Jack Clift is a doctoral researcher and translator affiliated with the Multilingual Locals, Significant Geographies (MULOSIGE) project.

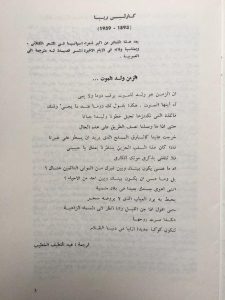

‘El temps, fill de la mort’ / ‘Al-Zaman walad al-mawt,’ Carles Riba

Spanish introduction

Carles Riba, a Spanish poet in the Catalan language and one of the greatest masters of Spanish poetry in the twentieth century, is another of the great Spanish-speaking lyrical poets who have disappeared in 1959. To pay homage to his memory, Ketama is also publishing, with the Catalan original, the Spanish and Arabic versions of one of his poems.

Arabic introduction

This poet is considered one of the greatest of Spain’s poets in the field of Catalan poetry and, to commemorate his passing in recent days, we are publishing one of his poems translated into Arabic.

English translation from Arabic translation

Ketama 13-14, Tetouan December 1959. Source, Fundación Jorge Guillén (2011).

Time, Son of Death

Time is a son of Death, always watching, never faltering.

Oh, Death, this is what he always says to you when your time comes!

The pleasure that we hoard makes our steps slow and cowardly

Until we reach the middle of our journey

And you come upon us like an armed thief who wants to steal every good thing of ours.

If it is this sad state of dispossession that awaits us after you are gone, my love,

Then do not burden my thoughts with the memory of your death.

Ketama 13-14, Tetouan December 1959. Source, Fundación Jorge Guillén (2011).

What, then, would distinguish you from the others who have died and are sleeping?

Or, yet – what would distinguish you from any other living person?

I long for your body to be faraway in some forgotten land

Embraced by the chill of an absence that even magic could not tame

So that I might say, as night falls and I look to the bright sky,

‘This is how her soul passed on

And became a new, eternal star in a world of darkness.’

English translation from Spanish translation

Time, Son of Death

Time, son of Death, watches and never tires.

Oh, Death, this is what he always says when your time has come!

The joy that we treasure makes us walk our path like cowards;

And then, halfway through our journey, you come at us,

An armed thief, as if you would take for yourself every good thing of ours.

If I am to face this sad deprivation second,

My love, then do not weigh down, dead, on my thoughts:

What would distinguish you from the other dead people who are there?

(And what distinguishes you, now, from any of those who live around me?)

I want your body, faraway in a forgotten land:

A chill of absence that no spell could conquer.

And at night I will say, looking up at the glowing sky:

‘This is how her spirit came

To be a new, eternal star over the dark world.’

Commentary

Striking in these two translations of Carles Riba’s El temps, fill de la mort is how similar many of the terminological choices are. Lines 10-14 in both R. S. Torroella’s Spanish translation and Abd al-Latif al-Khatib’s Arabic translation reflect each other reasonably closely and, in line 5, both translators make use of similar double meanings to continue the metaphor of the ‘joy’/’pleasure’ we amass or cherish in life being ‘stolen’ from us at the time of death: both Torroella’s use of bien and al-Khatib’s use of khayr draw on the fact that these words can simultaneously mean ‘good’ or ‘good things’ and tangible ‘goods,’ ‘wealth’ or ‘property.’ What differs most substantively are the formal and/or punctuation choices. Torroella’s Spanish translation mirrors the stanza division and punctuation of Riba’s source text closely, while al-Khatib’s Arabic translation omits almost all punctuation and collapses the three stanzas into one. This has a pronounced impact on the lines (lines 6-9) that make up the second stanza in Torroella’s translation. In the Spanish, the connection between the (anticipated?) death of the beloved and the existential questions this raises for the narrator is made clear through the colon; the brackets, moreover, hint at a growing sense of dread or unease when the poet thinks about what death means for his ‘living’ relationships. This is altogether more disjointed in the Arabic (although it is possible to connect afkārī, ‘my thoughts,’ in line 6 with the questions that immediately follow it); this makes these questions seem a little bit more general and less connected to the loss of the beloved that the poet seems to be mourning preemptively.

Leave A Comment