Jack Clift is a doctoral researcher and translator affiliated with the Multilingual Locals, Significant Geographies (MULOSIGE) project.

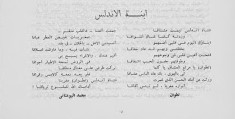

Mohammed al-Bu’annani – Ibnat al-Andalus / Hija de al-Andalus

Translation Arabic > English

Al-Motamid 26, Tetouan 1953. Source: Spanish National Library.

Daughter of al-Andalus

Oh, daughter of al-Andalus, you captivated a desirous man,

And the more he sang to you the more ardent you made his desire.

Today I embrace your sons in my heart

And in their presence my beating heart pounds once more.

Al-Motamid 26, Tetouan 1953. Source: Spanish National Library.

You have opened the eyes of my heart to look upon their faces

And my loving eyelids have encircled them with tenderness.

Oh, Tetouan, you pasture of lovers, the object of my words

Of desire – it is through you that ordinary people turn into lovers.

From your mother you inherited such beauty, the glow of which

Floods Morocco – and you did not forget lands further away, too!

My heart was broken, yet you forged my bonds of intimacy

With alluring women, from whom lingering perfume flows.

With these lovers, you made me forget my own people in the place I grew up –

And it was not for want of anything that I left there in the first place. [1]

It is in you that I reside, temptation floating around me

In the fields upon which the birds generously bestow their chorus.

I let my eye pass freely over the satisfaction you provide

And it has never since been bathed in its own tears, as it was before.

Oh, daughter of al-Andalus, Tetouan of our Morocco,

May God preserve you, an antidote for those who have been bitten!

.

Translation Spanish > English

Daughter of al-Andalus

.

Oh, daughter of al-Andalus, you captivated a man who loved you

And you made his love for you grow, as he sang of your beauty!

.

With both hands I hold memories of you in my heart,

For it is because of them that it beats.

.

You opened its eyes with your lessons,

Which now rest in the orbits of my love.

.

Oh, Tetouan, city of lovers,

It is because of you that I speak of love;

It is because of you that human beings live in love.

.

From your mother you inherited a beauty

That flooded all of Morocco

And the entire universe.

.

Though my heart was split, you bound me together

With young men who, even today, exude their perfume.

.

With these friends, you made me forget my family,

Those who live in the city where I was born,

Those who I would never abandon, not even in the search of gold.

.

I live in you and the wings of my mind

Rise up with the birds’ song.

.

Let my eyes cry, while I sing to you,

Even though my tears do not fall as they once did.

.

Oh, daughter of al-Andalus, Tetouan of our Morocco,

May God make you last forever,

For there must always be an antidote for someone who has been poisoned!

.

Commentary

While Mohammad al-Bu’annani is clearly noted as the author of the Arabic poem, it is not clear whether he translated this into Spanish himself or whether Mohammad Ibn Azzuz Hakim – credited, in tiny type, at the bottom of the page of three Spanish poems in which Hija de al-Andalus is included – was responsible for this translation. Whatever the case, noticeable immediately here are the different forms that these poems take: while the Arabic poem follows the traditional Arabic pattern of lines of two hemistichs (the final hemistich culminating in the repeated rhyme –ā), the Spanish poem is written in free verse and fluctuates between couplets and three-line verses. The content of these lines or divisions remains, however, broadly the same in spite of these formal differences, albeit with different linguistic plays and images employed in the two languages.

The final hemistich of the Arabic poem, for example, describes Tetouan as the ‘antidote’ (tiryāq) for those who have been ‘bitten’ or ‘stung’ (malsūʿ); the double meanings of each of these words alludes to the poet being ‘burnt’ (in a romantic sense) and taking to alcohol to numb the pain (a resonance that is absent in the Spanish, where the antiquated and quite specific word teriaca, ‘theriaca,’ which itself mirrors the Arabic term, is used). By contrast, the Spanish poem plays on the double meaning of órbitas – as both the ‘orbit’ of one object around another and, therefore, the realm in which the poet’s love is felt and, simultaneously, the ‘orbits’ or ‘orbital cavities’ (‘eye sockets’) with which he views his love. This is absent in the Arabic, which mentions the ‘eyelids’ (jufūn) of the poet specifically.

Perhaps most striking in terms of content, however, is the difference between the forms of love that the poems present. While the Spanish poem notes the poet’s love for Tetouan, the ‘daughter of al-Andalus,’ he remains attracted to the city because of the platonic friends he makes there (muchachos, amigos). The Arabic poem, by contrast, is much more explicit that the poet enjoys the romantic liaisons he finds in the city and that the city is a place of ‘desire’ in a more erotic sense: the words he uses to describe ‘lovers’ (ʿushshāq) and ‘love’ (hawā) as well as the ‘alluring women’ (mughriyyāt) and his own ‘lovers’ (khullān) all point to this (although the latter can, admittedly, also be a word for ‘friend’ as well as ‘lover’). This, I think, ultimately brings the Arabic poem more into line with broader poetic conventions in Arabic, which privilege romantic love (requited or otherwise), often with an unnamed or unknown ‘beloved.’

Leave A Comment