Rana Haddad grew up in Latakia in Syria, moved to the UK as a teenager, and read English Literature at Cambridge University. She lived in London and worked as a journalist for the BBC, Channel 4, and other broadcasters. Rana has also published poetry and is currently mostly based in Athens. The Unexpected Love Objects of Dunya Noor, her first novel, was shortlisted for the Polari First Book Prize and selected as MTV Arabia Book of the Month. She is now working on a novel that will be set in London which will portray England in a way it has never been portrayed before.

How Love is Revolution: The Unexpected Love Objects of Dunya Noor

by Rana Haddad

The Unexpected Love Objects of Dunya Noor is a vivid and satirical novel. It captures life in Syria at the end of the last century, when a moustachioed military dictator named Hafez al-Assad ruled Syria. It’s also a playful yet profound coming-of-age narrative about Dunya Noor, a curly haired anti-establishment young photographer who does all the things a girl like her is not supposed to do and whose curious spirit and rebellious heart are pitted against her society’s expectations.

Rana Haddad and Itzea Goikolea-Amiano had a conversation about The Unexpected Love Objects of Dunya Noor (you can watch the webinar here!). Here Rana writes a more detailed account of how and why love is the most underrated form of resistance in a rigid authoritarian social and political system.

Book cover: The Unexpected Love Objects of Dunya Noor

The protagonist of the novel, Dunya Noor, is considered a ‘rebel’ or exceedingly annoying and revolutionary not because she has taken up weapons against her own society, family or country, but because she has the insolence to pursue her own interests which arise from her own heart’s desires. Such a pursuit requires one to be able to know what one loves and be able to fight for it, be it her camera (her art) or Hilal or some other revolutionary Love Object, which readers will discover in the book.

The other characters in the book whom I would categorize under the sub-heading ‘revolutionary’ in their choice of Love Objects are Suha Habibi, the singer, and Hilal Shihab, the astronomer, both of whom are mavericks. They swim against the tide in a society that forbids too strong an expression of individuality and offers each child and adult a list of instructions dictating to them exactly what to do, what not to do, and how to think, how not to think; a society where you must serve others not yourself, and where wrong is never righted and right is considered a sort of crime, where on certain occasions even romantic love can be considered a crime if it’s in disobedience to the wishes of your family, and particularly your father.

Dunya is a child, then a young woman, who does what she wants to do rather than what others want her to do. This alone makes her a terrifying person to those around her, especially her father Dr Joseph Noor, who feels that authority over her should by rights be in his hands and that something is wrong in a world where this isn’t the case, causing him either to scream or to threaten to have a heart attack. Ironically, Joseph is a heart surgeon and many of his clients are fathers suffering that same predicament with their unruly daughters.

When I think of the word ‘revolution’ I see an image of a wheel revolving or turning, each turn is one revolution – turning the world as we know it or wish it to be on its head. When the world as we wish it to be is at a diametrical opposite to how those who have power over us would wish it to be, we need courage to turn the wheel, and in this novel I show how Dunya in particular does that, although she is not the only one – other characters also play a role in this subtle and not so subtle revolution.

Why is Love or the ability to pursue one’s own desires and think one’s own thoughts such a threat to the established order?

Perhaps it is because if you follow your heart too much and in a consistent manner, as Dunya does, the results are unpredictable, and often unexpected. In this novel I test out the theory that your heart knows more than you do and has plans to take you on a journey that is often the opposite of what your society or family might want for you, so instead of continuing to repeat what your forefathers and mothers did, you may (gasp) innovate and discover new territory, discover who you are separately from them, before re-joining them on their journey, a journey which has beauty in it, although it is often flawed, but which through fear and rigidity they cannot envision changing. That is why the young who want change must be sacrificed on the altar of power and a distorted meaning of the word ‘tradition’.

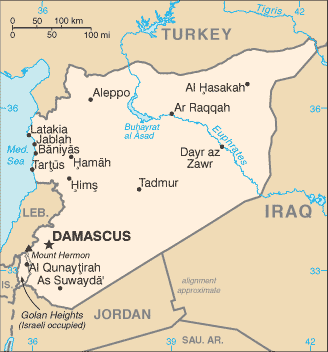

Map of Syria, Wikimedia Commons.

In a rigid totalitarian system small acts can cause disruption, even mayhem otherwise known as revolution. Dunya does very small things, or says small things, or makes particular choices, most of which would be seen as perfectly harmless in some other society, but in Syria during the 1970s to 1990s such small rebellions were regarded as beyond the pale! This is where both the humour and plot twists often derive from in this novel.

A character or person such as Dunya whether in real life or in fiction, a young girl in a large country like Syria, could be regarded as a Nobody. How could a nobody have any clout or cause a revolution? And so it is with someone like Hilal, a working class young man from Aleppo, the son of tailors, or Suha, the daughter of a baker.

Yes, in society’s eyes all three characters and those like them are perfect nobodys! Yet they do have the power to use the two-letter word NO, to cause a revolution. Even in Arabic the word No is composed of two letters (لا). If one of them or two or three or more of them dare to say No, they must have courage and be capable of dealing with disapproval, resistance, ridicule, and possible punishment, but by holding on to that word No whether quietly or loudly, secretly or openly, they can and do create a revolution, a disruption of the social order.

In George Orwell’s 1984 love is banned while in Brave New World it is trivialized, in the Middle East the wrong sort of love is often criminalized mostly by families rather than the state, families who want their off-spring to marry into the right sort of families, with the right lineage, class and/or religion, and if the child disobeys sometimes the punishment is very harsh, and the price for such love is high. We are talking here about heterosexual love. When it comes to other types of forbidden love, let’s not go there!

Love is the ultimate disruptor – Why?

Because it causes you to love across hierarchies and divides that are essential to holding up the status quo – which thrives on division – us vs. them. The same instrument used for love is also used for Hate: The Heart. You must be careful how to use it.

Everyone wants to own your heart, and they do not want you to use it for yourself. Even a dictator such as Hafez Al-Assad is determined that the hearts and minds and even souls of his subjects must be his property, not their own. I am thinking here of the famous chant that Syrians were expected to shout out during Pro-Assad marches: “With my soul and my blood I sacrifice myself for you oh Hafez (later his son Bashar)”.

In fact love can be a double-edged sword, and your ability or propensity to love can be a means to either being enslaved, or to freeing yourself.

It is a skill to learn how to use your heart and not let it be used.

Love and forgiveness are also revolutionary in the spiritual sense, especially in high-conflict societies where conflict serves power structures, and divide-to-rule is a technique that has been used by tyrants and emperors since time began. So if you love against those false divides, you are fighting against tyrannies, remember that!

Only listen to your heart. Do not believe the hype!

If your source of information is your parents, a political leader, the newspaper, television, prophets, priests, you are in grave danger of being manipulated and taken for a wild ride or on a most unpleasant goose chase.

This is dramatised in my novel in the way in which Suha Habibi’s parents lost her – it was because they did not listen to their hearts, and instead listened to ‘expert’ advice, from a coffee-cup reader.

The heart is the most powerful instrument and this is what my book is all about. You don’t need a machine gun, but you need the courage to obey your own heart, and in order to do so you will often be forced to disobey outside influences, people with more power than you, people who can punish you.

Leave A Comment