Jack Clift is a doctoral researcher and translator affiliated with the Multilingual Locals, Significant Geographies (MULOSIGE) project.

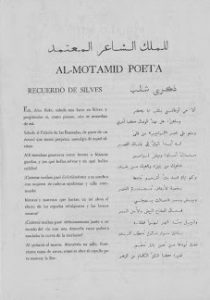

Recuerdo de Silves / Dhikrā Shilb

Al-Motamid 5, Larache 1947. Source: Spanish National Library.

Translation from Arabic

Memory of Silves

Oh, Abu Bakr, will you not greet the places I dwelt in Silves

And ask them: is the promise of our time together as I remember it?

Give salutations to the Palace of Windows from a young man

Who always longs for that very palace.

Those abodes of lions and of women, light and tender,

Their groves so lush, their quarters so grand.

How many nights I spent there, taking delight, in their shadow,

From well-fed haunches and from slender hips;

Women, light and dark, moving my very soul

With the touch of light flanks and dark barbs.

The night I spent in pleasure at the side of the river

With a woman, her bracelet like the curved path of the full moon,

Removing her clothes to reveal the rich, radiant branch

Of a willow, opening like the bud of a flower.

.

Translation from Spanish

Memory of Silves

Oh, Abu Bakr, greet the hearths where I dwelt in Silves and ask them if, as I expect, they still remember me.

Greet the Palace of Balconies on behalf of a young man who forever feels a longing for that same citadel.

There reside warriors like lions alongside pale gazelles – and in what beautiful woods, in what beautiful dens they reside!

How many nights I spent in its shadow, finding joy with women of sumptuous hips and slender waists:

Women, light and dark, who produced in my soul the effect of radiant swords and dark spears!

How many nights I spent, with such delight, in the bend of the river with a young woman, whose bracelet was like the curve of the current!

Removing her cloak, she revealed her waist, a flowering branch of willow, just as the bud opens to display its flower.

.

Commentary

Dhikrā Shilb (Memory of Silves) is attributed to al-Mu’tamid bin Abbad, the namesake of the Al-Motamid journal and the third and final ruler of the ṭāʾifa of Seville before its conquest by the Almoravids in 1091. Al-Mu’tamid’s father, al-Mu’tadid, had conquered the independent ṭāʾifa of Silves in 1063, incorporating it into the larger ṭāʾifa of Seville. The ‘Abu Bakr’ to which this poem is addressed is likely Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Ammar, referred to as Abenámar in Spanish sources, who was a close confidant of and, later, wazīr to al-Mu’tamid in Seville and himself a noted poet; after being made governor of Murcia, he turned against al-Mu’tamid but was subsequently captured and put to death (see here and here for easily-accessible accounts of his life). Al-Mu’tamid’s poem here looks back on an earlier, happier period of his life, before he was exiled to Morocco by the Almoravids.

While we have quite a lot of information on al-Mu’tamid, the author of the Arabic poem, we do not have so much as a name for the author of the Spanish translation included here [1]. What is formally quite a traditional Arabic-language poem becomes, in its Spanish translation, a prose poem in free verse; the terseness of the Arabic source is, therefore, loosened slightly in the Spanish translation, giving the translator some latitude to bulk up the Arabic. Concomitantly, there are a few important discrepancies between the two poems. Most noticeable, perhaps, is the difference between the allusion to the ‘curved path of the full moon [through the sky]’ in the penultimate line of the Arabic (munʿaṭaf al-badr) and the ‘curve of the current’ (curva de la corriente) in the Spanish. These imply quite different reference points (moon/river), which in turn evoke different images: the brightness of the moon and the intangible flow of the river, the latter of which is less effective in conjuring the gleam of the (presumably metal) bracelet.

But it is the allusion to ‘gazelles’ in the third stanza of the Spanish poem that is, I think, more problematic and is likely a misunderstanding or gloss of the Arabic on the part of the Spanish translator. In the first hemistich of the third line, the Arabic calls the Palace of Windows the ‘abode’ of both ‘lions’ and of ‘white’ or ‘light-skinned’ people (bīḍ) who are ‘soft’ or ‘tender’ (nawaʿim, plural of nāʿim or nāʿimah); this contrast between animals and humans is carried forward in the second hemistich of this line, where the poet refers to the ‘thickets’ or ‘groves’ (ghīl) of trees, the home of the lions, and the ‘quarters’ or ‘rooms’ (khidr), where the people reside. Where ‘gazelles’ and their ‘dens’ come into this, as they do in the Spanish, is anyone’s guess. But this gloss has a profound impact on the imagery that the Arabic poet develops in subsequent lines. In line four of the Arabic, the poet mentions savouring ‘well-fed haunches’ (mukhṣabat al-ardāf, literally ‘fertilised’ or ‘well-watered haunches’) and ‘slender hips’ (mukhdabat al-khaṣr, literally ‘sterile’ or ‘arid hips’). The image created here is a double one: of the poet feasting, in the darkness, on different cuts of meat, variously ‘plump’ and ‘lean,’ but also enjoying, sensually, the stereotypical ‘hourglass’ figure of a woman (‘small’ hips, ‘large’ buttocks or ‘haunches’). It is exclusively this latter description – of women with ‘sumptuous hips and slender waists’ – that finds its way into the Spanish translation. We therefore lose much of the word-play, which, in the Arabic, helps us to understand the third line in a new light: the lions are, here, both the wild animals that the palace grounds house and, metaphorically, the men who are allowed to ‘prey’ on women for sexual gratification.

These ideas of sexual union are altogether more prominent in the Arabic poem, which in its first line alludes to the ‘promise of time together’ (ʿahd al-wiṣāl), using terms that evoke more explicitly the coming together of lovers. (This is glossed much more generically in the Spanish as the poet’s hope that the ‘hearths’ of Silves will ‘remember’ him.) Yet the idea that the love the poet expresses is for a woman/women is initially much more vague in the Arabic poem than in the Spanish: while the Spanish translator has the narrator note his enjoyment of ‘women’ (mujeres) in stanza four, the Arabic poet alludes only tangentially to the gender of his lover(s) in line five, using generic plural nouns (bīḍ and sumr, ‘light-skinned’ and ‘dark-skinned’ people) with an explicitly feminine plural active participle (fāʿilāt); this becomes more specific in the final two lines of the poem, where he specifically mentions ‘a woman [with] a bracelet’ (bi-dhāt siwar) who ‘takes off her clothes’ (naḍat burdahā). This is, I would venture, more in-keeping with the traditional ambiguity of Arabic and broader Islamicate romantic poetry, where the gender of the ‘beloved’ is often left open to interpretation.

One final note on the ‘palace’ or ‘castle’ to which the poets refer in line/stanza two. The ‘Palace of Windows’ (qaṣr al-sarājīb) to which the Arabic poet alludes does not seem to exist in Silves in a recognisable form anymore, but, as this unattributed blog post notes, was apparently built by al-Mu’tamid while he was governor of Silves under his father. Sarājīb here is evidently a variant of sharājīb (from sharjab, ‘window’), an Andalusi word that has entered Moroccan darija. The Palacio de las barandas to which the Spanish translator refers has a slightly different meaning, with baranda usually referring to a ‘banister’ or a ‘balustrade’ that surrounds a balcony or similar [2].

Leave A Comment