and their corresponding ideas. Accordingly, this diction and these poetic devices are inadvertently stimulated during the reading process.

The use of double-entendres, and other literary devices that convey duals meanings was a common practice in Japanese poetry. But among Korean poets the usage of such literary devices and techniques was quite rare. The previous poem is one such rare example though we find the usage of such literary devices in abundance in Kwak-Yu’s poem. For example, a “heron flying across vast heavens” and “fragments of clouds” not only convey the scenic beauty along a journey but also refer to particular spiritual and intellectual themes associated with these metaphors, as if their usage can take us to new soaring heights through their association to ideals of eternity.

In response to this poem, Yi Chah Yun wrote a poem titled “Meeting with a Friend in Solitude”. Though it is a very long poem and all of it cannot be quoted here, a few excerpts have been provided for reference below. Select verses appear to be complete poems in themselves and communicate the genuine feeling that these poet-friends nurtured for each other.

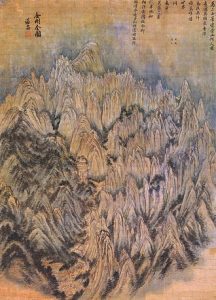

General View of Mt. Geumgang by Jeong Seon. Wikimedia Commons.

Meeting a Friend in Solitude

Night—yes, last night, it was the autumn moon,

And the farewell flight was obvious!

Today, your arrival is expected,

As if the spring returns,

“Till it was my companion of seclusion,

Left was my lonely being with your memories,”

Used to ask the moon,

To steal a few glimpses of yours through a window,

So that when it returns to this mountain,

And I finally get the tidings of you!

Alas! The moon held on to the heaven,

For never to reach, to return, or to reveal,

And when I was lost in memories,

I only consoled myself with the thought of your return

When you are done with your engagements, my friend!

“Come, and take off your turban,

Let loose your hair!

And the air will purge you of the trivialities of the world!

Now, rest on this astute bed

With a satiated heart in your side!

And I don’t claim of the silence of the Juniper trees,

Neither they talk in subtle whispers!

Nor they conspire in their hearts!

Guardian of the stars does not quiver to search for your flaw!

And no dagger is cloaked in the clouds!

There are two similes which have been used in the beginning. For example, “farewell flight” clearly gestures to the flight of the hero while the arrival of spring (spring returns) refers to the happiness which will be transpired upon the much-awaited reunion. Other than these examples, the style of the poet reads very simply and aligns with his own simple lifestyle.

To conclude our narrative of these poets, we shall quote a poem of the poet, Yi Whang, who came three centuries later in 1550 AD. He wrote the following poem in veneration of his spiritual guide Yi Chahyun.

In Memory of My Guru

In Memory of My Guru

These hazel clouds in the twilight across the vast expense of heavens

When collected, they form a jungle!

And the river swings by!

And continues to flow in silence, to the west!

And, so do I continue with a throbbing heart!

On the same path he once treaded in elegance!

My mentor, resided here once, in the same streets!

Ploughing the land, he lived in these fields!

And the one who drowns in the memory of such sages!

Time fades to be erased, and one is reminisced!

As moon lights up the heaven!

His soul was also a treasure of light!

His existence was like a fortress on the top of the hill!

Soaring higher and higher, devoid of depravity!

Eternal lament of the silent mountains!

Companion for this soul!

Who never yearned for this world!

Shallow was every worldly affair, “for him”!

This poem was written when the poet visited the mountain where his spiritual guide once lived. Following these two great universally popular poets, another great poet was born after thirty years whose name was Yi Kyu Bo. He was at once a scholar, a poet, and a politician. Different studies suggest that this poet held some very fine qualities. He spent his early life fighting abject poverty, starved himself in the pursuit of knowledge, and never deviated from this noble path which was his aim as long as he lived. Ever since his early days of youth, he was resolutely trained his mind to understand the transience and triviality of worldly things. He was candid and forthright both in his speech and in his writing. Naturally, this earned him many enemies. This straightforwardness proved to be a hindrance in his progress yet, despite the opposition and resistance, he kept walking his path with fearlessness and persistence. After passing the civil examination, he secured a position in the court but was soon forced into exile for one year. After one year, he was reinstated in his position. However, in comparison with his spiritual and intellectual growth, his worldly achievements and progress bear little significance for the reader. His life was a perpetual burning flame. Music and poetry were his real passions, and he drew sublime power from these two to sustain his peace of mind. His poetry was both individual and subjective, and the presence of a wide array of thematic variety in his poetry continues to startle us. His best poems are generally long but, here, are three short poems:

Arrival of the Morning

A crow busy in cawing in his nest on the river shores,

I know dawn is about to break,

Sight of the full moon turns pale!

These dark waves in grace,

As if clouds crossing the moon!

And morning wind sings!

This very abode…,

Where a few trees swing in curves

In the deep silence, from far away… far, far away….

A song is wandering towards me, with an immaculate speed

Moving towards me gradually, it becomes,

From closer to closest!

Every fisherman of night is returning to his abode!

Bright robes, like flowers!

Like these glowing rays of the moon!

As if both are one!

Either these are the spirits or humans, I am not aware!

But, gradually, their songs efface!

————————

The title of this second poem is “Departure”. We also find a note alongside this poem which reads, “On the last day of the third moon, the poet imagines he is bearing witness to the departure of the spring god.”

Lee Oi-Cheong. Creative Commons.

Departure

Among flowers, a bed made of fallen leaves,

Festive god of the spring sleeps on it!

Moon has been hazed in the sky, towards the end of the night,

But God is fast asleep, inebriated?

At once, he fell in his sleep, as if

A fragrant flower brings the dew closer to him!

When away, he woke up from the sleep smiling

And left his moist, fragrant bed?

Intoxicated with the fragrant flower, enamored,

In search of love, wandering in every direction, lonely!

Who would be a companion of his inner storms, now?

May be, he would profess his love to the garden of peaches!

But this playfulness of love has worn him out!

Would he fall for apricots now?

Or ferocity of this does not excite him either!

But, the robe of a flower trembles,

Shines, or a moth flutter!

And there is tremor born in the red tree!

And the spring god wakes up!

And become the companion of our intimate affair!

This flower, superior to all those in heavens?

These are the wee hours; moon is fading fast!

Morning flames are on the verge, farewell of moon is near!

A voice of distant footsteps reaching from forlorn land!

Morning prevails, and the garden dries!

Melody of the tears continue to resonates in my ear!

——————–

This third poem is a narration and reflects the unique mind of the poet Yi Kyu Bo; in a traditional country like Korea, girls held little status while boys were regarded as important, especially by their fathers. Here is a translated poem,

Death of a Little Girl

My young girl with a shining-snow like white face,

My backyard is so quiet now,

Once, her colourful attires were seen among these beautiful flowers,

She started talking sweetly at the age of two,

And, at the age of three, she was a sweet, shy, and a well-behaved girl,

This year, she would have been four; and must have learned to hold the pen.

I could have taught her how to read and write!

But she went away, and only the pen left!

My young, little bird residing in my nest!

Why you flew away?

Just came and disappeared, like a thunderclap!

I have learnt to be in the memory of days past, in silence,

I can spend these days in anguish,

But who would dry the tears of a mother?

Signs of an upcoming storm are hitting the fields.

And many ears of the wheat will be lost in the gust of stormy winds!

Farmer never reaps how much he sows-

———————

Other than Yi Kyu Bo, another Korean poet of the 14th century who wrote on common life and topics was Yi Soong-in. His poem “Autumn Song” is a good example of his poetry. This poem exudes intense conflict, and the style continued to be famous for many years to come in Korean literary circles.

Photo by Daniel Kim on Unsplash

Leaves fly in the whirlwind across the orchard yard—

Last year, it was the sound of the dancing steps,

This year, a melody of crying tears haunts me,

This red and white shadow of the tree, casting its image in the water, —

Last year, this heart was the heart of a happy poet,

But, this year, warrior’s blood is the force to reckon with!

————————–

Another poet of sixteenth century Korea, Yi-I, was known as an ascetic among his people. From this century onwards, scholarly classes did not have the respect that they had held in former years. It was a changing time, and the decline of ancient literary values was on its way. Here follows a poem:

In Response to the Hardships of My Country

Today, before these three months

Today, before these three months

I soothed my heart

“Will be spent on the moon,

this pang of separation of yours,”

These visiting springs

And the dried, withered leaves,

Green, once again

Flowers blossom, and blossom with smile,

A new moon appears in the heavens!

The rain of monsoon Encircling the entire world!

Falling from mountain The waterfall roars!

And for an instance,

Rainfall breathed and fell silent,

Frogs croaked in the garden,

Stream of tears fell from eyes,

And the monsoon rain starts again!

——————

As mentioned earlier, love poems are very rare to find among ancient Korean poets. However, we still find a few love poems which deserve our attention. All such poetry was written by courtesans, mistresses or nautch girls. Hence, their names and identities were not known and have been be consigned to oblivion. Although these songs cannot be held at par with the highest standards of Korean poetry, they nonetheless have a distinct lure. An example is given below:

Deception

Many a times, I dreamed,

Dreams of your retracing steps!

But woke up to find-

It was a knock of the rain on my window-curtains,

And, on the tree branches!

Attuned to such bearings, and scared,

While I wait, and silently,

You breeze in as the mist of the monsoon!

—————–

There was a gradual decline in ancient Korean poetry. Signs of this revolution appear in the beginning of the nineteenth-century. As soon as foreigners arrived and Western culture made inroads into the country, some intrinsic Korean cultural realities gradually faded away and finally died. Scholarship lost its significance in national life.

With passing time, the difference between the old and the new grew larger. Old Korean ways became a distant memory. A new modern Korean man replaced that old scholar who held close to his heart the philosophy of Confucius, whose dreams were frequented by scholars and poets. And this new Korean man took centerstage, replacing the graceful scholar of the past. Hence, there is an ever-increasing intellectual gap between the old and new.

Where does Korean literature stands today and what will be its position be in future? We cannot say anything with guarantee. Nonetheless, with its brilliant disposition and with an inherent streak to attend to the prevalent themes intact, and with religious trends alive and in place; we can claim with certainty that the objective of every Korean poet is to progress and soar higher than ever before.

Leave A Comment