Jack Clift is a doctoral researcher and translator affiliated with the Multilingual Locals, Significant Geographies (MULOSIGE) project.

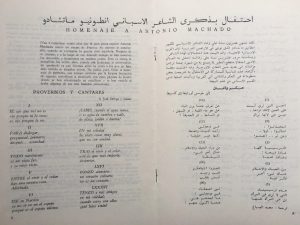

Machado, Proverbios y cantares / Ḥikam wa aghāni

–––

Translation from Spanish

Tribute to Antonio Machado

Ketama 12, Tetouan 1958. Source Fundación Jorge Guillén (2011).

It will soon be twenty years since the great Spanish poet Antonio Machado died on French soil. His destiny led him there, just as the Spanish Civil War was coming to an end [1]. After his death, and throughout the intervening period of time, there have been memorials and tributes in many countries. But it is now, on the twentieth anniversary of his death, that this tribute is being paid universally, for there is at present scarcely a single language left on earth into which his exceptional poetry has not been translated. It would be remiss, then, not to have a tribute from Ketama, a tribute which, though modest because of the limitations imposed by space, contributes to the commemoration of Machado with these pages of honour, where some of his most well-known Proverbs in Spanish have been selected and where these have been translated into Arabic.

–––

Translation from Arabic

Commemoration of the Spanish Poet Antonio Machado

It has almost been twenty years since the death of the great Spanish poet Antonio Machado, who died on French soil during the Spanish Civil War. There have already been many commemorations of this poet and now, on the twentieth anniversary of his death, the literary world has organised unprecedented commemorations in his honour because of the fame that he has enjoyed since the translation of his writings into a number of European languages. The Ketama journal has taken advantage of this occasion to participate in the commemorations of Machado: some of the poems from the Proverbs and Songs collection have been translated into Arabic and, to make their source clear, they have also been included in the Spanish section of this journal.

–––

Commentary

English translations of Antonio Machado’s Proverbios y cantares (Proverbs and Songs, 1912-1924) are widely available online; see the two parts provided by Armand F. Baker here (#1-#47) and here (#48-#99) [2]. Given their existing availability, we have decided not to translate the Spanish poems into English here; and, given the brevity of the poems and the closeness with which the Arabic translator, Mohammed Sabbagh, appears to have rendered them, we have decided that a translation of the Arabic translations into English is not necessary or worthwhile here, either [3]. Sabbagh has followed the Spanish very tightly in his Arabic translations and the themes and ideas that the poems touch upon – the blurred line between reality and irreality, between certainty and uncertainty, and the tension between loneliness and social interaction, for example – are all generally maintained across the two bodies of work.

One difference does stand out in the final poem (#86), however. In the Spanish, Machado writes that he has friends ‘in his solitude’ (en mi soledad), a sentiment mirrored in Sabbagh’s translation (fī waḥdatī). Yet the ordering of the phrases that follow shifts the focus slightly in the two poems. ‘When I am with them’ (cuando estoy con ellos), Machado writes, ‘how far away they are!’ (¡qué lejos están!) – phrasing that emphasises the friends’ distance from him, as the initial subject of the sentence (and the stanza). Sabbagh’s translation reads differently: ‘how far they are from me / when I am with them!’ (mā abʿadahum ʿannī / ʿindamā akūn maʿahum). The stress here seems to be on the poet’s distance from his friends, rather than how distant they are from him – a subtle shift, to be sure, but one that opens up a space for questioning who might be to ‘blame’ for this distance, physical or otherwise, which itself has implications, for instance, when it comes to the discussion of ‘narcissism’ (al-narsīsiyya) as an ‘old’ and ‘ugly’ habit in poem #3.

Another important difference between the Spanish and Arabic included on these pages comes in the introductory paragraphs that accompany the poems. The general thrust of these paragraphs is the same: the twentieth anniversary of Machado’s death has attracted particular attention and Ketama wishes to participate in the commemorations by publishing a selection of the poet’s work. But it is interesting to note the different ways the Spanish and the Arabic quantify the fame that Machado has accrued posthumously: while the Spanish notes that there is ‘scarcely a single language left on earth’ (no quedando ya casi idiomas sobre la tierra) into which Machado’s poetry has not been translated, the Arabic specifies much more clearly that his renown is based on his writings being translated ‘into a number of European languages’ (ilá ʿadīd min al-lughāt al-ūrubīyya). Implicit, here, are the different scales within which a Spanish-speaking and Arabic-speaking reader of Ketama might conceptualise Machado’s work: the Spanish-speaking reader might rest assured that Machado’s poems have already been translated into all the ‘world’ languages of importance, and that these Arabic translations are something of a ‘bonus,’ whereas the Arabic-speaking reader will have it confirmed to them that these translations are an explicit move away from the European focus on Machado and his work.

Leave A Comment