Jack Clift is a doctoral researcher and translator affiliated with the Multilingual Locals, Significant Geographies (MULOSIGE) project.

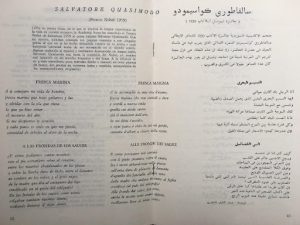

‘Fresca marina’ / ‘Al-Nasīm al-Baḥrī,’ Salvatore Quasimodo

Spanish introduction

Ketama 13-14, Tetouan December 1959. Source Fundación Jorge Guillén (2011)

The Swedish Academy has awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1959 to the Italian poet Salvatore Quasimodo, ‘for his lyrical poetry, in which the tragic experience of life in our time finds expression.’ It is for this very reason that Ketama is devoting its central pages to this unique poet, who has not been duly acknowledged in his homeland and whose universal standing has only just come to be recognised in the wider world. Rarely translated into Spanish and completely unknown in the Arabic language, Salvatore Quasimodo was, until the awarding of the Nobel Prize, a name who was almost ignored in the Spanish-speaking world and in the world of Islam. Ketama therefore hopes to contribute to the spread of his poetry by making available in these pages of honour two poems in Arabic and Spanish, accompanied by their respective originals.

Arabic introduction

The Swedish Academy has awarded the Literature Prize in 1959 to the Italian poet Salvatore Quasimodo for his lyrical poetry, in which the tragedy of life in our current age finds expression. This magazine is without doubt the first to translate any of his output into Arabic; before he won this prize, this poet was unknown in the East and in the West.

English translation from Arabic translation

Sea Breeze

As a man I compare my life to you,

Oh gentle sea breeze, carrying seashells and light.

You forget, with the wave that approaches,

The wave whose reverberation provoked the movement of the wind.

I listen to you whenever you wake me

And in each moment of calm between the clash of the waves there is a clear sky,

Its calm like the calm of the trees in the clearness of the night.

English translation from Spanish translation

Sea Breeze

To you I compare my life as a man,

Sea breeze; you bring pebbles and light

And you forget, with the coming wave,

The wave that had only just made

The movement of the air resound.

If ever you wake me, I listen to you

And every pause is a sky in which I lose myself,

A calmness of trees in the clarity of night.

Commentary

Though short, there are a number of striking differences in these two translations of Salvatore Quasimodo’s Fresca marina. The Arabic translation in some ways makes more explicit what is left unsaid in the Spanish translation: ‘the wave’ that causes the air to move is named directly in Abd al-Latif al-Khatib’s Arabic translation, whereas there is a slight ambiguity in the Spanish translation as to what causes the sound of the wind (olvidas con la ola que viene / la que ya hizo sonar, literally ‘that which’ but more likely here ‘the one which,’ alluding to a previous wave). But the Arabic translation also uses its directness to its advantage. The repetition in the final two lines of words from the same root that convey calm (hādi՚ah, hudū՚’) serves to emphasise the disjuncture between the clash of the waves and the quiet gaps between them. These differing levels of linguistic detail are reflected in the opening lines of these translations, too: whereas the (unnamed?) Spanish translator begins the poem with an allusion to the intangible, ever-changing wind (a ti, a mirroring of Quasimodo’s a te), al-Khatib centres the human narrator of the poem (anā al-rajul), a shift that perhaps reflects the ‘firmer’ quality of the Arabic translation, which paints a more specific, grounded picture of a man reflecting on the repeating cycles of life. We see this, too, in the allusions to being woken by the wind. There is a conditionality to the Spanish translation (si, ‘if [ever]’) that is made habitual in the Arabic (kullamā, ‘whenever’), reflecting a lived experience rather than a possibility.

Leave A Comment