Itzea Goikolea-Amiano is a Post-Doctoral Fellow working on the Multilingual Locals, Significant Geographies (MULOSIGE) project.

The Journals Al-Motamid and Ketama

Al-Motamid was named after the eleventh-century ruler of the kingdom of Seville in al-Andalus, Muḥammad Ibn ‘Abbād al-Mu‘tamid.

Northern Morocco has tended to be cast as a provincial hub in scholarship about Morocco and colonial Maghreb because it fell under the tutelage of a minor colonial power such as Spain – unlike the rest of the country, which by and large became a French Protectorate, or an international zone, such as the nearby city of Tangiers. However, the literary journals Al-Motamid (1947-56) and Ketama (1953-59) made visible and enabled the circulation of contemporary Arabic poetry between the Arabic-speaking Middle East, the Maghreb and the Mahjar (Arab American diaspora); and of contemporary poetry between Arabic, Spanish, and other European languages.

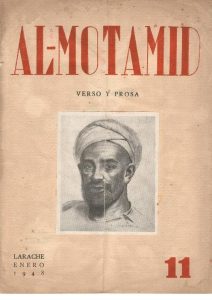

Al-Motamid. Verso y Prosa was founded by the poet Trina Mercader (Alicante 1919 – Granada 1984) and named after the eleventh-century poet and ruler of the kingdom of Seville in al-Andalus, Muḥammad Ibn ‘Abbād al-Mu‘tamid. Al-Motamid saw the light in the coastal town of Larache in 1947, and in 1953 it moved to Tetouan, the capital of the Spanish Protectorate, where it ceased publication in 1956, the year in which Morocco became an independent nation.

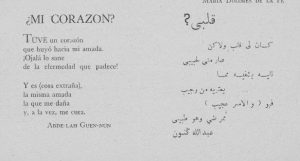

A poem (“My heart?”) by ‘Abd Allah Guennoun. Originally written in Arabic, the poem was translated into Spanish and both versions were published in Al-Motamid 20, issued in April 1950.

Ketama was founded in 1953 in Tetouan by the poet Jacinto López Gorjé (Alicante 1925 – Madrid 2008), and bore the name of the northern Moroccan Riff area in north-eastern Morocco and the village where López Gorjé had worked as a teacher in the early 1950s. The journal it continued publication until 1959. Unlike Al-Motamid, Ketama was bilingual from the very beginning.

Scholars such as Abderrahman Tenkoul (1988) and Tarik Sabry (2012) have long urged for the inclusion of journals as sources for literary and intellectual history – a genre and medium that is so far underrepresented in the fields of Moroccan, Maghrebi and world literature. What Al-Motamid and Ketama accomplished in the late 1940s and early 1950s was certainly unusual and unprecedented in many respects, though because of their location their enterprise has largely gone unnoticed in the genealogy of modern Arabic and Moroccan literary histories.

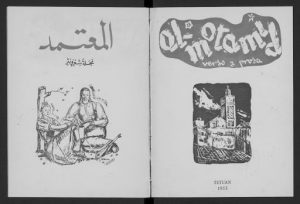

Al-Motamid became increasingly bilingual after moving to the capital Tetouan in 1953. That same year, Ketama saw the light in Tetouan. Before moving to Tetouan, all the content in Al-Motamid was arranged from left to right. After 1953, the formal organising principle became language, and both journals were divided into two main linguistically-determined sections: an Arabic one, from right to left, and a Spanish one, from left to right. They also formalised the double cover on equal terms. As a result, the status of the Arabic language was raised and the Arabic section of the journal acquired its own personality, agenda, and cultural identity, particularly due to the efforts of Muhammad al-Sabbagh.

First double cover in Spanish and Arabic. Al-Motamid 25. Source: Spanish National Library.

Besides Moroccan and Arab authors’ influence on the Spanish editors, the increasing weight that the Arabic language acquired in the Spanish Protectorate especially since the late 1930s is linked to the discourse of Spanish exceptionalism which the authorities under General Francisco Franco constructed, and which crystallized in the so-called “Hispano-Arab culture”. This discourse, like the “Hispano-Moroccan brotherhood”, was also a means to weaken the hegemony of France (see De Madariaga, Aixelà-Cabré, Mateo-Dieste, Calderwood).

Bilingual cover of Ketama.

Occasionally trilingual sections were published, with Italian or French poems translated into both Arabic and Spanish. A few poems were also translated from Catalan and Valencian – languages and cultural identities which were repressed by the Francoist regime in Spain –into Arabic. At the same time, not all the Moroccan collaborators wrote in Arabic. Indeed, Al-Motamid and Ketama constituted important platforms for the first generation of Moroccans who wrote in Spanish, the so-called “builders” (Rekab 1997) or “founders” (Limami 2007) of Hispanophone Moroccan literature, such as the Rifian Muhammad ‘Abd al-Salam al-Timsamani and the Tetouani ‘Abd al-Latif al-Khatib in these journals.

Literature and other texts in Al-Motamid and Ketama

The collaboration between Spanish, Moroccan and other Middle Eastern and American diasporic authors made these two “minor” bilingual journals small but significant world literary nodes. The journals made visible and enabled in the circulation of contemporary Arabic poetry between the Arabic-speaking Middle East, the Maghreb and the Mahjar (Arab American diasporic) literary worlds; and of contemporary literature between Arabic, Spanish, and other European languages. They also enabled the reorientation of some Spanish orientalists from al-Andalus and Andalusi literature towards contemporary Arabic literary production.

Poetry, the genre cultivated by the three most engaged and prolific writers of the journals – Mercader, López Gorjé and al-Sabbagh– was privileged in both journals, though they also published prose, essays, and short stories.

The selected texts (below) are grouped thematically, and the original and translated versions are made available. They have been translated into English by Jack Clift. You can also read more about his translation strategies here.